This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

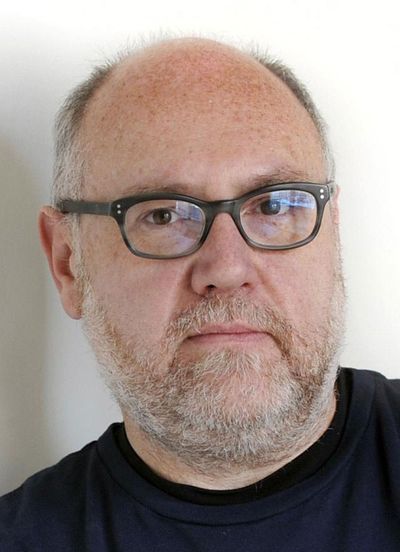

Shawn Vestal: It’s time to let the death penalty perish for good

Let it die.

The death penalty has had a long, troubled life in Washington, serving vengeance more than justice. It’s already on life support from a gubernatorial moratorium, and it’s time to let it perish.

The state Supreme Court has again found that the death penalty, as Washington has applied it, is unconstitutional. It’s the fourth time the court has so ruled, and each previous time Washington citizens and lawmakers followed up by trying to “fix” it and keep killing criminals. A lot of us are very committed to the idea.

But with this week’s fourth strike – based in part on evidence that black defendants were around four times more likely to be sentenced to death than similarly situated white defendants – we should exercise the collective wisdom to abandon the death penalty for good.

We don’t need initiatives or legislation. Let’s just get it a gravestone.

The case history of Washington’s death penalty, as laid out in the unanimous opinion of the court on Thursday, illustrates that it is well-nigh impossible to apply fairly, doesn’t work as a deterrent and consistently – despite several attempts to surmount the problem – violates the constitution.

Still, the justices emphasized that their opinion applies only to the death penalty as Washington has applied it. Some other, so-far-unspecified system of capital punishment might still be constitutional.

“We leave open the possibility that the Legislature may enact a ‘carefully drafted statute’ … to impose capital punishment in this state, but it cannot create a system that offends constitutional rights,” the justices’ opinion says.

To do that, it must be “properly constrained to avoid freakish and wanton application,” the justices wrote, quoting a 2006 precedent, State v. Cross.

The history of Washington’s attempts to do this suggests that may just be impossible. Freakish and wanton are this penalty’s middle names.

Racial disparities are a major part of this. A report prepared for the defendant in the case, Allen Eugene Gregory, showed that black defendants are much more likely – by between 3.5 and 4.6 times, depending on the model – to be sentenced to death than white defendants convicted of the same crimes.

By itself, that would be far more than sufficient grounds to throw it out.

But Justice Charles Johnson, writing a concurrence on behalf of four justices, laid out another example of the capricious application of the death penalty in Washington state: Some counties seek and impose it, and some do not. Effectively, the death penalty only exists in a few counties.

A 2006 report by the Washington State Bar Association concluded that since 1981 there had been 254 aggravated murder cases eligible for the death penalty. But the penalty was only sought or imposed in 17 of 39 counties with such cases, and only imposed in 10 of those counties.

Of the 30 death penalty cases imposed by those 10 counties, the report concludes, 19 were reversed on appeal and “nearly all have resulted in a sentence of life without the possibility of parole.” Five executions have been carried out.

Reversals outnumber executions almost 4-to-1.

As the death penalty has become rarer in Washington state, this geographical disparity has only increased, Johnson wrote. Since 2000, only three prosecutors have sought the death penalty, and in only two counties was it imposed.

“Where a crime is committed is the deciding factor,” Johnson wrote, “and not the facts or the defendant.

“Based on this report and what additional information we now have, it cannot be said that trials resulting in death sentences are reliable. Where the vast majority of death sentences are reversed on appeal and ultimately result in life without parole, reliability and confidence in the process evaporates.”

By this point, confidence in the death penalty should be completely evaporated. The problems with the death penalty are baked into its very nature, and the notion that we can work around them is a fool’s errand.

Each time we’ve tried, we’ve failed. Time to stop trying.