Spokane Transit’s Central City Line wins $53.4 million in federal money, fully funding the project

Twenty years after the idea was first hatched, and more than two years after voters signaled approval for the project, the federal government has allocated $53.4 million for Spokane’s first bus rapid transit line.

Now fully funded, the streetcar-like, fixed-route, zero-emission bus is scheduled to begin running through the city’s core in 2021, connecting Browne’s Addition with Spokane Community College on a 6-mile loop. The federal grant also will purchase 10 low-emission electric buses for the Spokane Transit Authority.

Spokane County Commissioner Al French, who has been in local politics almost as long as the idea for such a transit line began circulating in 1999, said the Federal Transit Administration awarded the money due to the “creativity” of Spokane’s system, which will look and operate something like a train but run on rubber tires.

“We have a very creative project. One of the first of its kind in the country,” said French, who sits on STA’s board of directors. “It’s the midpoint between having a sleek, upscale – and very expensive – light rail system, and a bus. If you go to Europe, you can see these kinds of vehicles, but they haven’t been able to gravitate to the states yet.”

The money appropriated on Tuesday comes from an FTA Small Starts grant, which is part of a larger program that allocates about $2.3 billion in funding every year for all kinds of transit projects including commuter rail, streetcar and bus rapid transit. Tuesday’s grant award funded 16 projects with $1.36 billion.

With the federal grant, the $72 million project is effectively fully funded. The last share of dollars is expected to come later this month when state legislators will award $11.4 million to the project, the last of $15 million the state promised in 2015.

In a joint news release, U.S. Sens. Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell, and Congresswoman Cathy McMorris Rodgers, praised the project.

McMorris Rodgers, the sole Republican and only resident east of the Cascades among the three lawmakers, applauded the anticipated economic benefits the federal allocation may bring to the city.

“This is great news for everyone in Spokane,” she said in a statement. “Not only will the full grant funding of the Central City Line help further connect Spokane with the surrounding areas and provide reliable public transportation services to the entire community, but it will also bring an estimated $175 million in economic impact here in Eastern Washington.”

Murray, a senior member of the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee, called the project “forward thinking” and said she would make sure that “transportation and infrastructure priorities for families east of the Cascades remain top of mind in the other Washington.”

Cantwell, the top Democrat on the Senate’s Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee, hailed the line’s high frequency, which will run every seven-and-a-half minutes during weekday rushes.

Light rail to trolley to BRT

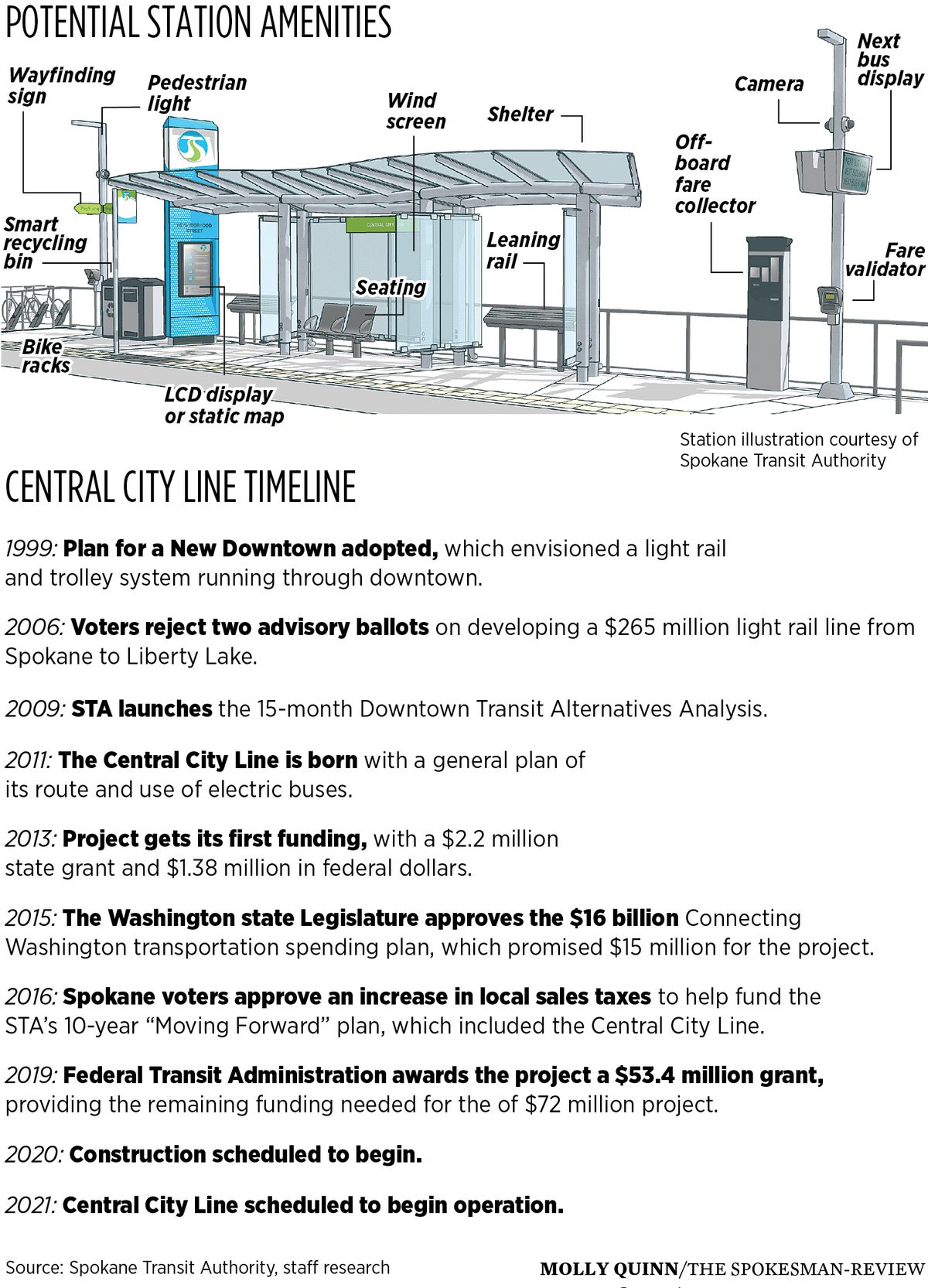

The idea that eventually became the Central City Line began in 1999, with the Plan for a New Downtown.

The plan, part of the larger city comprehensive plan that guides development, envisioned a light rail system running from the east side of town along Riverside Avenue, through the University District and terminating at the STA Plaza. At the same time, the plan described a complementary trolley system with an east-west line running from Browne’s Addition to the University District.

As the outsized costs of such a transit plan were realized, it was scaled back again and again.

In 2006, voters were asked to consider the construction of a light rail between the airport and Liberty Lake, estimated at $265 million. They rejected a pair of advisory ballots on developing the line, forever deferring the project.

The desire for a modern transit system downtown didn’t die, however, and in 2009 STA began discussing a system much scaled down from the light rail proposal. At the time, officials floated the possibility of a streetcar system, or electric trolley buses powered by an overhead wire. Using $360,000 in federal and state grant funds, the agency began a 15-month Downtown Transit Alternatives Analysis.

In 2011, what is now known as the Central City Line was born. The analysis had shown a preference on a general route for the line. An early idea to run the line as a trolley was ultimately jettisoned in favor of battery-powered electric vehicles.

In 2013, the project’s first funding came with a $2.2-million regional mobility grant – state dollars intended to improve transit and reduce traffic congestion on heavily traveled roads. Months after that grant, the project secured $1.38 million in federal money aimed at projects that meet requirements of the Clean Air Act.

In July 2015, the Washington Legislature passed the $16 billion Connecting Washington transportation spending package, which promised $15 million for the Central City Line. The next year, in November 2016, 56 percent of Spokane voters approved an increase in local sales taxes to help fund the STA’s 10-year “Moving Forward” plan, which included the Central City Line.

“We’ve been at this for quite a while,” French said. “But with every step of the evolution of this, it’s gotten better. We would never have been able to envision in 2001 the system we’re going to put in place.”

BRT is inexpensive, popular

The system is called bus rapid transit, which is becoming a more common, and relatively inexpensive, way for cities to build modern transit systems. According to BRTData and the Institute for Transportation & Development Policy, there are 170 cities worldwide with such systems, 13 of them in U.S.

Latin America – which includes Mexico, Central America and all of South America – has the most BRT lines with the most passengers of any global region, with 55 city systems carrying 20.5 million passengers a day.

While Spokane’s upcoming system is technically BRT, it has been criticized for missing some key features, most notably a dedicated lane for the line where other vehicles can’t travel. Such a lane would keep the bus out of congestion and ensure the rapidity of the line – something integral to its identity, as the name suggests.

Another element – giving the bus priority at traffic signals – isn’t part of the line’s full route. Three of the five signals on the line outside of downtown may have that feature, which would have the signals turn green when the bus approaches.

Otherwise the buses will look and act very differently from what Spokane residents see today.

Passengers will purchase fares at kiosks before boarding, doing away with the line of people slipping crinkled dollars into the fare box when they board, and shaving off seconds and minutes at each stop. The system’s 21 stations will be level with the bus door, allowing for quick and easy boarding. The bus will have multiple doors for entering and exiting, again limiting any queuing passengers may do.

Perhaps most importantly, the bus will provide frequent service through the city core until 11:30 p.m., including running every seven-and-a-half minutes during rush hour, and 10- to 15-minute service for the rest of the day and on weekends.

The system is anticipated to draw 4,100 daily trips by 2035, and 1.2 million annual trips. The annual operating cost is estimated to be $4.6 million. An economic analysis of the project done in 2014 estimated that property along the route would gain $45 million in value, and lead to $175 million in improvements done to the land, over the next 30 years.

The federal grant funding the Central City Line also funded four other BRT projects in the country: the 13-mile First Coast Flyer Southwest Corridor Bus Rapid Transit project in Jacksonville, Florida; the 1.8-mile Virginia Street Corridor BRT project in Reno, Nevada; the 16-mile River Corridor-Blue Line BRT project in Albany, New York; and the 15-mile Division Transit BRT project in Portland, Oregon.

The federal money wasn’t expected in Spokane until later this year, and could put the project on the fast track. But there’s still work to be done, including the construction and getting the buses made and delivered. Since the project is federally funded, the 60-foot, articulated buses have to built in the U.S.

“This decision steps us up a full year in our schedule. We still have to do the construction and we still have to get the buses made and delivered,” French said. “But it certainly gives us an opportunity.”