Before Spokane, the city of Twickenham was planned overlooking the river

In 1889, Spokane was nothing like it is today. Called Spokane Falls, it was a growing frontier town with too many wooden structures downtown and was at the very beginning of two decades of explosive growth.

The city’s founders saw this potential and intended to make money from it. That included Herbert Bolster. As one of the original 10 investors in the Washington Water Power Co., now called Avista, in 1889, Bolster had big plans for a city called Twickenham on a forested plateau overlooking downtown, which is now home to Spokane Falls Community College.

It was a suburban idea ahead of its time, considering what is now West Central was barely developed at the time. But Bolster believed in his plan. He platted Twickenham for 12 blocks for housing, built a baseball park and erected a wood and iron double-decker bridge to span the Spokane River at the west end of Boone. The top deck supported cable cars, the bottom a roadway for teamsters, horses and carriages.

Bolster had a good read on the future. He didn’t know it then, but Spokane was about to burst at its seams. When Twickenham was envisioned, less than 20,000 people lived in the city. Twenty years later, 104,000 did.

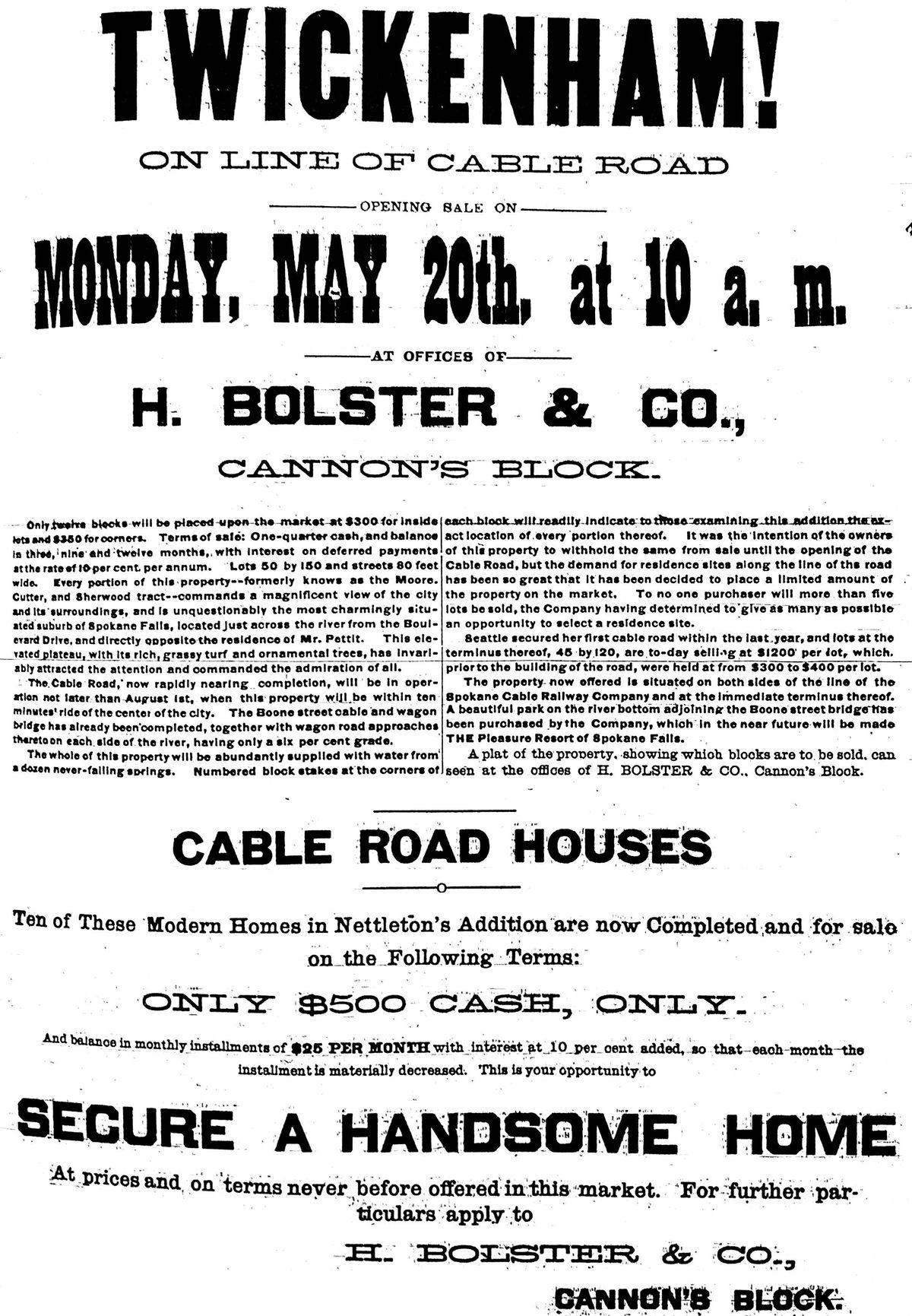

In May 1889, Bolster advertised his cable road houses in a flyer that screamed, “TWICKENHAM!” Most lots were $300, but corners went for $350.

“Every portion of this property,” the flyer said, “commands a magnificent view of the city and its surroundings, and is unquestionably the most charmingly situated suburb of Spokane Falls.”

Prospective buyers were invited to Bolster’s office at 10 a.m. Monday, May 20, 1889, a two-story wood building on the northwest corner of Riverside and Wall.

An article in the paper also boosted Bolster’s efforts, boasting of “the handsomest map that has yet been designed and executed by any of Spokane’s civil engineers.” It was reportedly a sideview profile of the development, showing the new “city,” the bridge and the streets. The main road was Twickenham while the others – Pall Mall, Belgrave, Burleigh, Roxbury among them – are “quite English you know.” The map was adorned with scenes from Twickenham’s future, including a “fairy cupid with a fish pale rampart” on the riverbank and an illustration of “the coaches and grip car that will run to Twickenham before the summer is over.”

It was not to be. Very few lots were sold and Holster’s office burned down that August in the Great Fire of 1889, presumably taking the “handsomest map” with it. The following year, the ballpark was disassembled and moved to the corner of Boone and A streets after Spokane became a charter member of the Pacific Northwest League, and the cable car ceased operation before ever carrying a passenger.

Five years later, a flood destroyed the bridge. Still in its native state, the land had a different future. Before the turn of the century, the federal government authorized funding to build a military fort, Fort George Wright, on the property. Decades later, it was turned into a college by the Sisters of the Holy Names convent and now hosts Mukogawa Women’s Academy and Spokane Falls Community College.