Spokane County records missing a piece of history

No clues for the planning gap were left on a single blank page between documents in the county’s old plat books, the corners of its pages smudged from years of heavy thumbing by county planners and engineers.

“We have not been able to get an adequate answer,” Dalton said. “The only thing that we can come up with is, ‘It was World War I, folks.’ ”

A definitive answer for the inconsistency of the documents – County Planning Director John Pederson calls them the legal proof of planning during the World War I era – is a task suited to historians and archivists. Dalton would prefer hiring a graduate student to research the question, but the auditor’s office coffers simply couldn’t support it with the housing market still struggling through recovery, she said.

But clues about the missing documents can be found in the historical record, and point to a political reality that is much more familiar to today’s climate of partisan politics than a nation and region at the threshold of global war.

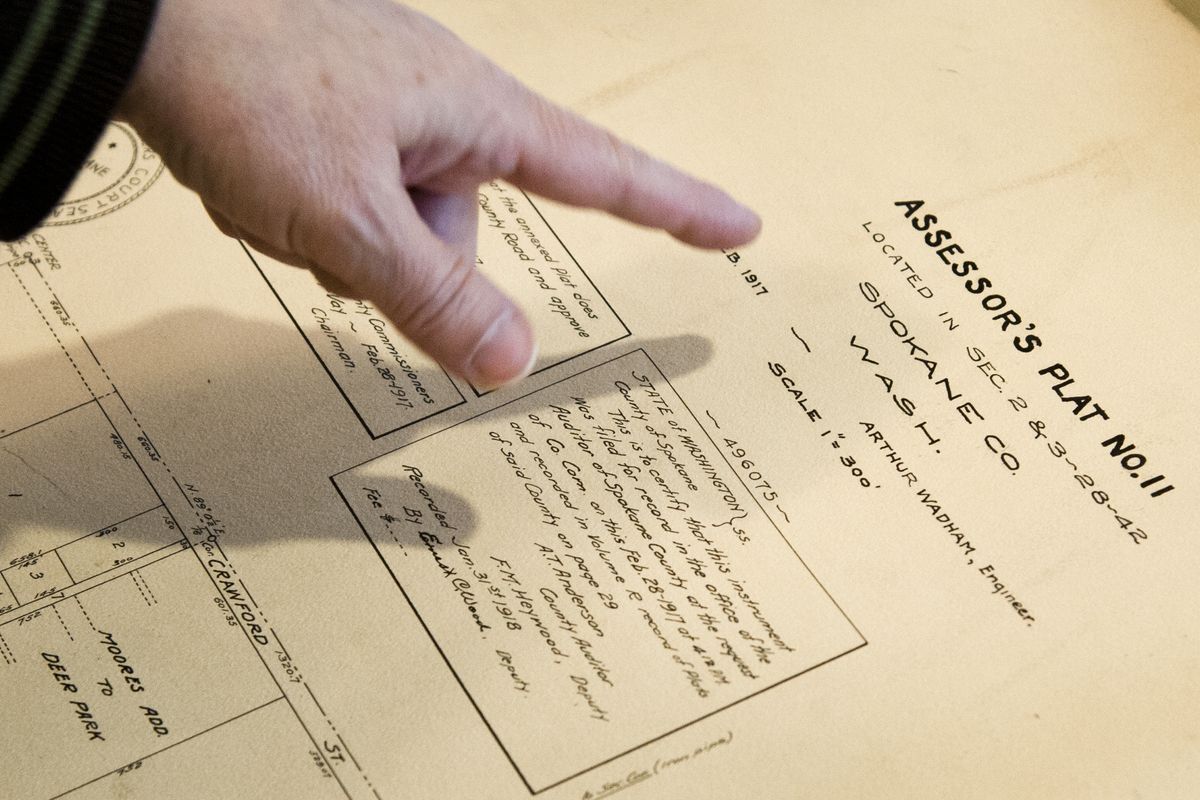

Last month, Lee Pierce turned with cloth-gloved hands the yellowed pages of County Plat Book R, containing the original records of how county engineers laid out housing developments, commercial buildings and even cemeteries during the early days of the 20th century.

“Saltese Cemetery – that was January 1917,” said Pierce, an archivist at the Cheney branch, pointing at one of the plats recorded during a period of apparent upheaval in county recording. A grid of graves is laid out on the page, a network of roads showing where mourners could enter and exit the property. The cemetery was dedicated that month and remains on East 32nd Avenue, west of Liberty Lake. About 470 people are buried there, according to records from the Washington State Digital Archives.

Maintaining a complete record of county platting documents is essential to planning future growth, Dalton said, which is what makes the initial appearance of missing documents so alarming.

“You can’t make changes without going back to the original,” she said. “Everything that happened in Spokane and Spokane County couldn’t happen without this.”

Upon closer inspection, archivists found planners simply skipped what appears to be an arbitrary amount in their numbering scheme, leaving Dalton and others stumped.

Dalton also looked at marriage licenses and other official documents at the time, finding no similar discrepancies. Although World War I was raging in Europe during the period, the United States didn’t join in the fighting until 1917. Plat recording also continued unabated through World War II and other conflicts throughout the 20th century, she said.

It’s possible county staff at the time realized there had been a gap in recording and just jumped to an arbitrary number when new leadership took over. The mystery is based on the fact that one plat is numbered 762, then the next one that appears is numbered 900. No explanatory note exists in the record, an absence current recorders try to avoid.

“You don’t want gaps in history, if you can help it,” Dalton said. When a software programmer caused a hiccup in recording several years ago and erased 1,000 documents, Dalton said, she made a point to include a notification the error had occurred.

Without that information, explaining gaps in history falls to archivists like Pierce and Debbie Bahn, who have worked with Dalton to put thousands of county records online. Bahn said reconstructing history without a primary explanation is a painstaking task for archivists, using records from other counties and other primary documents, such as letters, diaries and even newspapers, to get a sense of the times and a clue about what isn’t in the record.

“We describe not only what the records contain, but what gaps of information exist,” Bahn said.

A plateau in growth

Several records exist that could explain the upheaval in recording around 1915. Property tax levies, population totals and economic indicators all show stagnation in the county around that time.

Charles Mutschler, archivist for Eastern Washington University and an adjunct professor of history at the school, said the strain on public services, such as property recording, during the pre-World War I years could be attributed to many different things, based on records that survive.

“The pressure of the war created economic opportunities, which created pressures in other parts of the economy,” Mutschler said. The demand for grain by armies fighting in Europe probably sent many able-bodied men to the fields of the Palouse to work in agriculture, he said. That could have, in turn, led to a shortage in civic employees.

A lack of growth could also explain the recording oddity.

The county’s population more than doubled between 1900 and 1910, from 57,000 people to 139,000 people, but only grew by 2,000 people during the 1910s. The automobile had not yet taken hold, but streetcars made living in areas outside the main drag viable, Mutschler said, which would have created the need for planning in outlying residential areas in the early 1910s.

But that need may have tapered in the run-up to the war, and as Spokane’s population explosion eased.

“By 1910, it’s pretty much plateaued,” Mutschler said. “Spokane has filled up. The Milwaukee (transcontinental railroad) is completed just as the Panama Canal opens in 1914, and freight starts moving by ship to the south.”

Assessed property values hit a seven-year low in 1916, according to records published in the Spokane Chronicle at the time. It would take until 1924 before home values in the county reached 1915 levels again, indicating a lack of construction and renovation.

But Dalton said other record-keeping did not show any signs of waning. And the Chronicle reported in 1917 total county tax receipts were up, and building in the county that year was the highest among similar-sized counties in the Pacific Northwest.

The newspaper also reports that the gap in platting could be attributed to one man’s leadership, and the political defections that occurred in the run-up to the 1916 elections.

‘Playing petty politics’

John Strack felt slighted.

The man credited with laying out plans for half the city of Spokane was being called out in the pages of The Spokesman-Review and Chronicle for his work as county engineer overseeing highway construction to outlying areas. First there were accusations the roads were not being built to safety specifications, then came the assertion that Strack had approved use of subpar sheet metal. In April 1915, he could stand the criticism no longer.

“Why is nothing said of the good roads this department is building?” Strack declared in a column he penned for the April 11 issue, later blaming county commissioners and others for what he called “playing petty politics” in the media.

Strack had spent two terms as engineer for the city of Spokane before being elected to serve as county engineer just before the start of World War I. The engineer’s office, including deputies, signed off on all plats filed with the county. But the relationship between Strack and his office grew strained toward the end of his final term in 1916.

Under Strack’s watch, about 100 miles of highway connecting Spokane to Deer Park and the Palouse were built, but not without controversy. In addition to his 1915 letter to the Spokesman-Review, which at great length defended his road work and thrift with taxpayer dollars, Strack found himself denying a mutiny within his ranks in the summer before the 1916 election.

In June, one of Strack’s deputies, Charles McClung, was involved in a public spat with a colleague, Ernest C. Wood. The argument led to Wood’s resignation, leading the Chronicle to declare, “The county engineer’s office will become the center of the bitterest county fight before the republican primaries.”

Strack, who backed McClung in the election and left office at the end of the year, once again bristled at the newspaper’s notion of discord in the ranks, calling it “political bunk.”

Allen R. Scott, not McClung, took over the county engineer’s office in 1917. That’s about the time the jump in platting that puzzles Dalton occurred, though the dates don’t match perfectly.

Strack would enter private practice and work until just a few weeks before his death in 1931. His house, heralded in 1907 for its modern construction and amenities, still stands at 1206 E. Fifth Ave. and is listed as a historic property.

The discord in the partisan county engineer’s office is not linked to any official record in the newspapers of a hiccup in platting new real estate. But it is a major clue in piecing together what appears to be an arbitrary gap in history for Dalton and others, and a more specific answer than the interruption of war.

Uncertain memories

The definitive answer for the head-scratcher in old county plat books may be found in records that are destroyed or decaying in someone’s attic or garage. But the theory that the discord in the county engineer’s office may have caused the problem now faced by archivists disappoints Dalton.

“If there was some kind of strife in the office that kept those official duties from being performed, then that’s really unacceptable, in my opinion,” she said.

Not only is it discouraging from a political standpoint, but also for those trying to piece together the history of the county, Dalton added. The mystery underscores the need to provide accurate record-keeping and note all outside circumstances that get in the way of government functions. Without that, Spokane’s future residents will be forced to conduct the same search for potentially nonexistent evidence to plug gaps in the story we leave behind, Dalton said.

“It only takes a few years for a memory to fade, or be gone,” she said.