This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

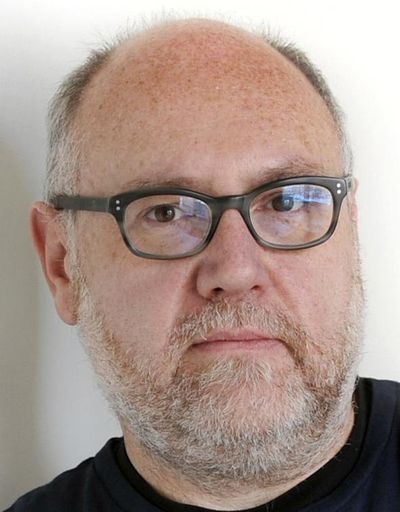

Shawn Vestal: Inequities in how sexual assaults handled on display in Lewiston rape case

Last spring, a 22-year-old Lewiston man took a 14-year-old girl to his house, served her rum while they played video games, lured her into his bedroom and raped her.

Last Thursday, a judge in Nez Perce County, Idaho, told the man – Matthew C. Culletto, described by his attorney as a repentant “nice guy” – he better dang well stay out of trouble from now on or he’ll be “looking at prison.”

To repeat: If Culletto does anything else criminal or violates the terms of his sentence – anything beyond the more-or-less forgivable rape of merely one child – Judge Jay Gaskill will see to it that Culletto might, possibly, perhaps, go to prison.

For now, though, Gaskill gave Culletto 90 days in the Lewiston lockup, and a few stern words in which he chastised Culletto for his “terrible breach of faith” and his hopes that this was just an “isolated, stupid mistake.”

“I hope you understand the consequences of one night’s act,” Gaskill told Culletto at sentencing, according to the Lewiston Tribune.

I imagine Culletto does understand the consequences and is very grateful for them. He committed a crime punishable by a maximum of life in prison, a crime he confessed to, and one for which prosecutors sought five to 25 years in prison. Instead, he was given three months of consequences – with work release! – to weigh in the balance against the lifetime of consequences for the child he raped.

I’m guessing Culletto understands all of that very, very well. I imagine he’s quite thankful to Gaskill for the extraordinary gentleness of the consequences – even with the release conditions that include no drinking for 15 years and a $5,000 fine. I’m sure he’s very grateful for the forgiveness he now understands is built into the system on his behalf.

But does the judge’s justice in this case do anything to render to Culletto an understanding of the consequences to his victim of that “mistake”? Does the punishment fit the crime?

It does not. The offense dwarfs the penalty. Gaskill’s travesty of justice is another instance of the deeply ingrained, sordid tradition of minimizing and mishandling sexual assault in the justice system. At this point, the question might be whether Gaskill understands the consequences for the girl who will live with this for the rest of her life.

There are no crimes for which our justice system fails more consistently and completely than rape and sexual assault. The crimes are vastly underreported, and too often when they are reported, victims run into a police culture of dismissal and minimization and a standard of proof in court that can be hard to clear, even with diligence from investigators.

The Rape and Incest National Network, which calls itself the country’s largest organization working against sexual violence, performed a study in 2014 using statistics and surveys from the Department of Justice. It concluded that for every 1,000 sexual assaults, 230 are reported to police, 46 result in an arrest, five result in a felony conviction and 4.6 result in incarceration.

Meanwhile, in Washington, thousands upon thousands of rape kits remain untested, a crisis that has been treated with the mildest shade of urgency. Last year, the state was awarded a federal grant to make progress on nearly 7,000 untested rape kits – welcome assistance that nevertheless covered less than a fifth of the backlog.

And on top of all that is the granting of sexual-assault mulligans by older male judges to younger male rapists.

Gaskill is far from the first. These cases pop up from time to time, putting a sharp, sour point on the reality of the biases within the system. Surely you remember the case of Brock Turner, the Stanford swimmer who raped an unconscious girl in an alleyway and was served a six-month sentence, sparking national outrage. That judge was justly recalled, and the state of California passed a law requiring tougher minimum rape sentences.

But that case was far from an outlier. Slate writer Lili Loofbourow began compiling a list on Twitter of rape cases in which men served no time at all – a list that is by turns infuriating and disgusting. She wrote a piece last year titled “Why Society Goes Easy on Rapists” that examines the failures across the entire justice system in a thorough, and thoroughly dispiriting, way. (It also questions assumptions about whether long sentences are necessarily the best response to the failures represented by short sentences.)

Gaskill’s judgment demonstrates there remains a substantial reservoir of mercy available to the right kind of rapist – white, young, well-dressed and well-represented, singing the proper song of regret and remorse. And it demonstrates that mercy can consume the entire measure of justice for the victim.

Culletto will be out of jail before spring turns to summer. His victim’s sentence will not end so quickly.