‘Strike team’ one strategy as insurers grapple with rapidly rising drug costs

If you’ve gotten a note from your insurance company explaining that you could be taking a different, cheaper drug, you may have Dan Danielson to thank.

Danielson, a pharmacist, leads a strike team inside Premera Blue Cross, one of Washington’s largest insurers.

His goal? To find the next EpiPen before it happens.

“We survey drug prices, specifically looking for drugs that are highly inflationary,” he said.

The EpiPen made headlines earlier this year when manufacturer Mylan bought the drug in 2007 and hiked the price 400 percent. Yet there are dozens of other drugs, from heartburn medication to diabetes treatments, that have soared in price during the past few years.

Danielson’s team monitors prescribing data and drug pricing to look for drugs that have jumped enough in price to hit the largest insurer in Eastern Washington with at least $50,000 in unexpected costs. That could range from a very common drug with a small price increase or a more rare treatment that’s quadrupled in price.

A drug arrives at Danielson’s desk about once every two weeks.

When the team flags a medication, they look to see if it has equivalents that are cheaper. Those could be generic drugs, drug combinations or just other brands that cost less.

“If there’s not a clinically appropriate alternative, there’s not much we can do,” Danielson said.

But if something else is effective for treating patients, Premera can do one of several things: They might require prior authorization for the more expensive drug or send a letter to providers letting them know that they can prescribe cheaper alternatives.

Kristin Parkes has been on the receiving end of a notification like this from Premera. She and her 2 1/2-year-old daughter, Lilly, both have Type 1 diabetes.

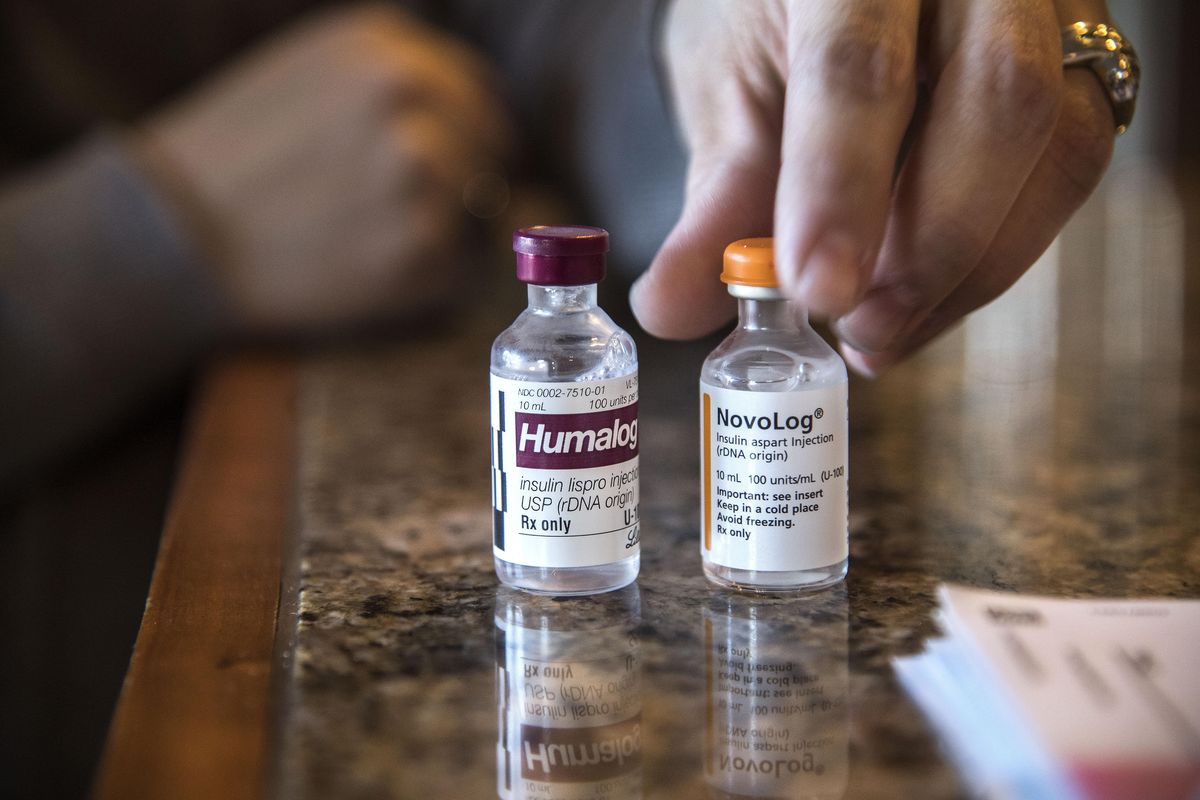

Because Lilly is so young and was recently diagnosed, her pancreas still functions partially. That means her insulin has to be diluted, so she uses Humalog, a brand that’s designed for dilution. The price of that insulin brand has climbed 21 percent over the past year, according to data from Medicaid.

“It’s the Oreo name brand of insulin,” Parkes said.

Lilly rarely goes through more than a fifth of a bottle before the insulin expires. To save the family money, Parkes had been using Humalog insulin so the extra medicine didn’t go to waste. But in September, Premera sent her a letter saying she would no longer be covered for Humalog.

That’s left the Parkes family with prescriptions for two brands of insulin, ultimately costing both her and Premera more. Every month, Parkes has to throw away Lilly’s mostly-unused insulin.

Parkes says she’s been working to get Premera to authorize her prescription for Humalog since she got the letter. Premera finally approved her request earlier this week after a Spokesman-Review reporter asked the company about Parkes’ case.

Melanie Coon, a Premera spokeswoman, said Parkes’ issue was in the process of being resolved before Parkes spoke to a Spokesman-Review reporter, though that may have expedited the process.

“There was some information that we didn’t have, and once we got the information, it was a done deal,” Coon said.

She said Premera can resolve some appeals in 72 hours and generally aims for 30 days or less. She’s not sure why Parkes’ issue took longer and said Premera wants to work with members in cases where drugs they need are denied.

“They can reach out and we can try to help them,” Coon said.

Even before the resolution, Parkes said she’s generally happy with Premera as an insurer.

“I don’t care how it got approved. I was just happy it was,” Parkes said.

But she’s noticed higher drug prices force patients to advocate for themselves more.

“As those prices go up you just have to fight harder with your insurance,” she said. “You spend a lot more time on the phone with your insurance explaining why they’re going to cover what you need.”

Insurers have always monitored drug prices and made coverage decisions based in part on the price of drugs. Parkes’ insulin was flagged through a normal drug pricing review cost, rather than the new effort to target highly inflationary drugs.

The companies have long argued that cost control in health care is the often overlooked part of health care reform, as most attention goes to health care access.

Premera’s effort is in response to what Danielson said is a new trend. Medium-size pharmaceutical companies that don’t do their own research and development will acquire smaller companies that have developed brand-name drugs for which there’s little competition.

“For lack of a better term, they’re investment tools,” he said. “They buy these drugs as if they’re just a straight commodity and then they increase the prices to whatever they think the market will bear.”

‘Really quick, really egregious’

Premera calls its new team SPRINT: the standing pharmaceutical cost response initiation team.

It started earlier this year after Premera noticed the price of Glumetza had spiked from $600 a month to $6,000 a month. The drug is a brand name version of metformin, a common drug to treat Type 2 diabetes.

Premera didn’t catch the price increase for several months, prompting internal calls to do better, Danielson said. Though they’ve always monitored drug prices and tried to steer customers toward cheaper options, the new team is specifically designed for price hikes that are “really quick, really egregious.”

When criticized for this behavior, pharmaceutical companies have typically responded with initiatives designed to lower out-of-pocket costs for customers – not insurers. Mylan offers coupons for up to $300 of the cost of EpiPens, making the drug more affordable for customers, and many companies have programs to provide drugs free or at reduced cost to low-income patients or patients without insurance.

Efforts like that make for better press, but they do nothing to alleviate the cost burden on insurance companies, who are stuck paying higher prices.

“The money that we are spending is coming out of premiums,” said Dr. Bruce Wilson, who chairs the committee that evaluates medications for insurer Group Health.

It’s worth noting that Group Health currently has a surplus of almost $957 million, according to financial documents filed with Washington’s Office of the Insurance Commissioner. Premera’s surplus is about $1.4 billion and has been climbing nearly every quarter since 2008.

Premera spokeswoman Melanie Coon said that surplus is intended to fund capital projects and give insurers more flexibility to deal with unexpected health care costs and claims. Premera began building up its surplus before the Affordable Care Act went into effect because the company knew it would be dealing with more cost unknowns, she said.

“The reserves are there for us to make investments to grow the business and also serve as a cushion when there’s a lot of volatility,” she said.

Premera lost almost $2.5 million in the third quarter of 2016, according to financial documents. Group Health lost $3.2 million in the same period.

Americans have dealt with double-digit drug price increases before. One of the things that’s different now, doctors say, is that patients are becoming more aware of the costs as insurance plans require higher co-pays and other out-of-pocket expenses.

“I recognize the insurers are getting squeezed. I think a big part of what they’re doing now is that cost is getting passed on to patients,” said Dr. Matt Hollon, clinical professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Spokane.

While drugs like the EpiPen get a lot of press coverage, less dramatic price increases are more the norm, he said.

“Those really egregious cases just represent the most dramatic cases of something that’s happening industry-wide,” Hollon said.

Government barred from price negotiations

Part of the problem, doctors say, is that there’s no check on pharmaceutical company pricing. Many other Western countries, including Canada, Norway and the U.K., pay significantly less for most drugs. That’s usually for two reasons: in single-payer health care systems, the government is by far the biggest, if not the only buyer of drugs. And in those countries, the government can negotiate drug prices, something Medicare is barred by law from doing in the United States.

That “basically means that drug companies can charge whatever they want,” said Dr. Robert Riggs, a family medicine doctor for Group Health in Spokane.

“The pharmaceutical industry is an extractive industry at this point. They are extracting money from America,” Riggs said.

Pharmaceutical companies have defended their prices by saying Americans are subsidizing research and development for the rest of the world. Without the high prices Americans pay for drugs, patients would lose access to certain medications and companies would be able to do less research and development.

Insurance companies negotiate drug prices and are often able to receive discounts because of their scale. Even before it was purchased by Kaiser Permanente, Group Health worked with them to negotiate discounts, Riggs said. But even large insurers and providers don’t compare to the size of the federal government.

“Until the government steps in … there’s nobody else that has the kind of leverage that the government has with the pharmaceutical industry,” Hollon said.

When patients can’t afford their drugs or get coverage, some go to their doctors to see if cheaper options are available. But sometimes, patients simply stop taking their drugs altogether or begin rationing doses.

Hollon said he has a patient whose wife recently lost her job. The patient has exhausted his insurance coverage for prescription drugs and has to pay for diabetes medication out of pocket.

“He’s having to ration his own insulin dosing because he can’t afford it,” Hollon said. “It’s really almost criminal that a country as wealthy as ours” can’t guarantee adequate health care, he said.

Dr. John McCarthy, the medical director for the Native Project, said he’s happy to write prescriptions based on which drugs a patient’s insurance will pay for. But he’s often unaware of how much a patient will pay out of pocket until they tell him.

“I can’t keep up with which one’s cheaper for which insurance,” he said.

McCarthy said he generally finds information from insurance companies helpful, since he’d rather prescribe something cheaper for his patients. But taking the time to go through a prior authorization process can be a hassle, he said.

“If we had a system that was easier and it didn’t take me a long time … to get prior authorization for all these medicines, it would make my life considerably easier,” he said.

Hollon said he and the providers he knows try to pick the most cost-effective medication for a patient.

“When we pick something other than a least expensive option, we’re usually doing it for a purpose,” he said. Requiring prior authorizations creates more work for him and his staff “to ultimately get the drug that we think is the right drug for the patient.”

Balancing patient needs, cost realities

Group Health hasn’t changed its practices for identifying cost-effective drugs in response to larger price hikes, Wilson said. Because Group Health is both a care and insurance provider, it’s easier for them to communicate information on cost to providers.

Riggs said he sometimes has patients come in and ask for a brand name drug because they’ve seen an ad for it on TV. He had a patient recently ask him about a drug to treat constipation caused by opiates. The cost was $1,600 per month, Riggs said, and Group Health wouldn’t cover it because generic drugs can treat the same issue.

“Sixteen hundred dollars for this drug when you can go to Rosauers and buy something that works for $10,” Riggs said.

Group Health has long focused on prescribing generic medications and gives patients lower co-pays for those drugs, Wilson said. The organization also doesn’t let doctors meet with pharmaceutical company representatives or give out drug samples to patients.

“When I was in private practice, I would get sold a new drug that came out and sometimes they’re really good, but they’re not 100 times better,” Riggs said.

As drug prices have climbed, Group Health has focused on increasing patient adherence by having pharmacists reach out to patients who are prescribed expensive specialty medication.

“We try to avoid the scenario where a patient may be embarrassed … go to fill a prescription, find out there’s no way they can afford it and forget about it,” Wilson said.

The Rockwood Health System has been communicating more with providers to let them know which drugs are more cost-effective. Keri Dobbin, a clinical pharmacist for Rockwood, said she’s found information from Premera very helpful in communicating to doctors.

“It’s hard to do anything without the actual data,” she said.

Side-by-side comparisons of drugs that treat the same condition but have vastly different costs have been especially helpful, she said. Patients sometimes don’t realize that FDA-approved generic medications have the exact same active ingredients as a brand-name drug.

“There’s this perception that a generic might not be as effective,” she said.

As costs are shifted to patients, Dobbin said she’s also seen patients more likely to stop taking medication or ration it, something Rockwood is working on improving.

For patients like Kristen Parkes who are managing chronic health conditions, higher drug prices mean more work, and higher out-of-pocket costs. Parkes says her family now counts on spending their $3,000 deductible every year.

And she plans to continue sharing the drug with her daughter.

“It’s very expensive life juice,” she said.