Jerry Gardner, longtime Cheney police chief who inspired a novel, dies at 78

Jerome “Jerry” Gardner started his law enforcement career as a patrol officer in Southern California in the 1960s, confronting gang violence and riots against police. He told stories of suspects throwing Molotov cocktails and shards of glass and holding a double-barreled shotgun at his neck.

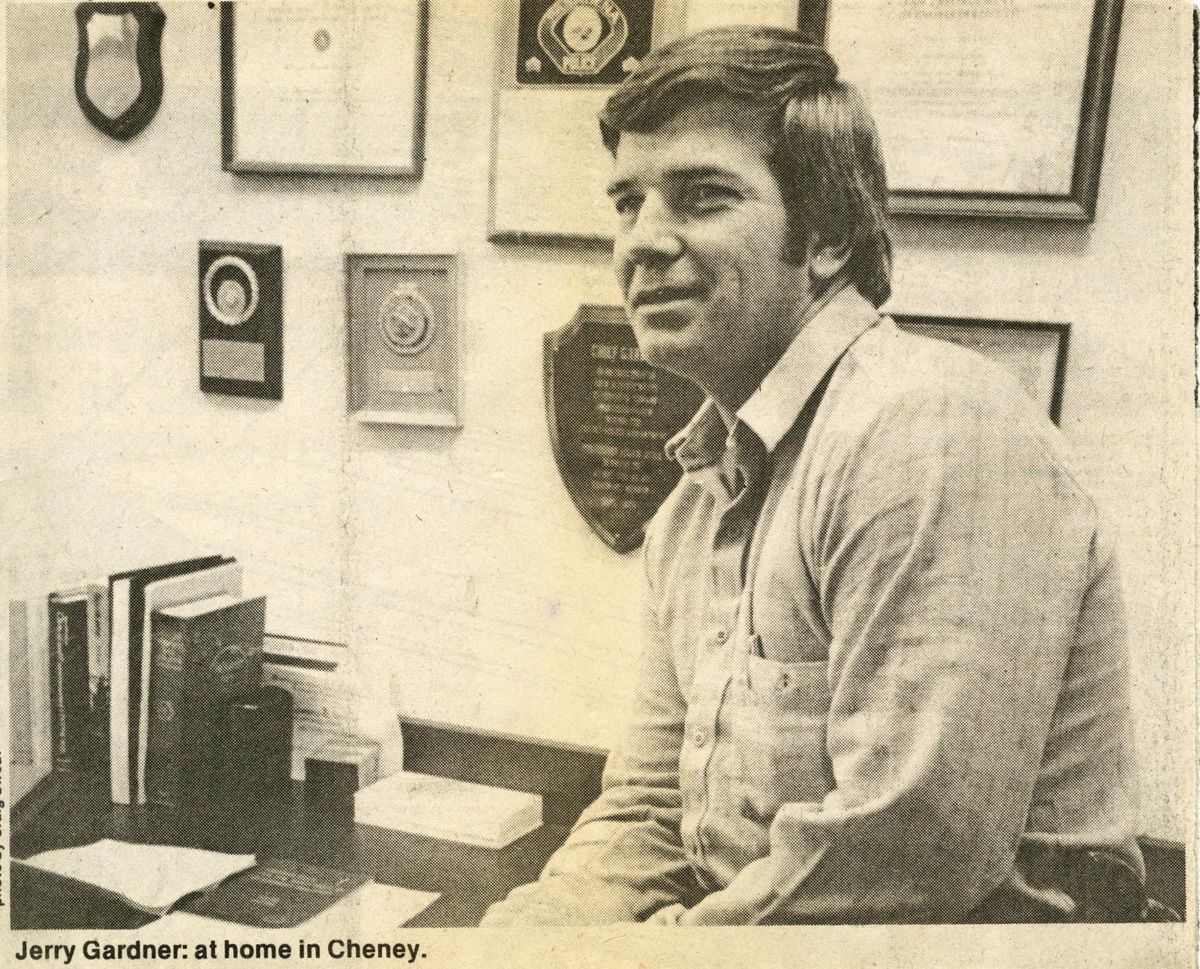

So the small town of Cheney might have seemed an odd fit. Gardner, eager to leave the busy streets of Pasadena, had just turned 33 when he accepted a job as chief of the Cheney Police Department. It was 1974, and the mayor had bet that Gardner, a relatively young outsider, could modernize and lend his wealth of experience to the 11-officer force.

Some who worked with Gardner say the bet paid off. He kept the job for 25 years – appearing on the cover of the National Enquirer and inspiring a novel by an acclaimed mystery writer – and retired in 1999 as the longest-serving chief of any police department in Washington.

Last week, on July 23, Gardner died of complications of a stroke and a medication that breaks up blood clots, according to family members. He was 78.

Tom Trulove, who served as mayor of Cheney during the late 1970s and ’80s, said Gardner was warm and personable, prone to wearing casual shirts and blazers instead of his pressed blue uniform. But, Trulove said, Gardner was also a forceful advocate for his department, willing to butt heads with the City Council on budget matters.

“He came in with a lot of background and experience,” Trulove said. “He’d been with the Pasadena police force, and so he did a lot to begin to build up a real professional police force in the city of Cheney, and we’ve benefited from that ever since.”

Gardner was born in Asheville, North Carolina, but grew up in Los Angeles, playing football and steeping himself in the city’s car culture. He remained a fan of Corvettes through retirement.

After graduating from high school in 1960, he joined the U.S. Army, served in Korea and trained as a military security officer. This, according to family members, was when he developed a passion for law enforcement and strong convictions about right and wrong.

After about a year, Gardner left the Army and began applying to police departments, eventually landing in Pasadena, where he would spend the next 12 years and become a sergeant. He lived in the same apartment complex as Patricia Holder, and the two met one day at the swimming pool.

“He was playing volleyball in the pool with a bunch of people, and I was trying to get my California suntan by laying by the pool. And I got hit in the face with a volleyball,” she recalled recently. “And I looked up, very indignant, and he says, ‘Well, throw the ball back!’ … So then I threw the ball back and thought, ‘What a jerk.’ ”

He introduced himself after the game was over. The two started dating, got married in 1972 and moved to Cheney two years later.

Among other innovations, Gardner is credited with establishing the Cheney Police Department’s first corps of volunteer reserve officers. He also started the D.A.R.E. program in the Cheney School District – where Patricia, who goes by Pat, was a teacher. And in one bout of creativity, he placed a newspaper ad seeking to recruit Eastern Washington University students as confidential “operatives” to assist in drug investigations.

During his first two years as chief, Gardner also devised a novel exchange program that gave his officers a taste of big-city police work. He secured a federal grant, tapped his connections in Pasadena and sent officers to spend a few weeks there, one or two at a time.

Cheney patrol officers rode along with Pasadena counterparts. Cheney detectives learned from Pasadena detectives. The program was dubbed the McCloud Plan, after a ’70s TV show, “McCloud,” in which a deputy marshal from a small New Mexico town is placed on loan to the New York City Police Department.

“We thought it was a great idea, just to get to see what a big department does, and the resources they have versus what we have,” said Jim Reinbold, who worked with Gardner throughout his tenure as chief. “It was quite an education.”

Reinbold was a new officer when Gardner arrived and was later promoted to sergeant. Then he left the police department to take a job as city administrator, becoming Gardner’s boss for the next 17 years.

Reinbold said Gardner made a good first impression.

“He was a young chief and came up from California, you know, which always gives you a little hesitation,” Reinbold said. “But I didn’t have anything to compare him with. And I found him to be very knowledgeable and very willing to teach and share some of his experiences.”

Reinbold recalled that Gardner worked long hours, coming to the station on Sunday afternoons to catch up on weekend incident reports. The chief routinely went on patrol, too, as a way to stay in touch with his officers and the community, Reinbold said.

“He had a good sense of humor, got along with the guys real well,” Reinbold said. “But he would tell you if you stepped out of line a little bit. He’d bring you right back – and do it in a way that you didn’t feel ashamed or hurt or put down. He was very professional.”

A 1979 profile in the Spokane Daily Chronicle said Gardner “deplores the tough cop image and wants the public to see the police for ‘what we are – guardians of the peace, a resource whereby the innocent can be protected, a part of the community that we serve.’ ”

At the time, the Cheney police station had two jail cells. The story noted that Gardner kept them painted in bright colors, which he thought would lift inmates’ spirits.

In 1975, Gardner received a visit from a longtime friend – John Ball, a mystery novelist best known for his 1965 book “In the Heat of the Night,” about a Pasadena detective named Virgil Tibbs who becomes involved in a murder case while visiting his mother in the South. The book was adapted into an Academy Award-winning film starring Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger.

Ball, who lived in Hollywood, had been on many ride-alongs with Pasadena cops and got to know Gardner before he moved to Cheney.

Gardner’s transition to the smaller community inspired Ball’s 1977 book “Police Chief,” about a tired sergeant named Jack Tallon who trades the streets of L.A. for the fictional town of Whitewater, Washington. Unlike Gardner, however, Tallon faces distrust and hostility from his new neighbors and is accused of committing heinous crimes.

Gardner attracted the spotlight again in 1991, when he purchased a police dog named Rex from the Spokane Police Department. Rex, his handlers had discovered, was a pacifist. He wouldn’t bite suspects on command. But Gardner saw potential in the Belgian Malinois, thinking Cheney officers could use him to track people and sniff around for drugs.

The story was humorous enough to make the cover of the National Enquirer tabloid. A photo of Gardner and Rex appeared under the headline “K-9 dog fired – for being too friendly.”

Gardner and his wife retired to Newman Lake, where they raised guide dogs for those with sight impairment. One of their daughters, Darby McLean, described Gardner as “a happy guy” and “an amazing father” who wrote poetry and told elaborate jokes with spot-on impressions.

“He just never soured,” McLean said. “He saw the worst of people, but he would never bring that home or let it affect him.”

Gardner is survived by his wife, daughters McLean and Cara Gardner, four grandchildren, brothers Jim and Jon Gardner, and many extended family members.

A memorial service is scheduled for 2 p.m. on Sept. 15 at the Riverside at Trutina Apartments, 22495 E. Clairmont Lane, in Liberty Lake.

In lieu of flowers, the family asked that donations be made to the local chapter of Guide Dogs for the Blind.