Portrait of Yakama Indian Lokout adds to history of brother Qualchan

From 1907 to 1930, Seattle photographer Edward Curtis released 20 volumes of “The North American Indian,” a project that comprised 1,500 photographs of American Indians from tribes across the country.

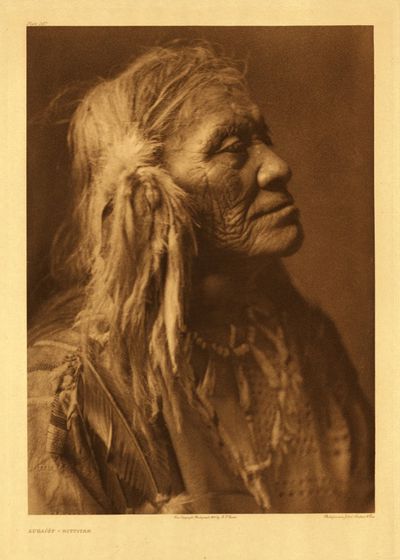

In the seventh volume of that collection is a portrait of Luqaiot, a son of Owhi – chief of the Salishan band that lived in the Kittitas Valley.

A recently made identification reveals that the 1910 Curtis field photo immortalized the man also known as the Yakama warrior Lokout, who outlived his doomed brother Qualchan by 56 years.

The name of Qualchan is familiar to Spokane area residents, but it recalls an unhappy chapter in the region’s history. The name of the Yakama chieftain who died in 1858 has been taken by a golf course, a housing development and a foot race. His brutal hanging gave the name to Hangman Creek (known locally as Latah Creek).

Qualchan’s brother Lokout, like him, was a guerilla fighter. Both men defended their homeland against miners and U.S. military might. But Lokout’s life in crucial ways is more inspiring than his brother’s, particularly for his capacity to survive.

In 1856, Lokout was fighting against Gov. Isaac Stevens following a second Walla Walla treaty meeting, where Stevens affronted local tribes by coercing them to sign away their traditional lands. The Nez Perce and Yakama were firing at full gallop, the less seasoned white troops dismounting to take aim. The cover was scrubby and sparse.

Qualchan, leading the charge, ordered his people to set the prairie burning and keep on fighting after dark. At age 22, Lokout was practiced as a tracker, sharpshooter and guide, but the Walla Walla battle on Sept. 19, 1856, almost did him in.

According to numerous accounts, Lokout sustained two shots to his chest but fought on. He killed one trooper in hand-to-hand combat before keeling over, passing out from fatigue and pain. Night fell and the skirmishing continued. Grass fires set by his tribesmen smoked and flamed.

A passing trooper spotted Lokout on the ground and swung near enough to smash him in the forehead with his gun butt, caving in his skull. Militiamen often delivered such strikes to save lead when they ran low, intending them as surefire deathblows.

The hardy Yakama warrior did not die, though. He healed from the crushed forehead and lived until 1912. “His skull had a hole in it that would hold an egg,” wrote rancher, legislator and historian A.J. Splawn, who interviewed Lokout in 1906. Photographic evidence from Lokout’s adoptive Spokane Tribe confirms the astounding gouge.

Four years after Splawn met the disfigured Lokout, Curtis and his entourage made a visit. Curtis was compiling interviews and photos for the seventh volume of “The North American Indian,” to focus on the Yakama of Washington and the Kootenai of Idaho.

How Curtis heard about Lokout is impossible to say, but Qualchan’s mutilated half-brother agreed to be interviewed and have his photo taken. The resulting image shows the former Yakama warrior in aristocratic profile. His face is lined, his chin nobly raised, necklace and feathers belying his 76 years of age. The entire photo is tinted gold in the signature Curtis orotone, or “Curt-tone.”

What is remarkable about that photo, though, is less what it shows than what it hides – the brow gouge, the forehead furrow that remained as a memento of the so-called Yakima War of 1855-58. Using a forehead comb-over, Curtis styled Lokout’s hair to hide the gouge. Curtis may have considered the wound too unsettling to behold, too graphic a record of the man’s capacity to withstand the white invaders.

Some ethnologists and historians fault Curtis for manipulating his images. He portrays his Indian subjects in stereotypical ways, they say, typifying them as a vanishing race unable to endure the modernist onslaught. He also makes noble savages of them.

In one shot Curtis erased a clock that blighted a teepee scene. And always he turned his gaze away from cars that hauled his gear to reservation grounds; the squalor some tribes had to live amid; and from the factory clothing they acquired in trade.

Curtis traveled with quaint regalia to ornament his subjects, to fit them with popular notions of the times. He likely imported the gear to adorn Lokout in the photo – the necklace and the feathers a kind of costume jewelry for character actors on a stage.

Tribal photos show Lokout dressed like other Indians of the time – in blankets, leggings, hair braids, even a cowboy hat with rattlesnake-skin band. He probably earned a dollar in exchange for sitting for the shot, the standard rate the photographer paid.

If no one before now has connected the history of Lokout and his sibling Qualchan with the Curtis photo, it’s because Curtis spelled the names “Luqaiot” and “Qahlchun.” Field linguists often transcribed Indian names phonetically or relied on other erratic sources.

To confound history even more, Lokout went by several other names – Loolowcan, Laquoit, L’Quoit, Quo-to-we-not, Soka-tal-ko, and Rain Falling from a Passing Cloud. Some Indians took different names at different periods in their lives, or gave fake names to whites who might do them harm. Had Col. George Wright not known the name of his brother, the ill-fated Qualchan might have lived as long as Lokout did.

Due to the surface charm of the Curtis shot of Lokout, it took on a life of its own after its 1911 publication. It came to be colorized and altered, bundled as a 1930s trading card with chewing gum sold by a company in Boston. The tilt of the chin became pugnacious or defiant. The forehead laid bare became whole.

Lokout was present when Latah Creek became Hangman. Wright’s hanging of Lokout’s brother and others on its banks changed the name, on federal maps at least, from Ned Whauld Creek and Latah Creek. Historians still debate how exactly Qualchan came to be so hoodwinked there and the roles his kinsfolk played.

The day Qualchan died, his wife, Mary – also known as Whist-alks or Walks-in-a-Dress – and father Owhi were likewise in Wright’s camp. The hanging heralded the end of the so-called Yakima War. How and why did one of the savviest fighters in Eastern Washington ride into that camp and die within a quarter-hour?

By the time Curtis encountered Lokout, the aging warrior was the only Indian survivor of that day. In a lengthy interview Curtis conducted to accompany his photograph, Lokout shared 17 pages of memories, including those of that deadly morning on Hangman Creek.

It was May 1858, nearly two years after Lokout sustained his disfiguring injury against Gov. Stevens’ troops. Wright was punishing the Yakama, Palouse, Spokane and Coeur d’Alene tribes after they overwhelmed and defeated Lt. Col. Edward Steptoe at the Battle of Pine Creek. In one story of Qualchan’s hanging, Wright lured Chief Owhi to his camp and chained him. In another, Spokane Garry betrayed them. In yet another story, Wright “sent word to Qualchan that if he did not surrender, Wright would hang his father. The next day Qualchan appeared carrying a white flag,” as regional historian David Wilma wrote at historylink.org. “He wore Yakama finery of beaded buckskin and he rode his best horse. His wife carried his rifle and his brother Lokout accompanied them.”

That last version makes it appear as if Qualchan, Lokout and Whist-alks had offered to make a truce or surrender. The account that Lokout gave Curtis 52 years later, though, contradicts that version. Lokout reported that an Indian who was working for Wright met them on a trail. Their father, the Indian said, was relaxing in Wright’s camp and having a friendly visit. He offered to guide them. The turncoat’s story seemed reasonable, because Lokout’s father had “treated” with Wright previously.

Some historians say Qualchan resisted, others that he pled for his life, still others that he gave up bravely. Lokout and Whist-alks knew their lives were on the line. How they escaped remains most controversial of all. Some allege that Whist-alks grabbed a saber and slashed her way out. Others report that Wright released her, whereupon she plunged a war lance to the ground and left it quivering in defiance.

In his old age, Lokout told Curtis his own account of that day, which appears in the book. His brother had been taken away. Lokout, seized by soldiers and bound at the hands and neck, feared that he was facing the ultimate punishment. An Indian in Wright’s camp, though, lied on his behalf, claiming that Lokout was a member of the Spokane Tribe. And so it seems, from the records issued by Curtis, that one liar betrayed Qualchan into Wright’s hands before another liar saved Lokout’s life.

Learning that Qualchan was hanged, and Owhi later shot dead trying to escape, Lokout fled to Flathead and Blackfeet country. The widowed Whist-alks joined him. He had been such an active combatant in the war that he knew Wright would try to hunt him down. They stayed away for a couple of decades. Northwest Indian resistance to the white invaders faded. Confined lives on the reservations began.

Eventually Lokout wed Whist-alks. Perhaps to conceal his Yakama identity, he enrolled in the Spokane Tribe – of which both his mother and wife were members – and changed his name to L’Quoit. Curtis inadvertently concealed Lokout’s identity, and confounded historians in the process, by recording his name as Luqaiot. Whist-alks died in 1909 and Lokout outlived her by three years.