Origins of the Tooth Fairy: One tradition first rose in 17th century France involving a mouse

There is always a little bit of magic when it comes to youths losing teeth. Whether that magic is measured in money or myth heavily depends on the cultures and customs that surround any given child and the loss of their baby teeth. In the United States and other primarily English-speaking countries, the automatic expectation for kids with a freshly fallen baby tooth is a visit from no one other than the Tooth Fairy.

With a first recorded reference dating back to a 1908 Chicago Daily Tribune column advising how “many a refractory child will allow a loose tooth to be removed if he knows about the tooth fairy,” and the according exchanges that follow for lost teeth, the imaginative tale laid the groundwork for the dental-dealing fairy for more than a century to come.

The magic went mainstream in 1927 when Esther Watkin Arnold’s play “The Tooth Fairy” replaced anxiety with excitement for a generation of kids whose lost teeth now became the symbol for an incentivized visit from the mythical creature. After placing it under their pillow and falling asleep, traditional trades were made with small gifts or sums of money for the tooth in question.

Parents have taken the tradition to conveniently encourage healthier teeth habits, issuing more cash or rewards for strong dental hygiene. Today, Delta Dental’s Tooth Fairy Index appraises the cost of a child’s tooth in North America at $4.03, although it varies by region.

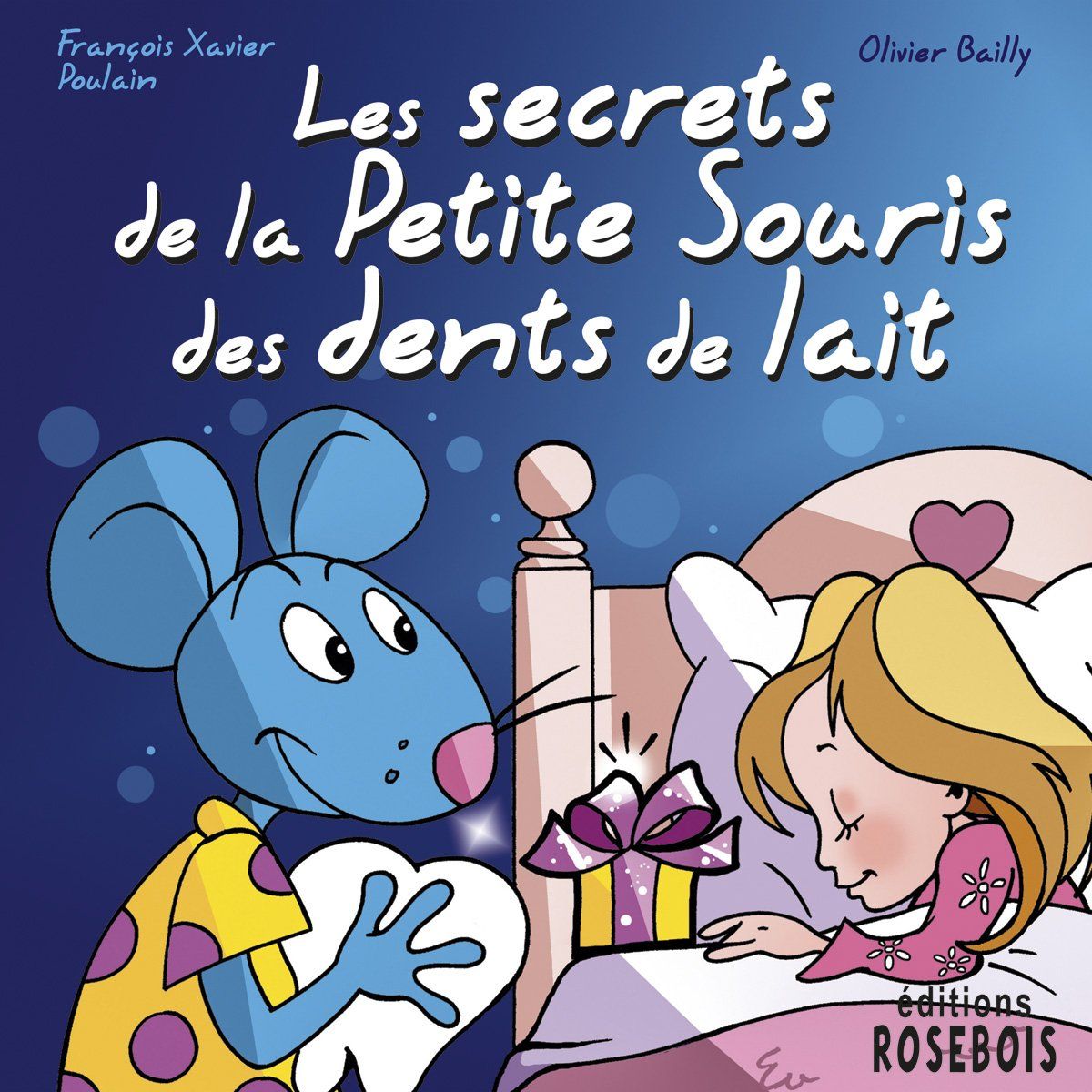

The majority of what makes up modern Tooth Fairy routine can be traced back to 17th century France and a certain fairy-turned-mouse. The tradition first rose to prominence when children’s lost teeth began being placed in their slipper or shoe before going to sleep and waking up with a coin or gift from la petite souris (the little mouse) in its place – a tradition that still stands today.

The origin of the mythical mouse is most likely derived from a story of the same name that details a fairy turning herself into a mouse to defeat an evil queen, introducing the elements of magic that would permeate the tradition down the road.

In largely Hispanic-speaking countries like Spain, Mexico, Peru and Chile, children place their teeth under their pillow for the overnight visiting of El Ratoncito Pérez, or Ratón Pérez, a mouse who takes the tooth and leaves a gift behind in gratitude.

In Argentina, a variation of the tradition has children putting their teeth in a cup of water for El Ratoncito to drink in exchange for gifts. The small-statured and often-parched mouse was inspired by someone of equal form – then 8-year-old Spanish king Alfonso VIII.

After the boy king grew upset because of a lost tooth, Queen Maria Cristina commissioned author Luis Coloma to write a tale to help replace some of that frustration with imagination for the young ruler. The legacy of El Ratoncito endures today in both enduring tradition and a full-fledged museum in Madrid.

Middle Eastern traditions about baby teeth stretch back as far as the 13th century when Islamic writer and scholar Ibn Abi el-Hadid reinforced the idea of tossing lost teeth into the sky and praying in exchange for stronger teeth to take their place. This practice also proved popular in Greece, Turkey and Mexico.

A variation of this tradition is found across Asia, where lost teeth from the upper jaw are thrown on the roof and teeth from the lower jaw are tossed on the ground to encourage the new teeth to grow in the same direction as the old.

Japan, India, China, Korea and Vietnam all exercise this specific tradition. In the Philippines, however, children get to make a wish and then hide their newly lost tooth. If the children can find the original tooth a year after its original hiding, they get to make a second wish.

In Turkey, lost teeth serve as forecasters for children’s future professions. Baby teeth are typically buried nearby a place where the child or their parents envision them working in the future.

While not necessarily a custom that is continued as endearingly today, Scandinavian Vikings often committed a deal of their signature plundering wearing necklaces composed of their children’s lost teeth for protective purposes toward the end of their noted history.

Be sure to check out the Further Review on Page 2 for more about the Tooth Fairy, whose national day is Saturday.