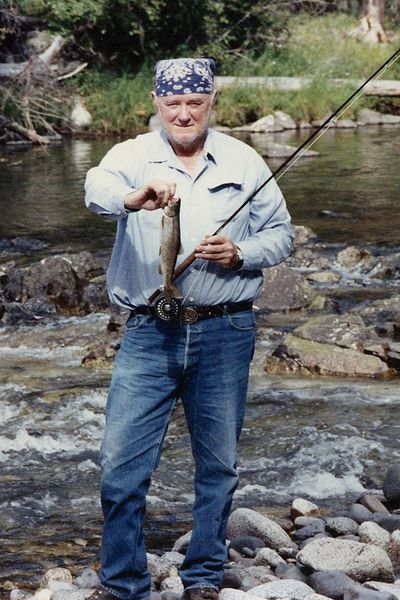

Outpeople: Thomas thought ahead for wildlife, public lands as Forest Service chief

Jack Ward Thomas helped the U.S. Forest Service see beyond the trees.

A wildlife biologist who rose to the top of the agency during some of its most turbulent years, Thomas was remembered in Missoula as both a conservationist and friend.

“His death is a great loss,” said Chris Servheen, recently retired grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “His appointment to be chief was really the turning point in the Forest Service becoming more a multiple-use agency, transitioning out of that stereotype of ‘all we do is cut trees.’

“That’s what made him really unique – he wasn’t a timber guy. He was instrumental in leading the Forest Service into that bigger view of things.”

Thomas died of cancer on May 26 at his home in Florence, Montana. Current Forest Service Chief Tom Tidwell said Thomas faced several years of declining health the same way he did everything – scientifically, optimistically and straightforwardly.

“I will miss Jack, not only for his dedication to science and his conservation leadership, but also for his stories,” Tidwell said in an email. “Even when he and I were in a lively debate, Jack would have me laughing before we were done.”

Thomas joined the agency in 1966, and was Forest Service Chief from 1993 to 1996. In 1992, he led a non-laughing conference on how the agency should balance logging goals against the possible extinction of spotted owls in Pacific Coast forests.

“That was where Jack hit the larger stage,” said Jim Lyons, deputy assistant secretary for land and mineral management at the Department of Interior.

Lyons had asked Thomas to put together the science panel exploring how cutting old growth forests affected watersheds and wildlife habitat – a concept that became known as ecosystem management.

“Under the Reagan administration, there was a huge push to get the timber cut out, and that’s what got us into the mess with spotted owls,” Lyons said. “We were making political decisions to keep cutting, cutting, cutting – regardless of the biological consequences, and that led to court decisions enjoining timber sales.

“Instead of this one-dimensional view of success in timber harvest, Jack saw the forest in the context of multiple use.”

The perspective impressed President Bill Clinton, and Lyons recommended Thomas to become chief of the Forest Service. It was a controversial move.

“The rank and file did not want Jack to be chief,” Lyons said. “He was a wildlife biologist, and every chief before him was forester or an engineer. They fought his appointment, and in the end they tried to block his normal appointment as a senior executive, even though he was a senior scientist.

“We had to get the White House to appoint Jack as chief – the first and only time that’s been done.”

Thomas started with the Forest Service in 1966, working as a research wildlife biologist in Morgantown, West Virginia. He published more than 600 articles and books, including the frequently reprinted “Invite Wildlife to Your Backyard” in 1973 and “Elk of North America” in 1982.

“We knew that as the Elk Bible,” said Bob Munson, one of the founding members of the Missoula-based Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation. “Jack was one of the biggest sparks to light the RMEF back when we got started in 1984. We’ve now got more than 500 chapters and 220,000 members, and I attribute a lot of that to guidance right from the mouth of Jack Thomas.”

After retiring from the Forest Service in 1996, he became the Boone and Crockett Club professor of wildlife conservation at the University of Montana. There he continued expanding his concept of melding strong research with landscape management – something he called “bio-politics” rather than political science.

“Jack was somebody who was so good listening to all sides, and coming up with solutions that bridged what often was a wide divide between the science of conservation and public policy,” said Dan Pletcher, retired director of UM’s wildlife biology program and colleague of Thomas’ for a decade. UM awarded Thomas with an honorary doctorate this spring, but he was too ill to attend the ceremony.

Other awards and honors he received over his career included the USDA Distinguished Service and Superior Service Awards; Elected Fellow, Society of American Foresters; National Wildlife Federation, Conservation Achievement Award for Science; The Aldo Leopold Medal, The Wildlife Society; General Chuck Yeager Award, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation; and USDA FS Chief’s Award for Excellence in Technology Transfer.

He served as president of The Wildlife Society from 1976 to 1977.

Retired Lolo National Forest Supervisor Orville Daniels said Thomas tempered his approach by warning against “the arrogance of science.”

“One thing he said to President Clinton was that the ecosystem is not only more complex than we think it is, but it may be more complex than we can think,” Daniels recalled.

“We have to do the best we can because we probably will never fully understand how it works.”