This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: Behind the dramatics, a real issue with university student-conduct boards

You may not have heard much about this – since it didn’t involve a football player and a state senator braying at the regents – but there was an appeals court ruling this month that ordered colleges and universities in Washington to do a better job allowing students to defend themselves in expulsion cases.

Like many of those cases, the one the state Court of Appeals justices considered is foggy and troubling. It makes you question whether universities should be operating as quasi-judicial triers of fact, but it also makes you understand why sometimes they might need to – why a college, responsible for the safety of the campus environment and for enforcing federal laws prohibiting discrimination, might want to set a higher bar than merely “not guilty.”

The state Court of Appeals ruled on the case Dec. 1. It involved a 40-year-old doctoral student from Saudi Arabia, enrolled at Washington State University. He was arrested in 2014 and accused of raping and molesting a 15-year-old girl – accusations that would be Class C felonies if he were found guilty, the court said.

The man, Abdullatif Arishi, was charged under the student conduct process with violating standards of student conduct and policies prohibiting discrimination, sexual harassment and sexual misconduct. He said he believed the girl was 19, and she had represented herself as such online. The conduct board, relying on the testimony of police officers, concluded that “once (Arishi) met her face to face (he) knew she was too young.”

The university expelled him after a one-hour hearing – its usual procedure. He was a semester away from concluding his Ph.D, and the ruling effectively ended his pursuit of an education in America, he said.

“Under the university’s student conduct procedure, the rules of evidence were not applied, only board members could question witnesses, proposed student questions had to be submitted in writing to a board member who would decide whether or not to ask them, and Mr. Arishi had no opportunity to subpoena witnesses or documents,” the Appeals Court ruled. “Mr. Arishi attended the hearing with the lawyer representing him in his pending criminal case, but pursuant to student conduct rules, the lawyer could only act as a private advisor and could not address witnesses or the conduct board.”

These rules, the court found, were insufficient. State law covering adjudications by state agencies provide for two kinds of hearings – brief and full. In cases of expulsions or allegations of actions that would be considered criminal, the court found, a full hearing is required, allowing full representation by an attorney, reasonable advance notice, a presiding officer who can issue subpoenas and orders, and the right of the accused to object, call and cross-examine witnesses, and present evidence.

If any of this sounds familiar to you, I’m guessing it’s not because you followed the Arishi case. No, these complaints are many of the same ones that have been raised this football season by the bellicose defenders of WSU football players who have been disciplined for fighting and other boorish behavior. That outpouring has been a reminder that if you want to get attention and wield influence and rally crowds for “justice” – if you want to get state Sen. Michael Baumgartner to offer you a job or shout at regents or call people bigots for you – it’s very important that you be a football player.

Be that as it may, the “Justice for Nose Tackles” crowd made the same arguments as the appeals court.

Baumgartner did not want to comment for this column. But he’s made clear on Twitter and in other public remarks that he intends to bring legislative action aimed at the rights of the accused in student conduct cases.

The university, meanwhile, has quickly complied with the court ruling by moving to full hearings on matters of expulsion, while bringing in a consultant and creating a task force – a higher-ed two-fer! – to consider further changes.

Colleges and universities around the state have adopted different rules for student conduct hearings. At the University of Washington and 11 other schools, a case like Arishi’s would have resulted in a full hearing. Twenty-seven schools apply some form of brief adjudication hearings such as those at WSU; the university’s attorney told the court that the school had never, to her knowledge, offered a full adjudication to any student.

The Arishi case is a reminder of one of the key realities of the fact-finding pursuit of justice: that the strict boundaries of evidence often do not align with incomplete, vague or contradictory facts. It’s also clear that the university might well have determined that there was sexual misconduct under school rules – a broader standard than criminal law. In their ruling, the appeals court justices acknowledged that they were asking colleges to take on a difficult and burdensome task in developing “the capacity to conduct timely full adjudication.”

But the justices offered a suggestion: Colleges could outsource the job to the state office of administrative hearings, which could assign an administrative law judge to handle the proceedings with a little legislative tweaking. If that were possible, “it will relieve educational institutions of that burden and provide independence that could be valuable in these difficult cases.”

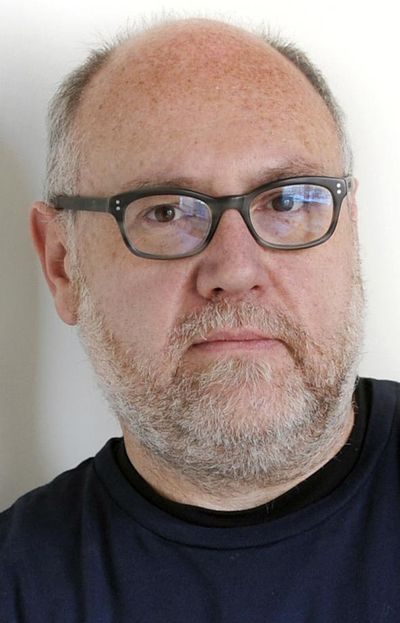

Shawn Vestal can be reached at (509) 459-5431 or shawnv@spokesman.com. Follow him on Twitter at @vestal13.