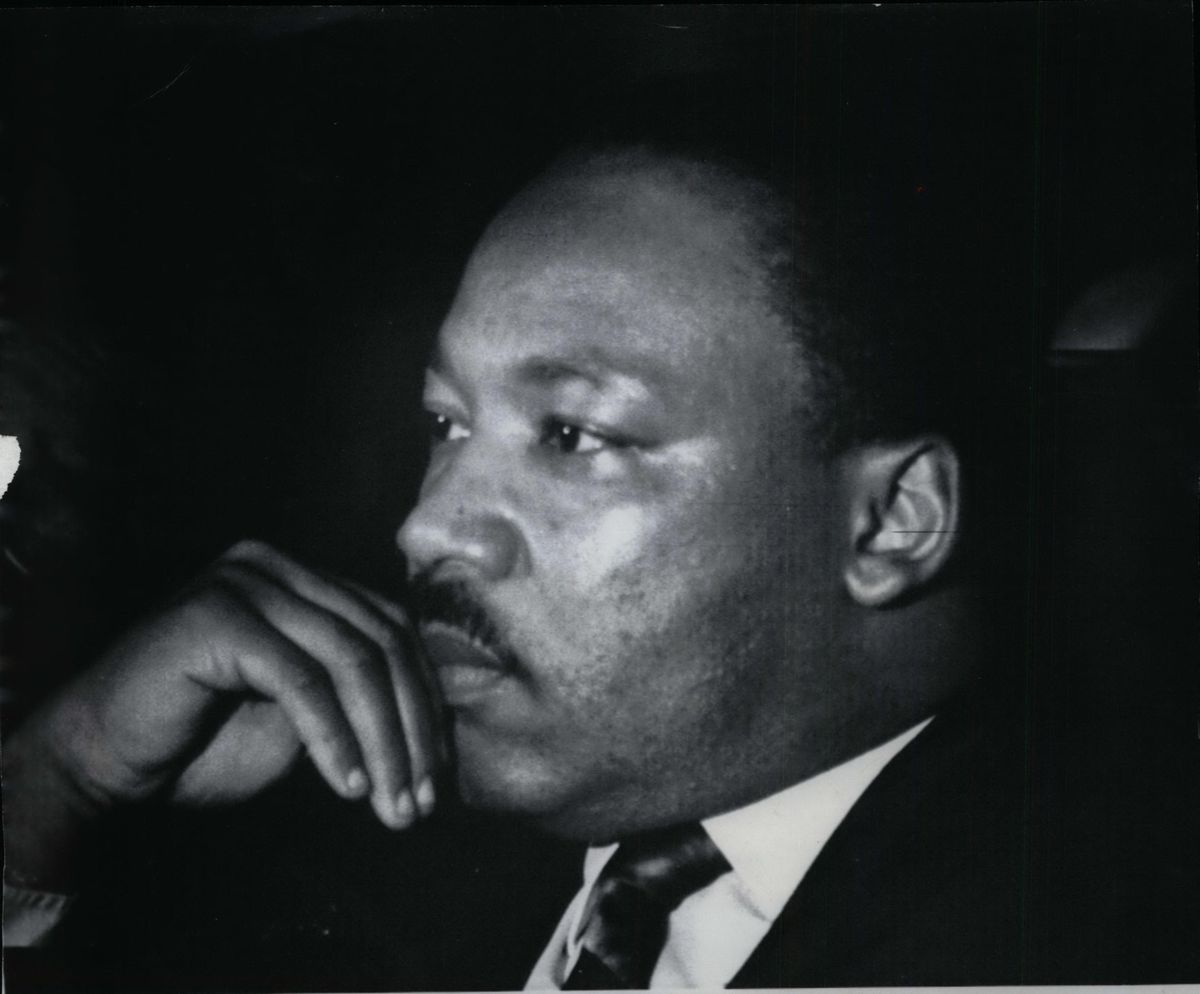

50 years after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Spokane civil rights leaders say his lessons more relevant than ever

It’s been 49 years, nine months and nine days since Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated outside of his hotel room in Memphis, Tennessee.

Some of Spokane’s longtime civil rights leaders say they can still hear his booming voice playing over and over in their minds. They still remember the joy and reverence he shared with them through a TV screen or over the radio; they remember the heartbreak of April 4, 1968.

At a moment when divisive policies and rhetoric appear resurgent, they say, Dr. King’s accomplishments in uniting the country across racial lines have never been more crucial.

When word of his death spread, the Rev. Walter Kendricks of Morning Star Missionary Baptist Church was at a Boy Scouts meeting outside of Cleveland, Ohio. He was 11. His scoutmaster had just led the troop through the Boy Scout oath.

“He said, ‘This might not mean a lot to you, but the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King has been assassinated,’ ” Kendricks remembered. “Those were his words.”

Each year in the middle of January, people like Kendricks gather and remember together. At churches across the city they talk about King’s legacy, his dreams cut short. They discuss his grand ideas, what he would do today if he were alive. And they reflect and preach on four decades of civil rights, progress, inequality, racism, respect and fear that have followed since his death.

This year, in Spokane and elsewhere, the talks are more intense than ever. In 2017, white nationalists felt emboldened enough to hold a rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Locally, racist flyers and propaganda were posted in downtown Spokane and Sandpoint, Idaho. Self-avowed white supremacists are alleged to have stuck a gun in an elderly black man’s face and threatened his life.

Many civil rights leaders point to the election of President Donald Trump – following a campaign dominated by protectionist rhetoric and verbal attacks on immigrants and minorities – as a catalyst, or perhaps the most visible manifestation of a possible new chapter in the country’s troubled history with race. Just last week, new language from the White House disparaged immigrants from predominantly black countries, drawing national and international criticism.

For Kendricks and others, it can feel like King’s message has been lost in the noise, especially in a 24-hour news cycle in which sound bites often overrun measured dialogue.

“It’s a mixed bag,” Kendricks said. “We’ve made progress in some areas, but in many, many other areas we’ve actually regressed instead of progressed.”

‘(B)and together’

On Sunday, the day before thousands are expected to gather downtown and march in King’s name, local religious leaders led their congregations in prayer and worship before convening at the Holy Temple Church of God in Christ to formally remember and celebrate the late reverend.

The Rev. Percy “Happy” Watkins, whose rendition of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech has captivated thousands over the years in the Inland Northwest, spent the morning with a few dozen churchgoers at the New Hope Baptist Church in Spokane Valley.

At 75, he’s reduced the number of speeches he gives in the weeks and days leading up to his hero’s holiday. But that didn’t stop him from talking at Freeman High School on Friday, where he said it was “heartening to see those young kids being strong” months after four of their own were shot in the halls by a student in September.

At his church Sunday, after a sermon delivered by his son, Watkins recited the speech word for word from memory. At each inflection, he embraced cheers and words from the crowd. At each pause his smile widened.

While he’s been delivering the speech for more than 30 years, he said this year feels the most necessary.

“One of his great announcements was love,” he said of King. “I say that because all of a sudden now we’re seeing a rise in racism. I think he would tell us to band together. He would tell us to work together to make a difference until making a difference don’t make a difference no more.”

A message for everyone

For Ken Stern, a founding member of Gonzaga University’s Institute of Hate Studies advisory board, 1968 was a year of converging forces.

“It seemed like all of the issues that had been on the rise were suddenly coming to a head,” he said. “And where they came to a head, there was a cultural clash.”

Stern, who serves as executive director of the Justus & Karin Rosenberg Foundation in Brooklyn, was only 15 at the time – younger than most of the activists, students and protesters taking to the streets. But the day after King’s assassination, a teacher confronted him with a question that, he said, has stayed with him ever since.

“He asked us, ‘If Dr. King were alive, would you be marching with him today?’ ” Stern said. “A couple of us raised our hands. And he says, ‘He was alive yesterday. Why weren’t you marching then?’ ”

That question, and the tumultuous events of the era, helped steer Stern toward law school and a career in civil rights litigation, including a successful decade of defense of Dennis Banks, an original founder of the American Indian Movement, against the U.S. government. Over the decades, he said, racial divisions and the parties that would widen them have always been present – though not always blatantly so.

“There’s always hatred at work in the world. The question is, does it exist in the extremes – is it marginalized – or does it enter the mainstream?” he said. “To me that’s one of the greatest questions. And it worries me that we’re seeing a time when it has gotten a lot of oxygen from the mainstream.”

Divisive rhetoric from the country’s highest office stokes a capacity for distrust and division that exists in all people, he said – the very capacity that Martin Luther King Jr. was working against.

Dr. King succeeded in bridging boundaries “because his message was for everyone,” he said. “He was talking to me, a white Jewish 15-year-old in New York City. He was talking to people in black churches. He was talking to what this country is meant to be – a society that is inclusive to all Americans.”

Navigating a new terrain

In the same year that a racial divide has seemed to engulf the country, Kurtis Robinson was tasked with helping put it back together – at least in Spokane. As the president of the Spokane chapter of the NAACP, Robinson admits there’s a “deep contrast” happening in American politics, with no discernible end in sight.

“I don’t think we’ve ever been here before,” he said. “We’ve never had this many people in the country before, on the planet before. We’ve never had the social media availability that we have now. I think in that context, it’s definitely a new place.”

The answer might be in the next generation. Robinson said one of the goals for the NAACP in 2018 is to focus heavily on youth engagement, something that he said has been lacking in the past.

By reaching out to local colleges, including Gonzaga University, Washington State University and Whitworth University, he hopes to engage students and push for a more socially active minority population of Spokane.

It’s something he thinks King would do. If he were alive today, he theorizes the reverend would be quick to address racism and strip it down to its core, which Robinson equates as “the extension of classism, and even further than that, the capitalistic classism.”

“He would be very focused on addressing the poverty dynamics of that system,” Robinson said.

Watkins agrees but said he thinks King would first try to bridge social and political divides. After all, that was one of the core messages in his famous speech, which Watkins has studied for 35 years.

While he plans to keep going in the years to come, Watkins said he hopes one day the speech will fall on a different set of ears – ones that don’t recognize the racism and inequality King so passionately spoke against. Ones that have no idea what it was like to live as a black person in the 1960s, or for that matter, in 2018.

“I still have a few more dreams before I close my eyes,” he said. “I’m going to take my time. We’ll see.”

Assistant City Editor Nathanael Massey contributed to this report.