Former governor Gardner, 76, dies

Environment, education, social services his focus

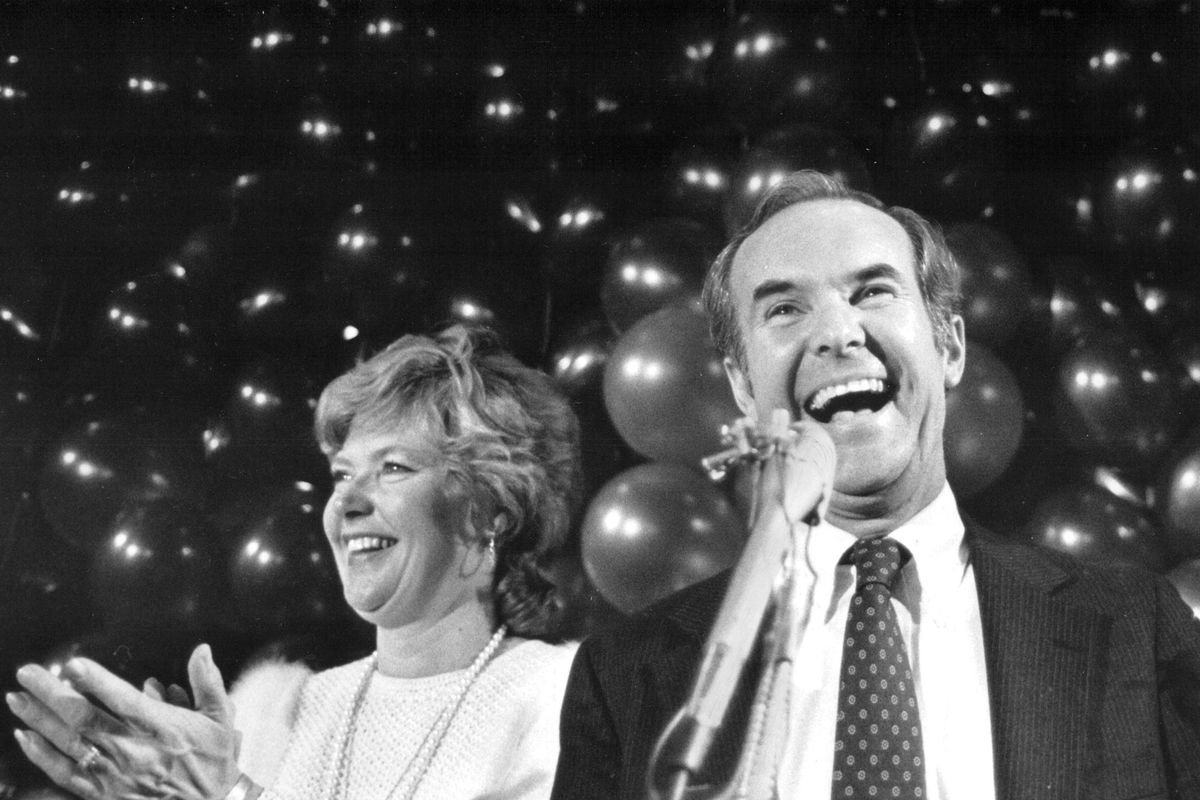

SEATTLE – When Gov. Booth Gardner first ran for the state’s highest office in 1984, many in Washington did not even know his name. That soon changed and he went on to become a two-term governor and one of the most popular politicians in state history.

From his time in Olympia to his recent campaign championing the “Death with Dignity” initiative, Gardner’s legacy is still widely felt today.

Washington’s 19th governor, he died Friday night at his Tacoma home from complications of Parkinson’s disease. He was 76.

“We’re very sad to lose my father, who had been struggling with a difficult disease for many years, but we are relieved to know that he’s at rest now and his fight is done,” Gardner’s daughter, Gail Gant, said in a news release.

“I learned so much from Booth because he was a man that led by example,” Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., said after learning of Gardner’s death. “He demonstrated that governing is about the people you serve – and serve with – by learning everyone’s name, what issues they cared deeply about, and by taking the time to work with anyone that shared his desire to make Washington state a better place to live.”

Under Gov. Gardner’s tenure from 1985 to 1993, with an economy that was largely booming, the state took notable steps on education and the environment and on expanding social and health services.

The state began to institute requirements for students to pass standardized tests before graduating from high school, raised state university faculties’ salaries, enacted the Growth Management Act, initiated the Basic Health plan and began First Steps, which helps low-income pregnant women obtain health and social services.

Gardner also had an astute eye for talent, assembling a Cabinet whose members – including former Gov. Chris Gregoire – have gone on to further prominence.

“He brought people together and he had a vision,” said John C. Hughes, author of the book “Booth Who?”, a biography of the former governor that is part of the Office of the Secretary of State’s project documenting Washington’s history makers.

Gregoire said Gardner “leaves a lasting legacy of nurturing a generation of leaders, including me.”

For Gardner, “the importance of education was paramount – investing in programs that helped young people escape poverty and drugs,” Hughes said. And he had “just his sunny optimism and idealism. He had this bully pulpit that investing in people was crucial and would pay real dividends.”

In recent years, Gardner, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1994, was perhaps best known for championing an initiative allowing physicians to prescribe lethal doses of medication for terminally ill patients seeking to hasten their own deaths. Voters passed that measure by a wide margin in 2008.

Throughout his life, Gardner had a likability that served him well, from his days as a business leader to those serving as the first Pierce County executive, from the statehouse in Olympia to the U.S. deputy trade representative in Geneva.

Born in Tacoma, William Booth Gardner was 4 when his parents divorced. Young Booth spent his childhood shuttling back and forth between his parents, Evelyn Booth Gardner Clapp, a socialite, and Bryson “Brick” Gardner, a sales manager for a car dealership whom news stories described as a free spirit with an alcohol problem.

His mother married Norton Clapp, whose family members were substantial investors in Weyerhaeuser, and who eventually became president of Weyerhaeuser.

When Gardner was 14, his mother and sister died in a plane crash in California.

After his father moved to Hawaii, Booth attended a boarding school in Vermont, then finished high school at Lakeside Academy. While attending the University of Washington, he didn’t fit in at the fraternity he joined and moved into his aunt’s house.

His aunt pushed him to find a part-time job with the city’s parks department, and it was there that Gardner had an epiphany, coaching and tutoring kids at parks and recreation centers.

“I realized I could make a difference in people’s lives,” he is quoted as saying in “Booth Who?”

At UW, he met his first wife, Jean Forstrom, who encouraged him to run for student vice president. They married four years later and had two children, Douglas and Gail.

Gardner earned an MBA from Harvard, and at 25 he inherited his mother’s fortune. Though he still penny-pinched in his day-to-day life, he contributed money to everything from establishing the Central Area Youth Association to creating Seattle Treatment Center, an alcohol-detoxification program. He became associate director of the University of Puget Sound School of Business Administration and Economics.

And he began to think about entering politics.

He did so in 1970, when he won a Pierce County seat in the state Senate against Republican incumbent Larry Faulk. He wasn’t a standout legislator, according to news accounts at the time.

When his stepfather asked him to take over running the family’s corporate empire, he agreed, managing for seven years Laird Norton Co., which included building-supply, real estate and property-management operations. He also succeeded Clapp in serving on the boards of major corporations including Weyerhaeuser.

The pull of politics drew him back in, and he won the 1981 election for Pierce County executive.

He distinguished himself as county executive, erasing a $4.7 million deficit by freezing top salaries, cutting back on contributions to nonprofit groups and eliminating jobs. He also cleaned up the reputation of the then-scandal-plagued government.

In 1984, he decided to run for governor, despite a lack of statewide name recognition that prompted his campaign staff to come up with the slogan: “Booth Who?” It wasn’t a question statewide voters asked for long, as he defeated incumbent Gov. John Spellman.

As governor, he made some notable appointments to state agencies.

Besides Gregoire, whom he appointed as head of the Department of Ecology, he named Denny Heck his chief of staff. Gardner also appointed Charles Z. Smith to the Washington State Supreme Court – the first African-American to hold such a position.

Gardner handled some political hot potatoes, including the issue of environmental protection versus property rights.

He signed the Growth Management Act (after vetoing some provisions the Legislature had passed), requiring state and local governments to concentrate growth and protect natural resources. He funded early childhood education, cut class sizes, invested in programs to help the young escape poverty, and expanded social and health services.

It helped that most of his tenure was during a time of economic prosperity.

In many ways, he was not the stereotypical politician. He hated trying to get legislators to vote a certain way – “partially because he was shy, partially because he hated to ask people for a favor,” said Wayne Ehlers, former speaker of the House, who later worked for Gov. Gardner as his director of legislative and federal relations.

Gardner preferred to govern by meeting people at schools or at the YMCA.

“I remember when I was always trying to get him to see a U.S. senator or congressman, perhaps, who was waiting to see him,” Ehlers recalled. “I’d find him sitting on the floor with a bunch of kids, visiting with them. I had to be very polite but also push him to get (to the meeting). He was like an innocent kid skipping school who got caught.”

It was that lack of willingness to dive into the rough and tumble of politics that some say led to his not being able to accomplish all he could.

He was unable to get many of the tax increases he sought, laying the groundwork for the fiscal crisis his successor inherited. While he established a high-level commission to study education reform, lawmakers rejected his proposed tax increases to finance a public school improvement plan.

In retrospect, others have given his time in office a B grade – an assessment he agreed with, according to Hughes.

“This will sound strange,” Gardner says in the biography, “but I didn’t think it was worth the price to go for an A.”

After Gardner ruled out a run for a third term, President Bill Clinton appointed him a deputy U.S. trade representative. He served as the U.S. ambassador to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade – the precursor to the World Trade Organization – in Geneva.

In 2001, Gardner and his wife, Jean, divorced. He then married Cynthia Perkins, a Texas resident Gardner had met in Geneva. The two later divorced.

Aside from applying for superintendent of the Eatonville School District (a move that perplexed many and a position for which he was not ultimately chosen), Gardner kept a relatively low profile after leaving state office. That is, until he announced in 2006 that he would head up an “assisted death” initiative in Washington state.

Washington voters in 1991 had rejected a measure that would have allowed doctors to write prescriptions to hasten death and administer lethal injections to terminally ill patients who weren’t able to take the medications on their own.

The initiative that Gardner eventually championed was modeled after an Oregon law that, while allowing doctors to write the prescriptions to hasten death, said the patients must administer the medication themselves.

Gardner was candid about how his own 1994 diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease affected the decision to get back into the political fray.

“Since I’ve had Parkinson’s, obviously I’ve thought about the end,” he said in a 2006 Seattle Times story. “When the day comes when I can no longer keep busy and I’m a burden to my wife and kids, I want to be able to control my exit.”

Ironically, the “Death with Dignity” initiative, which voters approved with nearly 58 percent of the vote, did not apply to the former governor because his disease is not considered terminal.

Besides his daughter Gail and her husband, Stephen Gant, of Tacoma, Gardner is survived by son Douglas Gardner and his wife, Jill, of University Place, and eight grandchildren.