Nicole Chung finds new territory in adoption stories told through her own eyes as the adoptee

Nicole Chung asked her adoptive mother an important question when she was a child.

“Mama, am I a real Korean?”

Since Chung couldn’t speak Korean, not knowing her native tongue made her question her identity.

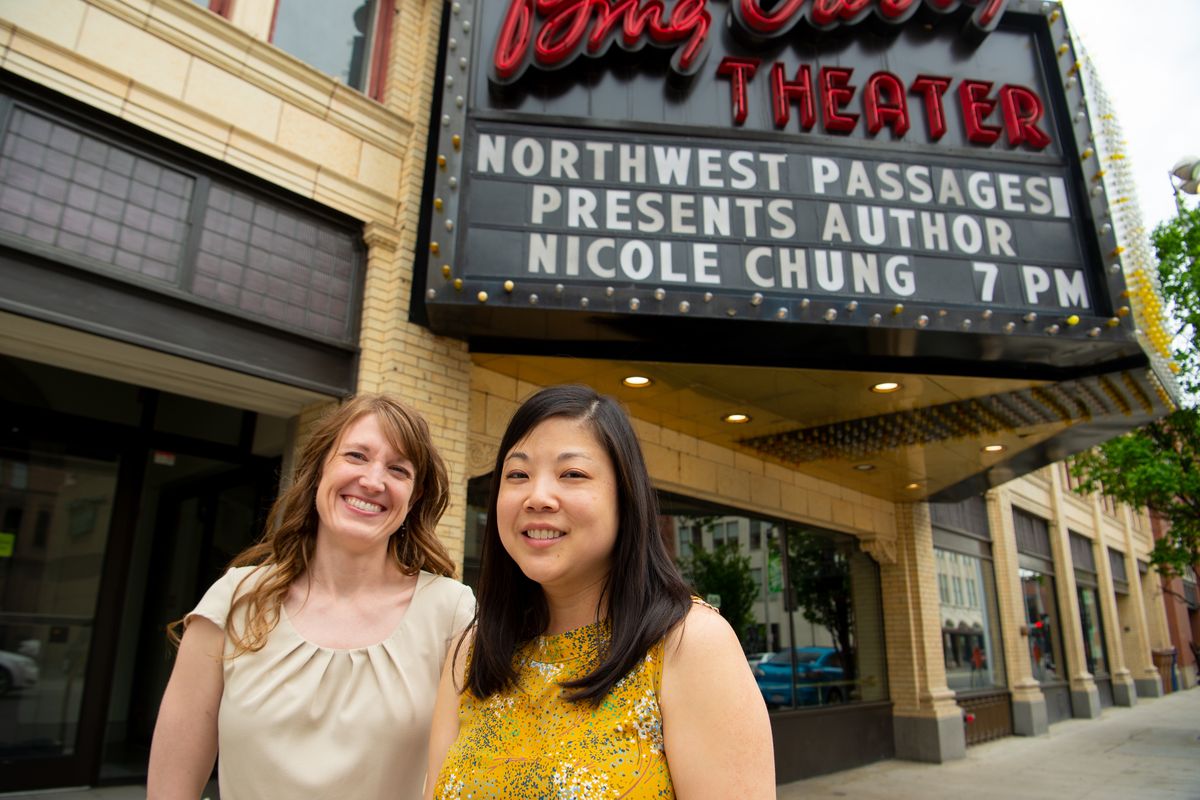

In front of a crowd of Northwest Passages Book Club attendees Tuesday night at the Bing Crosby Theater, Chung discussed her book, “All You Can Ever Know.” The book is a memoir detailing her experiences growing up with adoptive parents in a small, southern Oregon town that was about 1.5% Asian-American.

“All You Can Ever Know,” told from her perspective as a child, filled a gap in the literature of adoption stories, Chung said.

“Most (adoption stories) are from the parents’ perspective,” she said. “Of wanting a child or bringing a child up. I wanted to add an adoptee perspective.”

The book climbed up best-seller lists after publishing in 2018, and Chung said she received a lot of feedback from people in situations similar to hers.

Chung often finds herself in the role of a de facto counselor as people reach out to her for her perspective as an adoptee. Her main piece of advice for adoptive parents: Have more conversations about race and give children the framework to understand the issues they will face before they face them.

“More talking and more honesty, even though it’s really hard,” she said.

As early as second grade, Chung said she remembers facing racism from children. But she didn’t understand what was happening. She didn’t know how to respond. So she found herself “muddling” through those issues alone, she said, because the majority of people she talked to also didn’t understand what she was going through.

“Being an adoptee can be isolating because a majority of people in your life don’t know what it’s like,” she said.

Chung would also hear offhand offensive questions or microaggressions, like people saying she must be grateful to have been adopted. Those comments were weighted with assumptions that her life had to be better now than with her birth family, she said.

Since reconnecting with her birth family, Chung said she learned that they were a family in crisis when they gave her up for adoption as an infant. They had immigrated from Korea a few years earlier, but Chung said the U.S. government could have done more to help them or to find programs for their benefit.

“Clearly one family was carefully served, and one wasn’t; one family was a Korean family and one was a white family,” she said.

Chung said she occasionally meets with her father, who feels remorse over putting her up for adoption. Like her, he is a writer and has been published in Korea.

As a recent endeavor, Chung and her daughters have been learning the language, and one day she hopes to read her father’s work, she said.

“Maybe,” she said, “I will know my father a little bit better.”

The Northwest Passages Book Club event was hosted by The Spokesman-Review.