After pharmaceutical companies poured billions of opioid pills into Washington, rural counties try to recover

NEWPORT, Wash. – Pharmaceutical companies flooded Pend Oreille County with more than 6.6 million painkillers from 2006 to 2012, enough for 73 pills per person per year.

That’s according to an analysis of Drug Enforcement Administration data obtained by the Washington Post that shows some rural areas around the country were among the hardest hit from 2006 to 2012, including many counties like Pend Oreille, which sits right in Spokane’s backyard.

In Idaho’s Silver Valley, drug makers supplied more than 6.8 million opioids to Shoshone County, enough for 75 pills per person per year.

And in northwest Montana, Lincoln County pharmacies and drug stores received more than 8 million pills from 2006 to 2012, or about 61 pills per person per year.

One drugstore in Lewis County, Idaho, received an average of 87 pills per person in the seven-year period, the highest rate in the state.

All told, more than 1.8 billion prescription opioid pills flowed into Washington state from 2006 to 2012, with the majority of the supply coming from the top national manufacturer, SpecGx LLC, and distributed by McKesson Corp., the Washington Post revealed.

In Washington state, Pend Oreille County had the second-highest average number of pills per person in a year, the Post analysis found. From 2008-2009 alone, more than 2 million pills were supplied to pharmacies and providers in the county, a Spokesman-Review analysis of the DEA data found.

While the opioid epidemic peaked about a decade ago, the consequences for communities persist.

“That past data demonstrated that we had a problem, and we’re still dealing with the ramifications,” said Matt Schanz, administrator of the Northeast Tri County Health District, which covers Stevens, Pend Oreille and Ferry counties.

Doctors, for their part, were prescribing opioids in line with what the medical field was recommending them for at the time: treating patients’ pain.

Dr. Clayton Kersting, a longtime family practice doctor at the hospital in Newport, the seat of Pend Oreille County, recalls a shift in practice, when he began hearing that pain should be treated as a “fifth vital” for patients. Enter opioids.

“We were duped,” Kersting said, willingly admitting that doctors prescribing opioids to patients were a part of the problem. At the time, it wasn’t widely known how addictive opioids were.

When people started dying of overdoses, the potential problems with opioids surfaced. From 2008 to 2012, prescription opioid overdoses accounted for more than half of all drug overdose deaths in the state, Washington State Department of Health data show, with 499 deaths during that five-year period attributed to prescription opioids.

Opioids are used to treat pain, but they also produce euphoria in the brain, according to the National Institutes of Health, which makes them potentially addictive, even when used for a short time. When a person becomes reliant on a painkiller to feel normal, what started as a prescription can become a substance-use disorder. Addiction is a brain disease, which can literally alter the brain’s wiring, affecting a person’s thought patterns and behavior. Often, people who get addicted to opioids through prescriptions did not intend to.

“A lot of people didn’t want to get addicted,” Kersting said of his patients with opioid-use disorder.

Dr. Charissa Fotinos, the deputy chief medical officer at the Washington State Health Care Authority, was working as a community health care provider in the late 1990s, when leaders at the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries noticed a surge in the deaths of injured, young workers.

“When they dug into that, they noticed it was all people who had been prescribed opioids,” she said.

Eventually, state and federal policies cut back how many pills health care providers could prescribe, but the crisis has led to a persistent and current need for treatment and intervention.

Fast forward nearly a decade, and Washington state is working off a 2018 opioid response plan in order to provide access to treatment and limit prescribing practices statewide.

By November 2017, Washington state Medicaid policy changed to include limits to the amount of opioids prescribers could give to patients, excluding those undergoing cancer treatment, palliative care or opioid therapy. Providers are only allowed to prescribe Medicaid patients under the age of 20 three days’ worth, or 18 tablets of opioids. Patients over the age of 21 are only allowed a week’s supply, or 42 tablets.

When doctors scaled back opioid prescriptions, sometimes without a replacement for pain relief, many patients turned to the heroin or to synthetic opioids, like fentanyl.

While the prescription opioid overdose death rate has steadily fallen in Washington since 2011, the heroin and synthetic opioid overdose death rates have continued to climb. In 2017, heroin and synthetic opioids were responsible for more overdose deaths than prescription opioids in Washington.

“There’s a lot of conjecture about why that is,” Fotinos said. “In the early phase of the opioid epidemic, there were people who started on prescription opiates and transitioned to heroin as their provider stopped prescribing it.”

Whether current heroin overdose rates are associated with opioids is difficult to determine, but years later, treatment is finally catching on statewide. Kersting has used medication-assisted treatment, called MAT, for over a decade, which is an evidence-based substance-use disorder treatment that combines medication management with counseling. MAT is an FDA-approved way to treat opioid-use disorders with medications, like suboxone, which Kersting and his three other MAT-certified colleagues in Newport use.

“If we treat these patients right, we don’t stop their opioids,” he said. “We taper; we wean them off.”

And in reality, Kersting said it is not common in his experience for a person who is addicted to opioids to be completely off of them.

“I get probably 5 to 10% of people off, but most people who you try to ween off will relapse because their brain has been permanently changed, and as soon as you stop them, they don’t like it,” he said.

Physicians must complete an eight-hour training to get a waiver and be MAT-certified to provide the treatment. MAT treatment is available throughout the state, including in some rural counties, due to community-wide support. In Stevens, Pend Oreille and Ferry counties, leaders got local support for a syringe services program that includes a needle exchange and disposal service. A Northeast Tri County Health District coordinator can also make referrals to MAT and other counseling services through the program.

“We’ve really tried to have concerted efforts about how we respond to this situation we find ourselves in,” said Schanz, with the health district.

Schanz noted that one reason Pend Oreille might have had a higher rate of painkillers distributed from 2006 to 2012 is due to its proximity to the Idaho state line. Patients at Newport are not just from Pend Oreille County. In the Tri County Health District area, MAT treatment is available at six sites, which are also the health care hubs of the region: Republic, Kettle Falls, Colville, Chewelah, Wellpinit and Newport.

Medicaid enrollees in Washington state were hit hardest by the opioid epidemic, a Department of Social and Health Services report found. The opioid overdose death rate for Medicaid enrollees was more than four times higher than for those Washingtonians with other insurance from 2006 to 2012. The risk of drug-overdose death is strongly related to behavioral health risk factors.

Newport Hospital and Health Services recognized this early, and hospital leaders worked to get clinical care coordinators into their clinic as early as 2013, so providers could simply do a warm hand-off to counselors under the same roof.

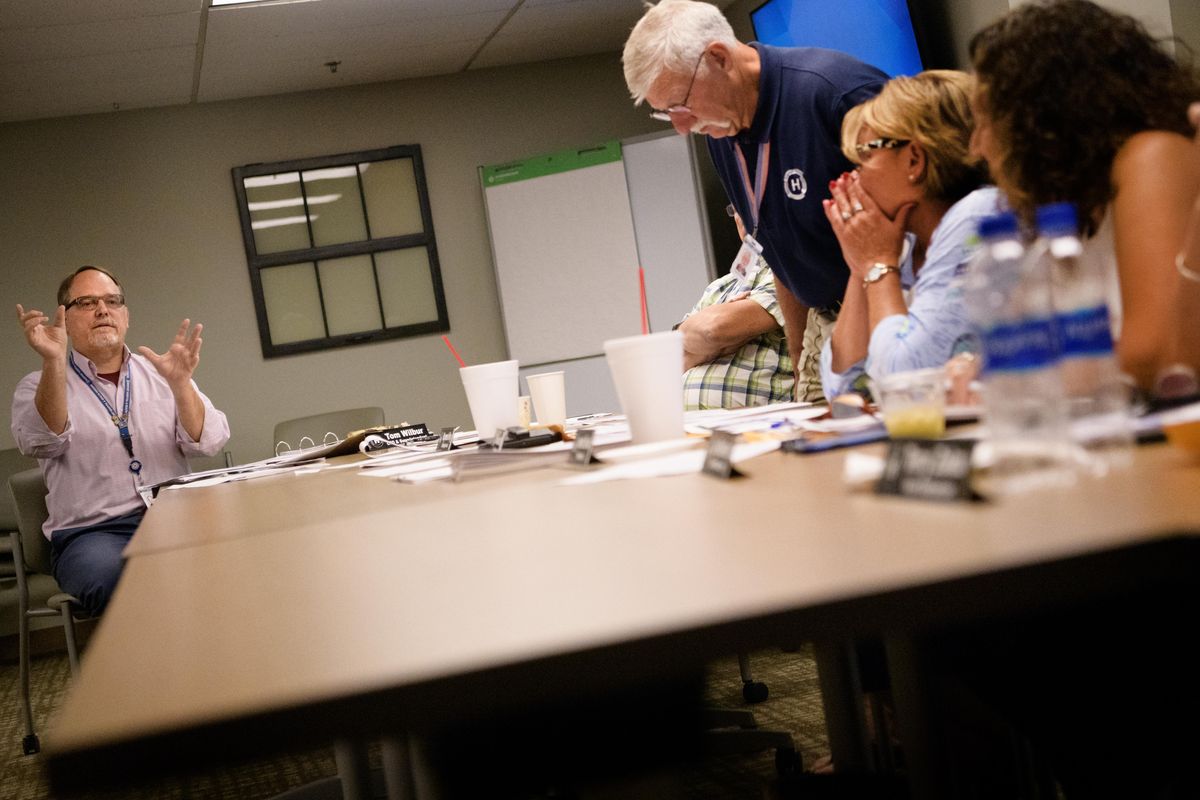

“We started a long time ago trying to coordinate the behavioral health and chemical dependency,” said Tom Wilbur, CEO of Newport Hospital and Health Services. “We’re treating pain and illness which may not be medical.”

Schanz noted that the Northeast Tri County Health District serves a big Medicaid population. The numbers of uninsured people in the northeastern part of the state fell after Washington expanded Medicaid, and MAT is covered by Medicaid in the state. In Newport, 65-70% of patients seen by Newport Hospital and Health providers are covered by Medicare or Medicaid. Pend Oreille County’s current opioid numbers could be higher, too, due to providers’ willingness to continue MAT-treatment for patients regardless of their insurance provider. Kersting said he treats patients in the MAT program who could not find a doctor to do so in Spokane.

“We pick up a lot of patients because we are on the map as MAT providers,” Kersting said. “I have so many patients that are turned away from other providers and told they can’t, so I think our numbers are inflated because we take on people, and we don’t say no to anybody.”

Beyond MAT, however, options for other forms of pain treatment may or may not be reimbursable.

Marian Wilson, a WSU College of Nursing professor and researcher, has studied alternative treatment options, beyond drugs, for pain but notes that the pendulum has potentially swung too far.

“At this point, I think providers are fearful enough for their own possible liability to prescribe opioids the way they did before, and I’m not saying that’s a bad thing,” Wilson said. “The bottom line for me and many people in the pain world is we want every person to be treated as an individual.”

Treatments like acupuncture, massage, physical therapy or even yoga could be used to mitigate patient pain, but whether doctors will prescribe those treatments – and whether insurers will cover the costs of those treatments – is not settled, even more than a decade since the opioid epidemic swept the country.

Wilson and other researchers studied how online pain self-management programs can help manage physical and emotional symptoms for people with pain and opioid-use disorders, but the study also referenced research that shows, “Many MAT participants do not have insurance plans that cover potentially helpful non-opioid pain therapies, such as acupuncture or cognitive behavioral therapy.”

Medicaid now covers cognitive behavioral therapy, which can include mindfulness-based and physical therapy, said Fotinos, with the Health Care Authority. The Legislature has asked the authority to give a report of other evidence-based treatments that the state’s Medicaid program could also cover. That report is due in early 2020. For now, however, people looking for alternative pain treatment outside of MAT are at the mercy of what their insurer will cover.

“As a family doctor, I can write a prescription for anybody I want … but the challenge is if Medicaid doesn’t pay, they have to figure out how to pay for that,” Fotinos said. “Because most folks with Medicaid, if they can’t pay for anything, it becomes this sort of cycle of challenges.”

The opioid crisis might seem like old news, but the state’s response and treatment options for people with opioid-use disorder remains a pressing issue, Wilson said.

“Once we get them into treatment, they find that they can get back into life, they get jobs, go to school, their life can really turn around, so it’s not a bad thing,” Wilson said. “But we need to look at what we’re going to do for these people long term.”

In recent years, more people have accessed MAT treatment throughout the state, but the end-game strategy is far from complete on a state-policy side and many treatment questions remain for those with substance-use disorder going forward, like how to support people in recovery going forward.

“We’re really trying to take a long-term view of this, as opposed to, ‘You’ll be on medicine for a while and then you’ll be good to go,’” Fotinos said. “We know (that’s) not how it works, unfortunately.”

For 24-hour substance-use disorder support, the Washington Recovery Help Line can be reached at 1-866-789-1511.