Spin Control: I nuked Spokane on paper for a story Wednesday. It was the second time in 36 years.

As a young reporter just a few months after joining The Spokesman-Review, I was called into the office of a top editor for an assignment.

We want you to tell readers what it would be like if a nuclear bomb hit Spokane, he said. Not to suggest it will happen, but paint a picture of “what if.”

This was 1981. Ronald Reagan was about six months into his presidency, the nation was building up its nuclear arsenal and hands on the “Doomsday Clock” kept by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists were moving closer to midnight.

Jonathan Schell was writing a series of articles for the New Yorker later to be turned into “The Fate of the Earth,” which would make the case that essentially nothing much would be left if the United States and Soviets started lobbing nukes at each other. Peace groups like Ground Zero were seeing a resurgence around the country and in Spokane.

Fairchild Air Force Base’s B-52s and their crews pulled round-the-clock ground alert, which meant the big bombers waited on the flight line loaded with nuclear weapons. The base was also being considered for the Air Force’s newest nuclear upgrade, the air-launched cruise missile. Fairchild had been on the Soviet target list for decades and might be moving up.

The Pentagon had a decades-old policy to neither confirm nor deny the presence of nuclear weapons at any given place at any given time. This was simply a “wink-wink” for Fairchild, because nobody thought those B-52s would stop somewhere else to load bombs after scrambling into the air when the klaxon sounded. At the time, the U.S. wasn’t planning on building cruise missiles that weren’t nuclear tipped. Putting a “conventional” warhead small enough for a missile with a $1 million price tag wasn’t considered cost-effective.

Stories about nuclear buildup were common, but missing from the daily news coverage was any significant explanation of what a nuclear blast could do.

As a veteran of duck-and-cover drills in grade school, I set out to nuke my new hometown on paper, intent not to screw up one of my first big assignments or make a mistake that my father, an aerospace engineer who spent his life designing military jets and missiles, would lecture me about.

I found experts who offered a best-guess on Soviet targeting strategy. The consensus was one detonation on the ground at the base, destroying the runway, the buildings and any planes still on the ground; another over the city, which would do somewhat less damage to the buildings, but be more lethal for the people.

While that seemed like overkill, both the Soviets and the U.S. had thousands of missiles, and once the first one was launched, the Soviets might decide they were in a use-it-or-lose-it situation.

They could do it with two well-placed one-megaton blasts, some experts said, but the Soviets had more five-megaton warheads on missiles and would likely go big because the guidance systems weren’t so accurate.

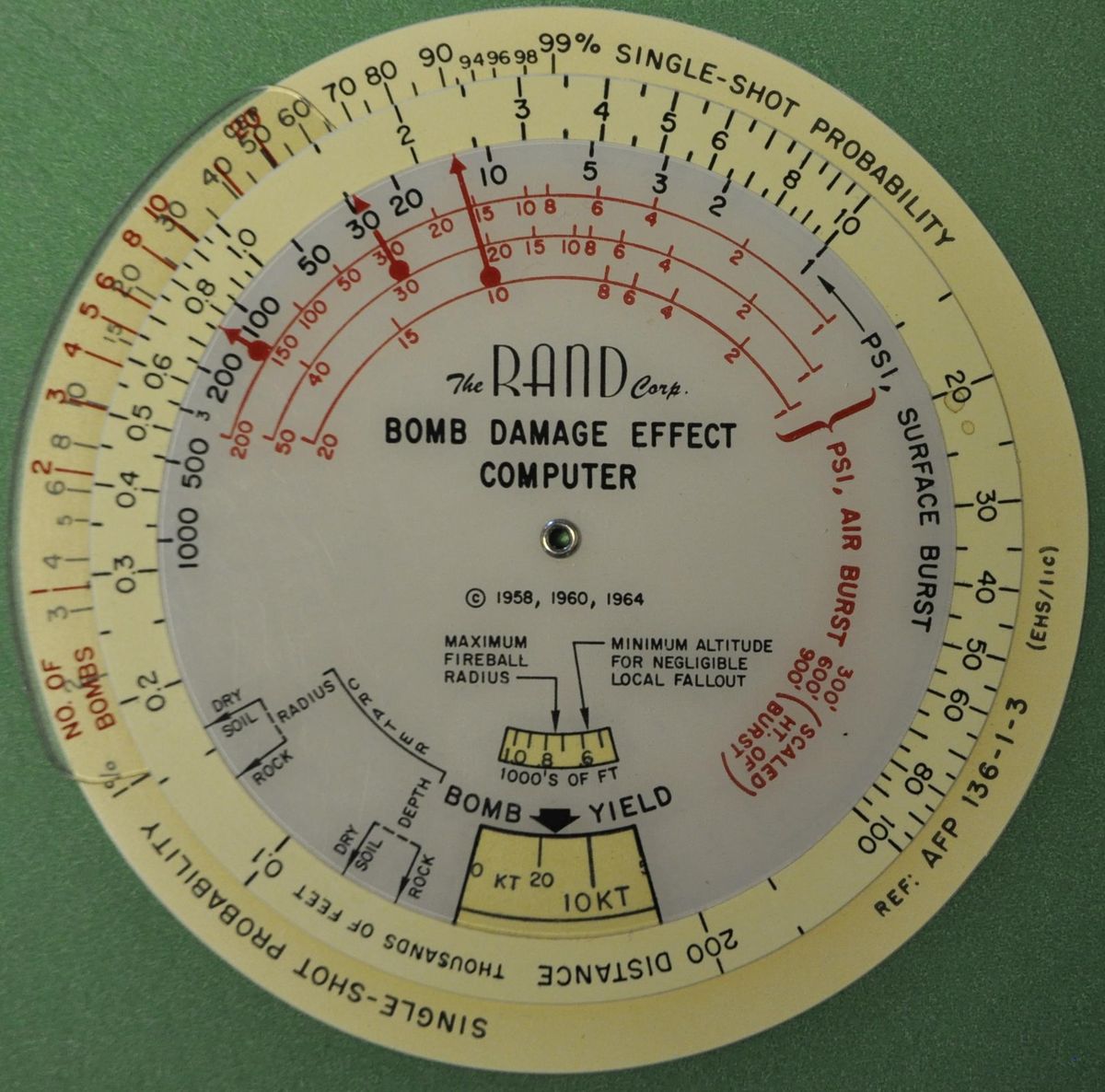

The best way to estimate the destruction of a nuclear blast in 1981 was with a Bomb Damage Effect Computer developed by the RAND Corp. over the previous three decades, the experts said. I called RAND hoping to get stats. Rather than running the numbers, the press office said they’d just send me one. Actually, they sent me two, the basic model from the 1950s and their brand new version.

These aren’t computers like today, with a keyboard, screen and chips in circuit boards. They are proportion wheels: plug in the size of the warhead and it will estimate the size of a crater, the radius of a fireball and the distance at which the air pressure will be so powerful as to knock down buildings after the explosion. The new models made adjustments for other types of damage. Let’s just say all of it was grim.

I drew circles on a map of Spokane, and wrote down what would happen. The story, with a picture of a mushroom cloud rising over downtown buildings, ran on the front of a Sunday Perspective section the paper had at the time for commentary, analysis, editorials and letters to the editor. Some readers accused The Spokesman-Review of scaremongering to sell papers; others said they found it interesting and informative for the time we were living in.

I told the former that “scaremongering” wasn’t the intent and the economics of newspapers don’t work that way, and thanked the latter.

Fast-forward to this summer, with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un testing missiles and President Donald Trump offering to respond to any future threats with “fire and fury.” When news accounts said the latest North Korean ICBM could reach Seattle or San Francisco – and by geographic interpolation Spokane – they focused on the politics and strategy, skipping over details of what a blast could do.

Because I rarely throw away interesting stuff from stories, I asked the editors if they wanted me to pull out the Bomb Damage Computer and write about what that might look like.

After an explanation of what the heck I was talking about, they said yes. Not to say it will happen, but to paint a picture of what if.

The calculations from 1981 had to be completely redone, because the North Korean bomb is thought to be no larger than 12.5 kilotons, making it about 400 times smaller than the ones calculated for a Soviet strike.

I needed a refresher course on the Bomb Damage Computer. Unfortunately anyone who knew how to use one was long gone from the various think tanks and peace organizations. Even RAND couldn’t produce someone familiar with their tool.

But because this is 2017, there is a program on the internet called NukeMap that makes some of the same calculations which allowed me to check things the wheel seemed to be telling me, and add casualty estimates. Again, the details were grim, even leaving out some effects mentioned in the original story.

I was able to devote the top half of this story to some discussion of what may be hype over the North Korean missile launches. Some people who know this kind of stuff – physicists and engineers – doubt those missiles can go as far as the Pentagon suggests, and wonder if they can even re-enter the atmosphere without burning up.

That story was on the front page Wednesday, the day after North Korea’s latest missile test. The color photo of a fireball and mushroom cloud over the Spokane landscape might’ve caught some readers’ attention.

Some readers who called or wrote in recent days accused The Spokesman-Review of scaremongering to sell papers or get clicks online; some have said they thought it interesting and informative for the time we’re living in.

So some things changed in 36 years; other things are about the same.