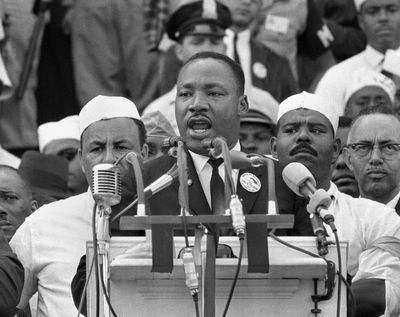

Examining Martin Luther King Jr., in the momentous years after ‘I Have a Dream’

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was human, not a saint, though many insisted on placing him on that dangerous pedestal, and do still, 50 years after his death. As one character in August Wilson’s ’60s-set play “Two Trains Running” says, bluntly: “When you get to be a saint there ain’t nothing else you can do but die.”

The years following King’s 1963 march on Washington, D.C., culminating in his deathless “I Have a Dream” oratory, were painful and difficult. In a 1967 interview, the year before he was assassinated in Memphis, the activist and enemy of the FBI acknowledged that “at many points” during those years, the dream he spoke of had “turned into a nightmare.”

This week marks the 50th anniversary of King’s murder, an act committed April 4, 1968, by white supremacist and Alton, Ill. native James Earl Ray. King had lived with violence and death threats for years. He battled spiritual and physical exhaustion; his precepts, methods and conciliatory activist impulses created as many enemies as supporters, even within his own ranks.

On Wednesday Paramount Network debuts “I Am MLK Jr.,” one of three new and historically intertwined nonfiction commemorations of King’s life and legacy. Back in rotation on MSNBC, the two-hour “Hope & Fury: MLK, the Movement and the Media” premiered late last month on NBC. On HBO, meantime, the excellent “King in the Wilderness” began airing earlier this week.

The “final founder of American democracy”: That’s what author and CNN commentator Van Jones calls King in co-directors John Barbisan and Michael Hamilton’s “I Am MLK Jr.” The documentary is an absorbing if scattershot 90 minutes; King, of course, will remain an inspiration in perpetuity.

The film connects the 1956 Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott and other, later acts of civil disobedience to the modern day. Footage of King meeting with high school students after he wrote his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” manifesto speaks directly to today’s images of the Parkland school shooting activists, facing stiff opposition from the gun lobby. The minister’s son said it: There is a time “when the cup of endurance runneth over.” That time, whatever the issues, remains forever present.

“I Am MLK Jr.” relies on various contemporary African-American figures, from actor Nick Cannon to NBA all-star Carmelo Anthony to the ubiquitous Jesse Jackson. Some, like Jackson, were King’s associates; others are simply among those inspired by King’s legacy of hope against hope, and action against equal and opposite reaction.

Georgia congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis was 15 when the Montgomery bus boycott got underway. King “inspired me,” he says, “to find a way to get in the way.”

There are times when the documentary gets in its own way, settling for broad strokes and testimonials of a predictable sort. Far better, and using some of the same talking-head interview subjects to fuller, more persuasive advantage, is the two-hour documentary “King in the Wilderness,” now on HBO.

Director Peter Kunhardt’s moving account of King’s darkest hours allows us glimpses of a King we may not have seen, or known. It’s not easy to watch the footage, even with King’s words and actions as ballast. The fire hoses. The wiretappings. The white rage, much of it concentrated in Chicago, when King came here to protest housing discrimination. In a few sharp, incisive minutes, “King in the Wilderness” captures a city ruled by Mayor Richard J. Daley’s jobs-for-votes patronage and Chicago’s long-standing ethnic divisions.

Attorney, adviser and King confidante Clarence Jones appears in both “King in the Wilderness” and “I Am MLK Jr.” In “Wilderness,” he speaks eloquently of how the Chicago project shook King’s confidence and rattled his belief in the country’s receptiveness to change. All those boys in crew cuts, carrying signs with swastikas, lining up in Gage Park next to young men and women carrying “We want Wallace” signs – it was sobering.

“I’ve seen some hate-filled eyes and mouths in Mississippi and Alabama,” Jones says in “Wilderness.” But “the hate I saw in Illinois was equal to or greater than any of the hate I saw in Mississippi.”

“King in the Wilderness” makes great use of King’s friend and supporter Harry Belafonte, a first-hand witness to history. “I Am MLK Jr.,” for better or worse, focuses more on younger African-American figures explaining to a different audience what King’s legacy means to them in 2018. In both documentaries, the backroom and public strategies and beliefs of presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson cannot help but directly rebuke our current president’s engagement (or refusal to engage) with the roiling world around him. Kennedy invited all the key March on Washington speakers to the White House; Johnson, a more conflicted leader, nonetheless muscled through civil and voting rights legislation. What if they had been in office when the Parkland students spoke out? Would they have favored the activists’ side of history, or the opposition’s?

Only a figure as large and enduring as King can inspire such speculation. He framed and clarified so many moral and constitutional issues in his short lifetime. He “shook the world,” as Jackson says, twice, in “I Am MLK Jr.,” the second time with incremental, awestruck pauses between the words “shook,” “the” and “world.”

“I Am MLK Jr.”

8 p.m. Wednesday, Paramount Network