Front Porch: He was so loyal, relentless, giving

My friend Tony Bamonte is dead, and I am sad – sad for the loss to his wife Suzanne; to the law enforcement community, which he cared about deeply to the eclectic group of people who are interested in the region’s history; and to the myriad people who knew him as their friend.

One of those longtime friends, Bill Morlin, a retired Spokane journalist of note and also a friend of mine, put it this way: “I haven’t seen that many people who are legends, but he’s the kind of guy who in 50 years, his name will still be mentioned.”

What Tony was probably best known for was, in the late 1980s, solving in spectacular fashion what was then the nation’s oldest active murder case, the 1935 killing of a night marshal in Newport, Washington. In doing so, he also exposed police corruption involved with the crime – not the last time he would do something like that.

That experience – which led to the national best-selling book by Tim Egan, “Breaking Blue” – wasn’t all glory and honor for him. Suzanne explained that Tony, who had a 25-year career in law enforcement, “had great compassion for those who the justice system had not served well. And he would not sit still for the blue wall of silence, which, when he took that on, brought him quite some blowback.”

I’ll leave it to others to speak of his public accomplishments, of which there are many. What I’d like to do as I remember my friend is talk about the other stuff, the smaller and, I think, perhaps more telling things about a man who was basically modest and who, his wife said, “had a strong sense that he never quite measured up or did enough.”

Tony, who died of pancreatic cancer July 11, was born May 1, 1942, at Providence Hospital in Wallace. Suzanne told me he loved the fact that screen actress Lana Turner had also been born there.

After serving with the Spokane Police Department (1966-74), including being both a motorcycle officer and a member of the department’s first SWAT team, he became sheriff (1978-91) of Pend Oreille County. Though not an official part of the job, he would go out on his own to do welfare checks. He knew the remote areas where elderly or ill or lonely people lived, Morlin told me, “so Tony would routinely stop by to see how they were. He’d often stay awhile and split wood for them.”

To augment income, Tony started a little sawmill and a lumber company in Metaline Falls and built log homes. He’d peel the logs, notch them, and balance them with chains to put them in place. Both companies were named for Tornado Creek. It was kind of a joke, Suzanne said, because they were located next to this little trickle of an unnamed stream that Tony dubbed Tornado Creek.

One time when Morlin’s sons were about 6 and 8, Bill brought them up through Pend Oreille County and stopped in to see Tony, who was on duty and who asked if the boys would like to try out a jail cell. So he locked them up and dangled the key in front of them.

“He explained that’s what happens to bad people,” Bill said. “It left a forever impression on them, and I’ll tell you, my sons (now in their 40s) have never visited a jail cell since.”

After his law enforcement career ended, Tony and Suzanne focused on preserving the region’s history and in 1996 founded Tornado Creek Publications in Spokane, through which they published books they wrote (as well as work by other authors) that chronicle aspects of Inland Northwest history.

I met Tony when I began writing a feature for this newspaper titled “Landmarks,” in which I’d explore some of the lesser-known historical features of the region, centering each story on some physical place or thing.

Tony would sometimes contact me with ideas, and he, Suzanne and I would sit at their dining room table discussing all sorts of topics to write about. I’d not only leave with one of his research files, but usually the five or six he’d pile on top of that one, files filled with material for other possible stories. He had such boyish enthusiasm for telling stories about this region. And sometimes he and Suzanne and my husband and I would have dinner or lunch together and swap stories.

I asked Suzanne last week which of the many books they wrote or published he thought was most important. She said probably “The Coeur d’Alenes Gold Rush and Its Lasting Legacy,” because of what they considered the gaping hole that existed in telling the origins of the Coeur d’Alene Mining District. “But the motorcycle book is the one he was most proud of,” she said.

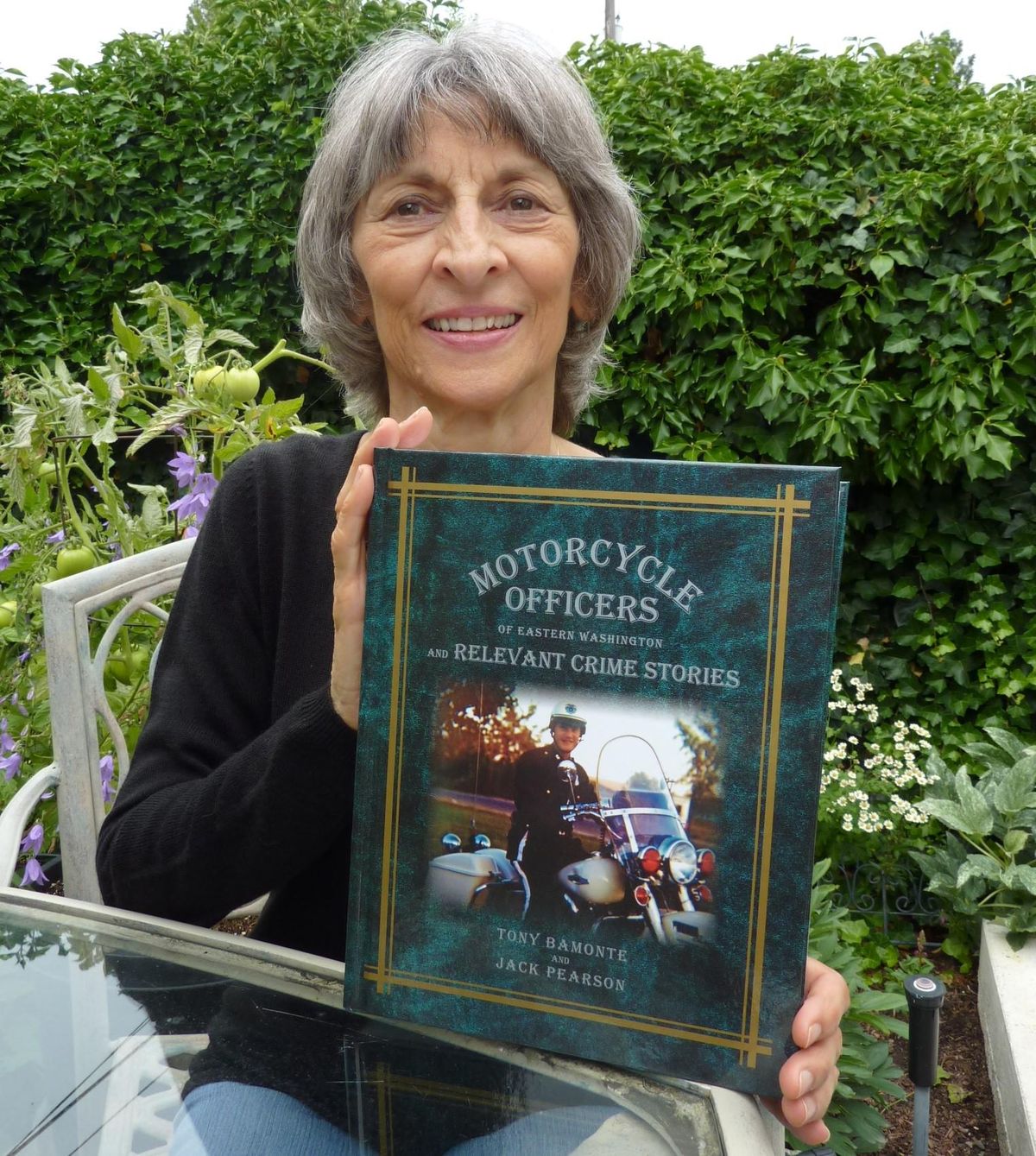

“Motorcycle Officers of Eastern Washington and Relevant Crimes” was published last year, written along with retired Spokane police Officer Jack Pearson – a 656-page tome that weighs 6 pounds and tells with pride the stories of hard-working motorcycle officers and the crimes their careers intersected with, along with the community service these officers did on their own time.

“Tony believed that most officers are good people trying to do the right thing, which is what the motorcycle book highlights,” Suzanne said. “He loved his profession and loved being proud of his fellow officers. In writing the book, he was in touch with a lot of the officers and their families, and he heard from so many of them that they had indeed supported his efforts to expose corruption within police ranks.”

That made him feel good.

And a final personal note. Early last year I was reading Tornado Press’ “WSU Military Veterans – Heroes and Legends” and came across a chapter on Lt. Col. Jack Holsclaw, one of the original Tuskegee Airmen, who grew up in Spokane. I wanted to write about him, but I needed something in Spokane to photograph that tied him to the city. I talked to Tony about that.

The next few days my attention was on something else when Tony called. He had found the house in the West Central Neighborhood where Holsclaw grew up. Tony had some old plat books and followed the clues.

I continued the research and wrote the story. There is a group of organizations in the area that erects plaques and monuments honoring significant people from the area’s history. One of them, the Jonas Babcock Chapter of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, saw the story and followed through. On Monday, they plan to hold a ceremony at the house to dedicate a plaque in memory of Holsclaw.

So here’s how it went. The plaque is being dedicated because there are people who do such things. They learned about Holsclaw through my story. I got to write the story because Tony followed the clues and solved the problem.

That’s what a good police officer does. That’s what a good historian does. That’s what a good friend does.

Farewell, my friend. You are already so sorely missed.