Inslee talks trade, Trump at town hall in Spokane

Gov. Jay Inslee landed a few zingers against President Donald Trump, including one about the administration’s trade policies and their effects on Washington agriculture, during a town hall event hosted by The Spokesman-Review on Monday evening.

In response to a question about the administration’s $12 billion aid package for the U.S. agriculture industry, an attempt to cushion farmers from a trade war spurred by tariffs on Chinese imports, the Democratic governor characterized the plan as “hush money” – a thinly veiled reference to payments made to an adult film actress, Stormy Daniels, and a Playboy model, Karen McDougal, who claim they had affairs with the president.

“One of the things I’m sure the president does not understand is that markets take years to develop, and once you lose them, it takes you years to get them back. You just don’t turn this switch over if you ever do get some kind of deal,” Inslee said. “So you can call this a bailout, but when you look at the style of Donald Trump, it’s more kind of hush money, to try to calm down the voices that we are hearing. It is not going over well.”

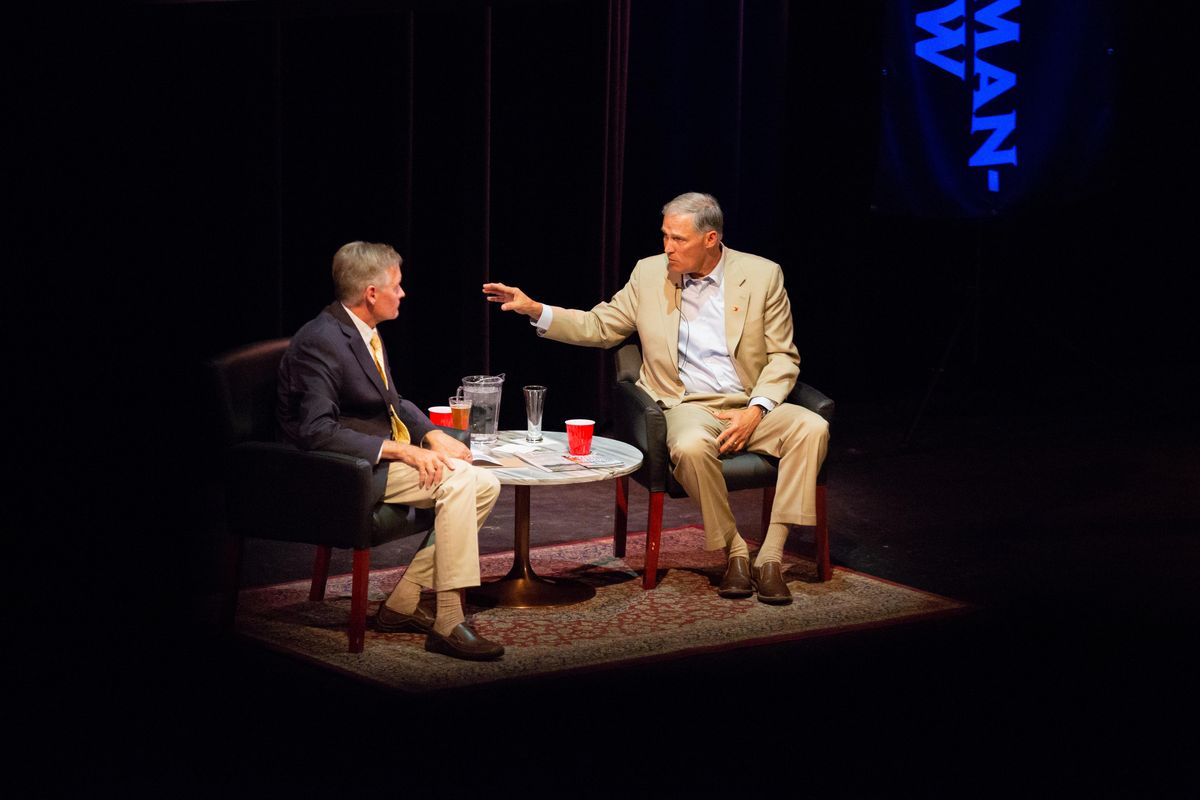

Inslee’s remarks came during the latest Pints and Politics event hosted by the newspaper’s Northwest Passages Book Club at the Spokane Civic Theatre. After a round of questions from veteran political reporter Jim Camden, the governor took questions from the audience. Topics included public education, mental health care, immigrant asylum-seekers and the environment, as well as regional issues such as a proposed silicon smelter in Newport that has raised concerns about air pollution.

On the agriculture bailout, Inslee said that farmers want “trade, not aid” and that Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods were a bad move to begin with.

“The right way to go is to not blow up the farms in the first place,” he said. “I had a meeting in Yakima … just a few days ago with the fruit industry, and they’re just getting hammered. We’re shut out from the Chinese market. We’re shut out from the Indian market of apples and cherries. We actually have fruit on ships today in the Pacific Ocean going with no place to go right now. And people are already – business people have told me that they’re deferring investment decisions.”

The situation also has caused problems for Washington’s manufacturing industry, he said.

Now that the Legislature has met the requirements of the McCleary decision – the controversial 2012 ruling by the state Supreme Court that mandated billions of dollars in increased spending on K-12 education – Inslee said it’s time to focus on higher education programs such as the State Need Grant, which enables many of Washington’s poorest students to attend college but has not been able to benefit all eligible students who apply.

A supplemental budget passed by the Legislature in March adds $18.5 million to the State Need Grant through mid-2019, a boost that is expected to clear up three-fourths of the waiting list of approximately 4,600 students and put the program on track to cover all eligible students by 2022.

“The first job is to make sure that every student that is in need of a scholarship gets it,” Inslee said.

He also said he wants to change the K-12 system to focus not only four-year college preparation but also on job training programs, apprenticeships and two-year degrees. He lamented that the average age of students in Washington’s technical colleges is 28, meaning there’s a 10-year gap from the time they graduate high school.

“I believe we need to restructure fundamentally our educational system so that we stop telling our children that if you don’t get a four-year degree you’re a failure in life. We need to stop telling them that,” he said. “If they want to go to our two great medical schools in Spokane, great. If they want to be a physicist, great. But if they want to be a journeyman electrician and help build the new system of clean energy we’re going to build in the state of Washington, that’s great too.”

In May, Inslee announced an ambitious – and costly – proposal to overhaul the state’s mental health care system. More patients would be treated in small, community-based treatment centers while Eastern State and Western State hospitals, which have grappled with overcrowding for years, would be used mainly for forensic evaluations.

“The way we have been providing services today, of very large institutions, just really is antiquated,” Inslee said. “It just doesn’t fit the current science of how you provide mental health.”

While he acknowledged that building new treatment centers in cities may be unpopular with some neighbors, Inslee said he believes the idea has bipartisan support.

“Both Republicans and Democrats understand that if you provide health care in a community-based setting, it is more effective because the people are closer to their families, they’re closer to their churches, they’re closer to their jobs,” he said. “It just works better.”

Asked about the ongoing opioid crisis, Inslee spoke of Washington rules that aim to curb overprescribing and of efforts to promote naloxone, a drug increasingly carried by police, firefighters and emergency medical personnel that rapidly reverses opioid overdoses. He then pivoted to efforts by congressional Republicans and the Trump administration to repeal and weaken the Affordable Care Act.

“At the same time we have an opioid crisis, where every politician in America has at least given lip service to this, there has been an effort to totally take away health care from 800,000 people in the state of Washington,” he said.

Inslee also lambasted the Trump administration for its recently discontinued policy of separating children from parents seeking asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border, calling it “one of the cruelest things I’ve ever seen in my life.”

“This was not an accident,” Inslee said. “This was an intentional decision to inflict pain on young people and their parents. And I don’t like the thought that we have a president who wakes up every morning trying to figure out how to inflict pain on young kids.”

Inslee, whose second term as governor ends in 2020, fueled speculation that he’s considering a presidential run when he spoke last month at a Democratic fundraiser in Iowa, the home of the nation’s first primary caucuses. But he again demurred when asked about his political aspirations Monday evening.

“I’m really focused on 2018, and I’ll tell you this: I know people are concerned about 2020, but we cannot wait ‘’til 2020,” he said, noting that he has worked with other Democratic governors to tackle climate change and other issues. “We have to rescue the country as soon as we can.”