Former Cougars men’s basketball coach George Raveling in Hall of Fame as a contributor

It was a frigid, foggy December Monday, and inside the lifeless Spokane Coliseum the Washington State Cougars were trying – and mostly failing – to commit actual basketball.

The old barn was a sad enough place – famed columnist Jim Murray once asked where they stored the dirigible on game nights. But on this evening it was especially grim, as maybe 450 people had sought shelter to watch the Cougs against what was supposed to be a Division II pastry, Eastern Montana College. In the middle of a scoreless first overtime – the Cougs would lose in three – WSU coach George Raveling left his bench and took a knee in front of the press table, presumably for a better view of the inaction at the far end of the floor. Instead, he looked over at two reporters and sighed.

“You guys got any openings down at the paper?” he wondered.

The guess here is, when Raveling returned his gaze to the court that night, he didn’t see the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame holding the door open for him.

And yet here he is.

When the Hall revealed its 12 finalists for 2015 induction Saturday, it also announced a group of five “direct elects” that will be enshrined in September – Raveling going in as a “contributor.”

Those contributions weren’t broken down, but possibly include everything from bridging a broad, if unremarked upon, racial/cultural gulf as an African-American coach in a rural outpost “where there were maybe 10 black people” to his work for Nike in international basketball circles to finding the humor in a bad loss in an empty building.

“I guess I have a broad resume,” he cracked in a telephone conversation Saturday.

He also has a great capacity for gratitude.

“Honestly, I’ve had a minimum of disappointment or regret,” he said. “I’ve lived a rich life and I’m really blessed. This wasn’t anything I ever envisioned, but it’s something that reflects significant purpose. And if you accept something like this, you also have to live up to the standards of that award.”

Being a contributor suggests a lifetime spent growing the game. As he’s now 20 years removed from his last coaching gig, Raveling has been working the soil behind the scenes in ways difficult to quantify – and even he admitted that “committee work isn’t very sexy.”

So let’s cite a more obvious contribution. He put people in the seats at Beasley Coliseum, and then made them get up off their fannies.

Click over to a Wazzu game on Pac-12 Networks these days for a demonstration of just how difficult that is.

“That’s what made the job so special to me in so many ways – the emotional engagement, especially with the students,” said Raveling, whose nine-year run at Wazzu included the opening of Beasley in 1972. “People come up all the time and tell me, ‘I was at Washington State when you coached and those were such fun days.’ I mean, students would camp out to get the best seats.”

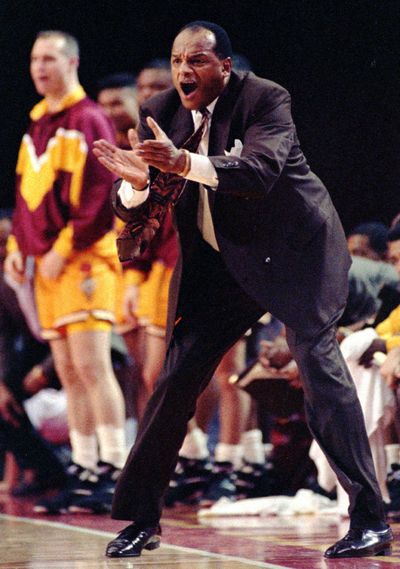

And not just to watch the Cougs, but to watch Raveling show off a 30-inch vertical leaping off the bench to protest a call or set a defense.

Even when he came back to town as the coach of USC, he had the touch. As he worked a ref, the student section chanted, “Sit down, George!” – and Raveling started clapping along in rhythm.

The chant turned into a cheer.

“My third year (at WSU), we might have won eight games (it was 10), and at the end of the season (athletic director) Ray Nagel called me in,” Raveling said. “I thought he’s going to fire me – or tell me he will if I don’t win next year. Instead, he said, ‘I’m going to give you a raise – and just think what will happen when you start winning.’

“No way in hell that happens today.”

Follow George Raveling on Twitter these days or click on his website, and you’ll get more philosophic nuggets and perspective than Wazzu war stories.

“It’s an ethnically, racially, socially blind game,” he said. “It might be the one place in our society where race and religion and politics have no relevance – for 40 minutes we can put those things aside that challenge us in everyday life, and learn to make sacrifices for the greater good.

“When you stop and think about it, it’s one of the great teaching venues we have. We just don’t stress enough to young kids about the opportunity. But when you get to my age and look back, you think, wow, I had no idea these things were going to impact my life and value system.”

George Raveling’s contribution? He’s still trying to get people on their feet for basketball.