A new dawn: Restoring the Clark Fork Delta

Restoration effort aims to control erosion, protect ecosystem of 5,600-acre wetlands

On a fall afternoon, the Clark Fork Delta is a place of astonishing beauty.

Yellow-green grasses glow against the denim-blue of the Clark Fork River as it empties into Lake Pend Oreille. Each detour down the braided river channels reveals a surprise: an eagle’s nest, a pair of redheaded ducks, a golden stand of cottonwoods.

In a kayak and in hip waders, Katherine Cousins has explored this fertile meeting place of land and water. Amid the striking scenery, she sees an ecosystem in peril.

“The delta is melting away,” said Cousins, an Idaho Department of Fish and Game mitigation biologist.

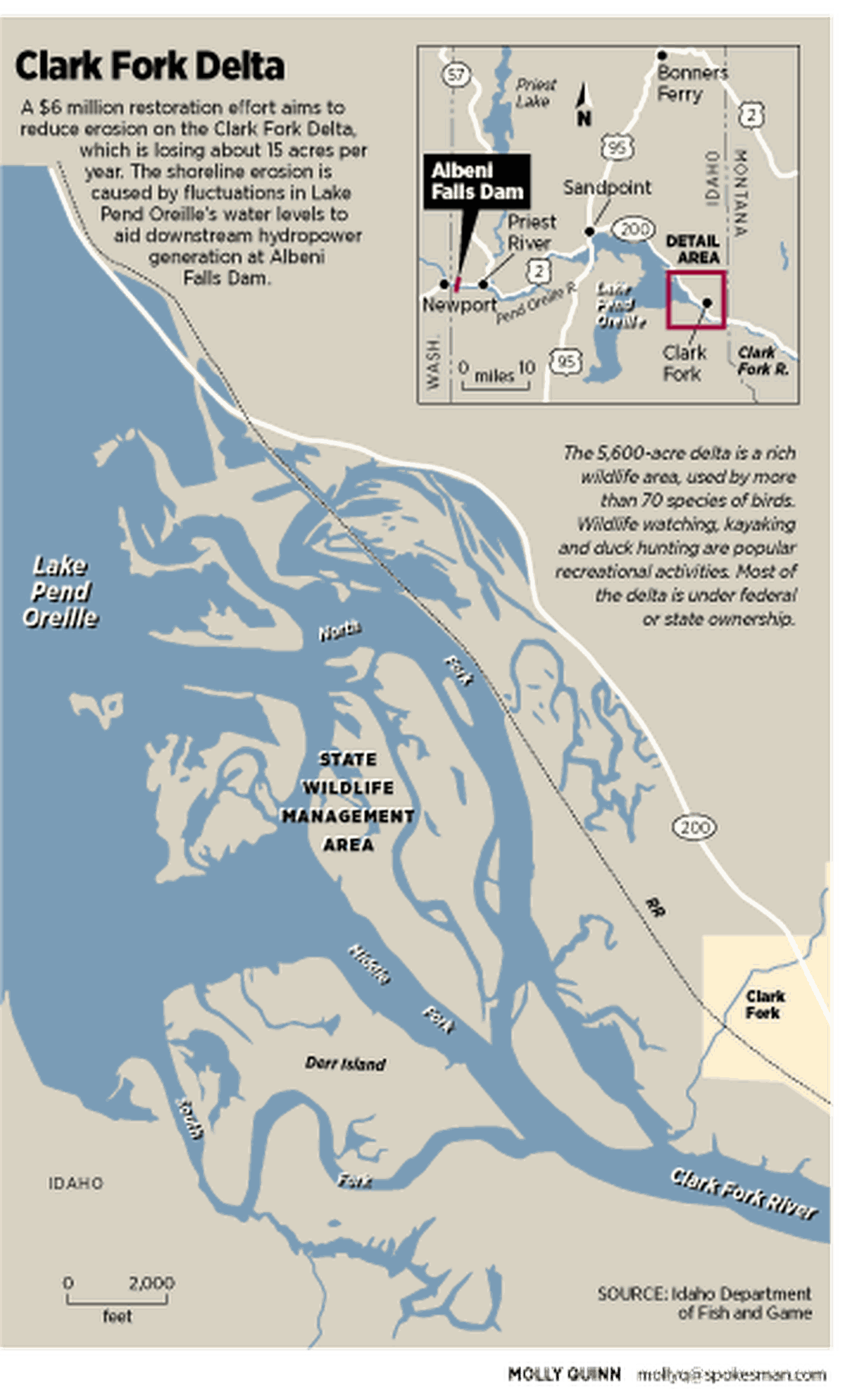

Each year, the 5,600-acre delta loses about 15 acres to erosion. The culprit is fluctuating lake levels that benefit hydropower production but corrode the delta’s shoreline.

To Cousins, who started doing wildlife surveys on the delta a decade ago, the rapid loss of land is alarming.

“You can see the urgency of the situation,” she said, pointing out an isolated gravel bar that was once part of a delta island.

Waves have now breached part of the gravel bar. When it disappears, the waves will start battering the shoreline, undermining a grove of cottonwoods.

But the Clark Fork Delta – which ranks among Idaho’s 10 most important wetlands – has a committed group of advocates.

Cousins is leading a $6 million effort to preserve the delta. The work involves federal and state agencies, consultants, conservation groups and the Kalispel Tribe, whose ancestors camped, hunted and gathered roots on the delta.

Money for the restoration work is coming from the Bonneville Power Administration and Avista Corp. as mitigation for the three dams causing the delta erosion.

BPA sells the electricity from Albeni Falls Dam, which drowned 15,000 acres of wetlands and deep-water marshes around Lake Pend Oreille when it was built in the 1950s. The dam also controls lake levels, which rise and fall about 11 feet each year.

The fluctuations benefit flood control, power production and recreation, but speed the erosion. When the lake is drawn down, the delta’s waterlogged shorelines collapse and slough off.

Avista’s two dams on the Clark Fork River also affect the delta by trapping sediment and some of the logs that would have flowed downstream, rebuilding the delta’s shoreline.

“The delta is not getting wood, it’s not getting dirt. It’s getting hammered by wind and erosion from the lake,” Cousins said.

“We’re fighting the effects of 60 years of dams, which have changed the hydrology of the area,” said Brian Heck, an engineer for Ducks Unlimited, a contractor for the project.

Restoration work starting this fall targets 680 threatened acres of the Clark Fork Delta. Heavy equipment will be used to rebuild shorelines and raise the height of partially submerged areas. The intent is to preserve what remains of the delta and – if all goes as planned – start to recover some ground.

Most of the delta is in state and federal ownership. “It’s a special place that’s been disappearing because of changes we’ve made as a society,” said Chip Corsi, Idaho Fish and Game’s regional supervisor in Coeur d’Alene.

But, “there’s still a lot of remaining delta to protect,” he said. “And if we can build some back, we’ll start reversing the loss.”

Thriving wildlife zone

As Cousins navigated a motorboat through the delta’s channels on a recent afternoon, she pointed out the fronds of underwater plants. The delta’s biological importance to the region starts here, with dying vegetation that forms the basis of a rich food web.

Detritus – particles from the breakdown of decomposing plants – feeds protozoa, bacteria, fungi and larvae, which become food for foraging fish, frogs, worms, insects and birds.

More than 70 bird species are found on the Clark Fork Delta, including flycatchers, kingfishers, cat birds, herons, loons and dozens of other waterfowl.

During a recent bat study, where Cousins documented six species of bats on the delta, she heard so many owls hooting that she’s now planning an owl survey.

Deltas are fairly rare on the landscape, but they’re intensely productive zones for wildlife, said Deane Osterman, the Kalispel Tribe’s natural resource director.

The Clark Fork Delta is both a mixing zone for the lake and the river, and a corridor linking the Bitterroot and Cabinet ranges.

“If you poke around in the delta, you’ll encounter a whole bunch of different habitats, and a whole bunch of different critters,” Corsi said. “You can find tracks from frogs, from raccoons, beaver, mink, elk, bear and moose.”

Wildlife watching is one of the delta’s top recreational activities, along with duck hunting, kayaking and fishing.

But as productive as the delta is for wildlife, there’s room for improvement. Part of the restoration plan calls for eradicating reed canary grass, an invasive monoculture that’s taken over parts of the delta, choking out native plants.

“It’s too tall for nesting waterfowl, and nothing really eats it,” Cousins said. “We’re going to mow it, spray it and bury some of it.”

In its place, she’ll cultivate reeds, cattails and other native wetland plants.

Re-establishing native plants on the Pack River Delta, which is farther to the west on Lake Pend Oreille, led to exponential growth in waterfowl use.

Five years ago, Cousins managed a restoration of the 640-acre Pack River Delta. It was a demonstration project leading to the larger, more challenging Clark Fork Delta work, she said.

The Pack River, which is undammed, deposits more than 200,000 tons of sediment into the lake annually. Once the erosion was reduced, the delta began rebuilding itself.

The Clark Fork River doesn’t have a large sediment load to aid the restoration work. But much of the construction and engineering work is similar.

To protect the Clark Fork Delta’s sloughing shoreline, contractors will build rock walls and weirs that redirect the water’s current. To mimic a natural shoreline, willow shoots will be planted among the rocks.

A new channel will be dug to improve fish habitat. Material from the excavation will raise the height of partially submerged islands.

The delta construction will wrap up next year, followed by an extensive replanting effort.

Nature will take care of some of the revegetation. From the Pack River Delta project, Cousins learned that black cottonwoods will come back without human help. And, when submerged soil was moved around, long-dormant seeds of other plants sprouted. Evening primrose was one of the surprises.

“It’s a rare plant and it’s all over the Pack River Delta now,” Cousins said. “Our botanists get really excited seeing it.”

Idaho Fish and Game officials anticipate that the current work on the Clark Fork Delta will be the first of several projects. In total, about $12 million of delta restoration work has been identified, said Corsi, the Fish and Game supervisor.

Avista contributed $3 million to the current delta work, which satisfies the financial commitment the utility made when its Clark Fork dams were relicensed. But BPA remains a candidate for future funding.

Last year, the Idaho Conservation League sued BPA over the operation of Albeni Falls Dam, saying more needs to be done to address Lake Pend Oreille’s eroding shoreline. The state of Idaho, however, agreed not to sue BPA in return for the $3 million it contributed for delta restoration money.

Corsi said he expects additional talks with BPA about future contributions for wildlife mitigation.

Among wetlands to preserve, the Clark Fork Delta gets a high ranking.

“It’s a pretty incredible place,” Corsi said. “When I go there in a canoe, I feel like I’m going back in time.”