fear of being hawking

Actor Redmayne strives to truthfully convey physicist’s condition

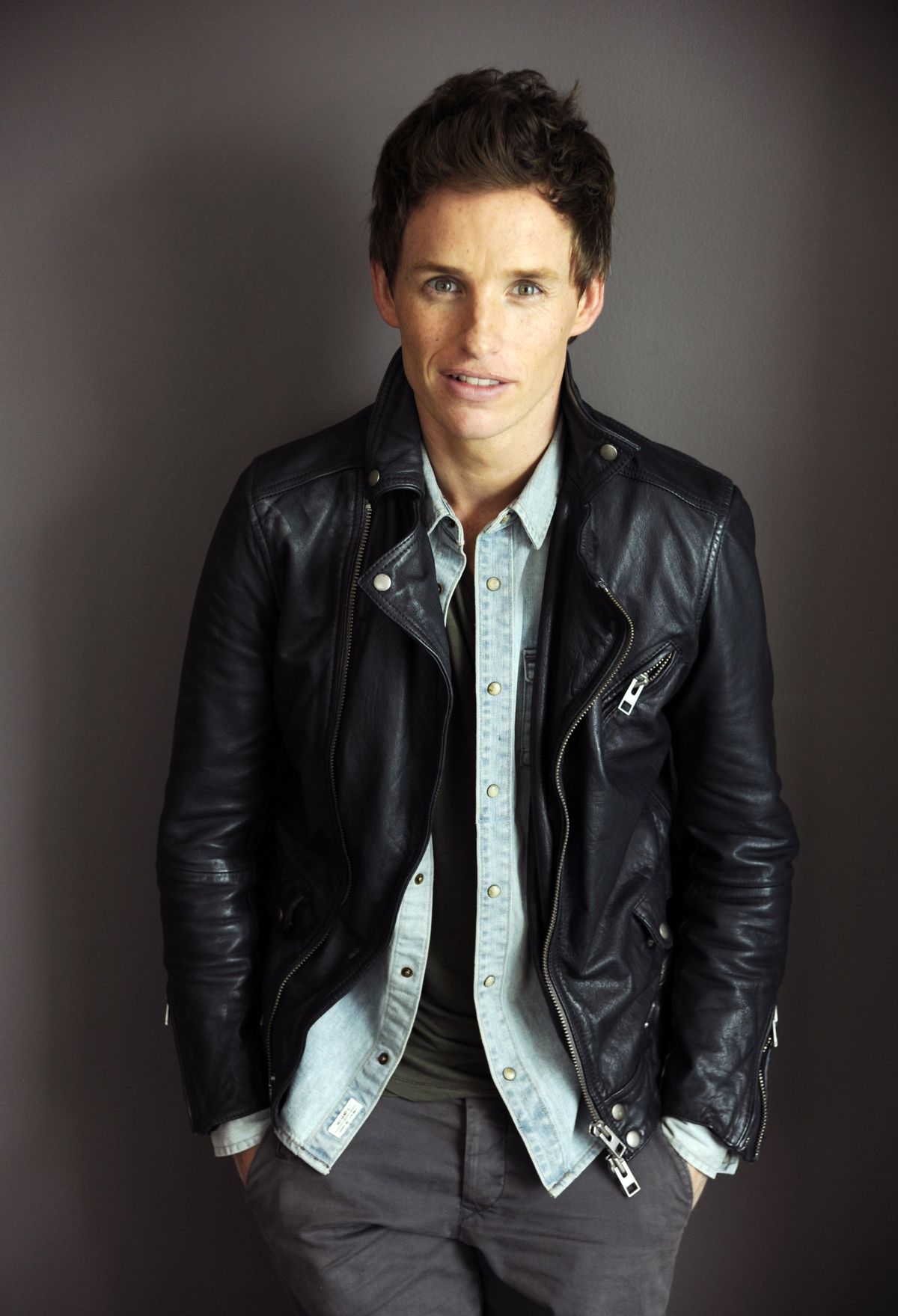

TORONTO – At age 32, Eddie Redmayne is still boyish, with freckles not always visible on screen, a generous head of hair, a wardrobe that includes both a black leather jacket and Converse sneakers, and a humility about the praise that welcomes him as he walks into a hotel room one Sunday morning.

In “The Theory of Everything,” he plays Stephen Hawking, who was 21 years old in 1963 when he was diagnosed with motor neuron disease (an umbrella term that includes Lou Gehrig’s disease, or ALS) and given two years to live. The brilliant astrophysicist defied all odds and today, reliant on wheelchairs, speech synthesizers, nurses and aides, is 72.

“As an actor you dream of being able to tell extraordinary stories about extraordinary people, but the stakes felt so high,” Redmayne told a handful of journalists during September’s Toronto International Film Festival where the movie had its world premiere.

Hawking’s family, especially his first wife, Jane, had allowed the filmmakers to tell their story, and Redmayne spent four or five months meeting with other patients and doctors. “People invited me into their homes, people who subsequently died from the disease,” he said, and he wanted to represent their experience truthfully.

“It was one of those jobs I went bullheaded into trying to get, and then once I got it, I had this moment of euphoria, followed by this sledgehammer of fear. When you’re that intimately involved in something, when it begins to creep out into the world, it’s quite scary.”

It was greeted with immediate Oscar buzz for him and co-star Felicity Jones as Jane Hawking, whose memoir “Travelling to Infinity: My Life With Stephen” is the basis of the movie. The couple split up after more than 25 years of marriage and three children; both married again, although Hawking eventually divorced his second wife, a nurse.

But that’s getting way ahead of the story and movie, which started on a note of insomnia. Redmayne had been so nervous before being picked up at 5 a.m. the first day of filming that he couldn’t sleep.

“The first scene was that scene where we spin around; Felicity and I are totally healthy, young. You see the foot beginning to drop. Then, at lunchtime, it was on two sticks (canes), and in the afternoon, it was in the third wheelchair.”

In one exhausting day, he had to lay down three markers for what was to come. It was financially prohibitive to shoot the movie in chronological order, so the actor had to be rigorous in charting where Hawking was in the process. For instance, once a finger stopped moving, it couldn’t move again: In MND, nerve cells that control muscles degenerate and die.

The first call about the role from director James Marsh came when Redmayne was working on the sci-fi adventure “Jupiter Ascending” for the Wachowski siblings.

“I had to do, like, 8 zillion sit-ups for a month to try and get ripped, and the guy in charge of making me get ripped works with motor neuron patients. He was telling me it’s the foot that goes first, the foot drop. That was my first knowledge of it.”

Redmayne supplemented his study with medical experts and clinic visits with collaborations with a makeup artist, costume designer, vocal coach and choreographer or movement director. He also read books by and about the Hawkings and watched footage and documentaries about the scientist.

Through the movie, Hawking’s neck begins to permanently tilt to one side, one shoulder moves up like a frozen see-saw, his hips shift, fingers curl or wilt, and he eventually communicates partly by raised eyebrows.

“It was a lot of time spent in front of the mirror learning to use muscles that I had never used before,” he said. One side of Redmayne’s face actually became more lined and muscular because of the way he held his mouth and manipulated the muscles.

“It’s about being real, about the brutality of the illness, not sugarcoating that, while still making people understand this disease is like being in a prison with the walls getting smaller every day.”

But the project also was about capturing Hawking’s intelligence and sense of humor, and that was underscored when the actor met the rock star of physics five days before filming started.

“When you’re in a room with him, he’s just genuinely funny, flirtatious. He emanates this kind of wit and humor – that was the thing I took away. Every single scene of this has to be, whatever obstacles are thrown at him, he is a fighter and he finds hope in the darkest of places, with Jane as his catalyst or backbone.”

Hawking visited the set during shooting of the May Ball, a grand white-tie dance made even more spectacular on screen with fireworks. As if on cue, Hawking arrived with a nurse, and he was silhouetted against the night sky, with his computer screen illuminating his face.

The London-born Redmayne, who played the adult son of Angelina Jolie and Matt Damon in 2006’s “The Good Shepherd,” is a Tony and Olivier winner for the play “Red” and sang “Empty Chairs at Empty Tables” as student rebel Marius in the movie “Les Miserables.”

It had been his work in the little-seen “The Yellow Handkerchief,” alongside Kristen Stewart and William Hurt, that helped to convince the director he could “jump off a cliff” for this role and be brave enough to make mistakes. “That’s the thing James Marsh is a genius at,” and Redmayne said he works best with directors who are willing to indulge actors who start sentences with, “I’ve got an idea and it’s probably rubbish …”

“For me, the most interesting work happens when people make mistakes,” or go off page slightly as Jones did in a scene set in the couple’s kitchen where a bed has been moved to spare Hawking the stairs. Stephen says “Thank you” to Jane, and she asks, “What did you say?”

And he has to repeat his expression of gratitude in what proves a salient, brilliant bit of improvisation.