‘We were part of that’: WSU research team made largely forgotten contribution to man’s first moon visit

State Sen. Sam Guess displayed a bit of Coug pride when a reporter asked him on July 20, 1969, what he thought of man’s trip to the moon.

“I was thrilled that our own state educational institution, Washington State University, had some part to play in the success of this most spectacular of all space trips,” Guess told the Spokane Daily Chronicle, in the last of several statements the paper collected that day to commemorate Neil Armstrong’s and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin’s trek across the lunar surface.

As it turns out, the Spokane lawmaker wasn’t just patting himself on the back for a funding decision made in Olympia.

He was giving credit to a team of researchers on the Palouse who directly contributed to what was then a $24 billion effort, spurred by the words of President John F. Kennedy, that sent a manned rocket nearly 290,000 miles to the moon 50 years ago today.

The news of the contribution that came from the Pullman campus a half-century ago came as a surprise to current faculty working at WSU’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, home of the Albrook Laboratory, and others in related fields.

“It’s cool that WSU was involved,” said Guy Worthey, an associate professor in the school’s college of Physics and Astronomy who was unaware of the WSU team’s contribution to the moon mission. “I’m totally convinced they were responsible for delivering water in the large amounts needed for the engines.”

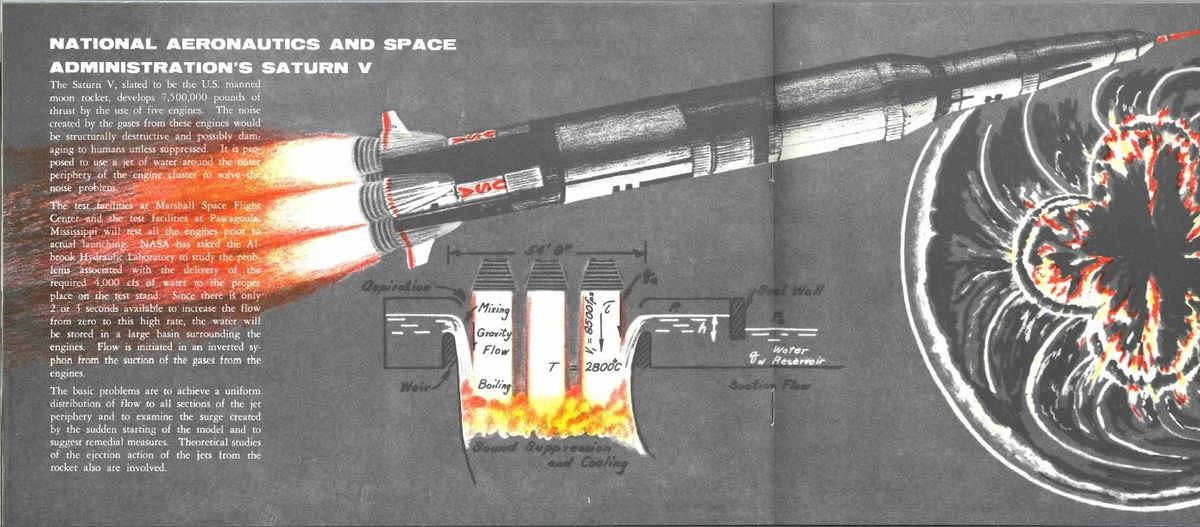

Researchers whose expertise was in water physics and hydraulics earned three contracts from NASA in the 1960s for research on the Saturn V rocket.

“We were quite pleased to be able to do what we did,” said Howard Copp, 85, a former member of the Albrook team who joined the laboratory in 1960 and retired 40 years later from WSU. “It was not a simple matter.”

NASA historical officials, inundated with requests for information on the golden anniversary of man’s trip to the moon, couldn’t confirm this week the extent of the Albrook Laboratory team’s research on the final design of the Saturn V launching tower. But Copp’s memory, as well as records contained in the WSU library’s Manuscripts, Archives & Special Collections department and in The Spokesman-Review’s archives provide clues about the problem the research team was trying to solve.

Above the din

Rockets require enormous amounts of thrust to clear Earth’s atmosphere. For Saturn V, the rocket that carried Armstrong, Aldrin and Michael Collins into space, the thrust necessary was 7.5 million pounds. Five rocket engines were needed to generate that amount of force, firing all at the same time.

The danger posed to the astronauts, and those on the ground below, wasn’t from the heat generated by those engines. It was the noise.

Legendary TV reporter Walter Cronkite was sitting in an observation room 3 miles from the launch of Apollo 4 in November 1967. The sound pressure of the engines at the bottom of the Saturn V rocket caused the room he was in to tremble, and the conspicuously cool Cronkite can be heard excitedly describing the roar on the CBS broadcast that day.

“The building’s shaking here. Our building’s shaking!” Cronkite can be heard exclaiming over the roar. “It’s terrific, the building’s shaking! This big glass window is shaking and we’re holding it with our hands!”

One of Saturn V’s launches generated a roar measured at more than 200 decibels. At that level, physical harm is possible for astronauts, and structural damage can occur to the rocket. A New York Times article on the Apollo 4 launch reported sound levels reaching 120 decibels in the press building, which sat 16,000 feet from the liftoff point. At levels greater than 110 decibels, hearing loss is possible in less than two minutes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rocket’s launch was tested at a NASA base outside Huntsville, Alabama, in the 1960s. News reports of the time included details of downtown windows shattering some 7 miles away.

Enter the team of Albrook researchers, who were tasked with building a scale model of the tower and determining how to move millions of gallons of water quickly enough to muffle the roar down to safe levels during a launch.

To accomplish the task, Albrook researchers drew on previous work, building models of the region’s many hydroelectric dams to determine effects on water tables and aquifers.

E. Roy Tinney, who headed the Albrook laboratory from 1959 until 1968, was the lab’s research director at the time.

“Tinney said the 7,500,000 pound thrust from the Saturn V main stage being developed by Boeing will be so tremendous that it will create a noise equal to the roar of many Niagara Falls,” read a piece published in the WSU Daily Evergreen on Oct. 29, 1965, announcing the second of the three contracts the lab inked with NASA for research. The Spokesman-Review ran one article on the contracts, under the headline “Lab signs new pact in Saturn V studies.”

In the sound suppression system the WSU team envisioned, water is sucked over a weir by the fast-moving gases escaping the bottom of the rocket engines, converting to steam beneath the rocket as temperatures reached 2,800 degrees Celsius (5,072 degrees Fahrenheit), according to NASA calculations. The white vapor that billows beneath the engines is often mistaken for exhaust by onlookers, but it is actually that water instantaneously boiling in the bowels of the launch tower.

After Apollo 4, such systems became standard on NASA launches. Modern systems deaden the roar inside space shuttle cabins to about 142 decibels, according to the space agency’s own publications.

The research performed by Tinney and a team consisting of Copp, John F. Orsborn, Claud C. Lomax, William C. Parrish, W.S. Chie and K.T.H. Liu is contained in a single, red hardbound volume on the lower level of the library at Eastern Washington University. Copp’s name does not appear as an author in the book, but he’s listed as a participant in news accounts and said he worked “on the periphery” with the team responsible for the NASA research.

Obituaries show that Tinney died in 1974, Lomax in 2002 and Orsborn in 2016.

The team’s book had not been checked out of the Cheney library as of a curious reporter’s visit earlier this week.

But Copp called the researchers “a close-knit team” who held some satisfaction that their work helped get man to the moon.

“Anytime we saw or heard about a successful launch, we knew that we were there, we were part of that,” Copp said. “I didn’t make a campaign of it.”

‘Man’s greatest achievement’

Most of those who spoke with the newspaper on that sunny, 90-degree summer Sunday in July 1969 said man’s walk on the moon represented the potential of the human spirit.

“It is a very wonderful thing,” said Ira Woodward, an engineer living in the Comstock neighborhood. “It’s hard to see how young people can keep from aiming for a better education and from resolving to study harder when they witness such an accomplishment and realize that they may someday play a role in an equally historic event.”

That was true for the 4-year-old Worthey, who said watching the landing is his earliest memory.

“I remember later in ’74, they canceled Apollo. I was not a politically aware guy, and that just crushed me,” the professor of physics said.

Viewed in hindsight, the jubilation felt on that day 50 years ago – what one onlooker called “probably man’s greatest achievement” – has felt fleeting for subsequent generations, who never saw another human on the moon after 1972’s Apollo 17 mission.

“Glory of reaching the moon just a phase for Earth,” read the headline in the July 20, 1994, edition of The Spokesman-Review, 25 years after Armstrong’s walk.

But the achievement was a phase that was important in binding Americans together in the midst of the social upheaval of the 1960s, said Cornell Clayton, director of the Thomas S. Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service at WSU.

“It was one of the things that allowed Americans to feel proud about their country,” Clayton said. “In that sense, culturally, it was worth it.”

Millions gathered around their televisions that day to watch otherworldy images broadcast back to Earth.

Marvin Marcelo, a clinical associate professor at the Edward R. Murrow College of Communication at WSU, said technological advances would make a similar cultural event broadcast today much less of a community experience.

“You had a limited amount of information coming out from the three big networks, with CBS being the lead. We were truly tied into that,” Marcelo said. “With social media today, everyone would have a stream going. Now we can individually sit in our bedrooms and watch, but back then everyone was huddled around a TV or radio.”

There were contemporaneous concerns about how much it was costing the American taxpayer. Protesters famously demonstrated at the Kennedy Space Center the night before Apollo 11’s liftoff, arguing the billions spent on the space program should have gone toward feeding and housing the country’s poor.

“I don’t know why our government is spending all that money to go to the moon, because there’s nothing up there worth bringing back,” downtown Spokane dweller and retiree Harold Nelson told the paper. “If there had been men on the moon, they would have been down here a long time ago borrowing from Uncle Sam.”

That feeling may have only been compounded in the years since, as private industry has taken up much of the mantle of shooting large objects into space. Still, there remains a fascination in this region, and among the young, in space exploration, fueled by figures such as Gonzaga Prep alumna Anne McClain and, for some, maybe even the work of civil engineers on the Palouse decades ago, WSU’s Worthey said.

“I think that interest has always been pretty strong. If anything, it’s growing,” he said. “I almost never run into a single individual who says, ‘I have no interest in black holes.’ ”

Fifty years ago today, when Guess, the state senator, was talking to the Chronicle, he rightly predicted that man’s first visit to the moon would forever change mankind’s perspective.

“It was the most expansive thing to happen in my lifetime,” the state senator said.