Wearing a neck gaiter might be worse than no mask at all, researchers find

As the number of coronavirus cases continues to rise nationwide, the recurring message from many public health experts and doctors has been simple: Wearing masks saves lives.

“We are not defenseless against COVID-19,” Robert Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said. “Cloth face coverings are one of the most powerful weapons we have to slow and stop the spread of the virus – particularly when used universally within a community setting.”

But as face coverings have become increasingly commonplace in American life, so have questions about efficacy – and now a group of researchers from Duke University are aiming to provide answers.

In a recently published study, the researchers unveiled a simple method to evaluate the effectiveness of various types of masks, analyzing more than a dozen facial coverings ranging from hospital-grade N95 respirators to bandanas. Of the 14 masks and other coverings tested, the study found that some easily accessible cotton cloth masks are about as effective as standard surgical masks, while popular alternatives such as neck gaiters made of thin, stretchy material might be worse than not wearing a mask at all.

“You can really see the mask is doing something,” said one of the study’s co-authors, Warren S. Warren, a professor of physics, chemistry, radiology and biomedical engineering at Duke. “There’s a lot of controversy and people say, ‘Well, masks don’t do anything.’ Well, the answer is some don’t, but most do.”

The search for a way to determine the effectiveness of different masks began with a request from a professor at Duke’s medical school who was working to provide at-risk and underserved populations in Durham, N.C., with the critical face coverings, according to a news release from the university. Faced with so many varieties of masks all claiming to have virus-blocking capabilities, the professor sought help – in the university’s physics department.

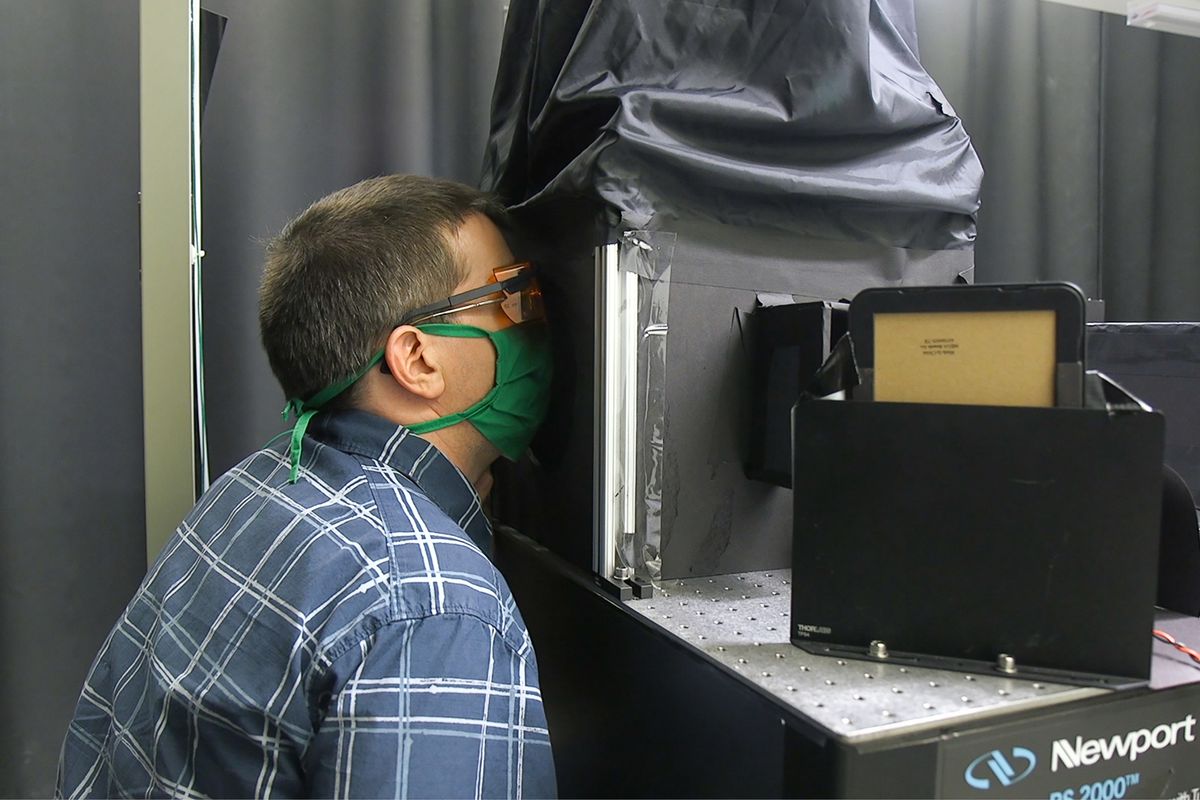

Enter Martin Fischer, a chemist and physicist. Using a simple contraption that harnesses the power of a laser, which can be easily purchased online for less than $200, and a cellphone camera, Fischer created a device that allowed his team to track individual particles released from a person’s mouth when they are speaking. The rest of the setup includes a box that can be made out of cardboard and a lens.

“It’s very straightforward, doesn’t take much resources,” Fischer said in a video produced by Duke. “Any research lab has these things lying around.”

Testing the face coverings was equally uncomplicated, according to the study published Friday in Science Advances, a peer-reviewed journal.

Speakers said the same phrase into the box without a mask and then repeated the process while wearing one. Each face covering was tested 10 times. Inside the device, the airborne particles passed through a sheet of light created by the laser hitting the lens and produced visible flashes that were recorded by the phone’s camera.

“Even very small particles can do this kind of (light) scattering,” Warren said. “We were able to use the scattering, and then tracking individual particles from frame to frame in the movie, to actually count the number of particles that got emitted.”

A fitted N95 mask, which is used most commonly by hospital workers, was the most effective, Warren said, noting the mask allowed “no droplets at all” to escape. Meanwhile, a breathable neck gaiter, liked by runners for its lightweight fabric, ranked worse than the no-mask group. The gaiter tested by the researchers was described in the study as a “neck fleece” made out of a polyester spandex material, Warren said.

“These neck gaiters are extremely common in a lot of places because they’re very convenient to wear,” he said. “But the exact reason why they’re so convenient, which is that they don’t restrict air, is the reason why they’re not doing much of a job helping people.”

The high droplet count could be linked to the neck gaiter’s porous fabric breaking up bigger particles into many little ones that are more likely to hang around in the air longer, Fischer said in the video.

Other types of face coverings that might fall into that category are bandanas and knitted masks, the study found. An N95 mask with an exhalation valve also failed to measure up.