Inland Northwest lawmakers push for House vote on bills to protect Native women

WASHINGTON – Lawmakers from the Inland Northwest are calling on leaders in the House of Representatives to allow votes on two bills to address violence against Native American women and girls, which despite bipartisan support have stalled as COVID-19 has thrown the legislative schedule into disarray.

Central Washington Rep. Dan Newhouse and North Idaho Rep. Russ Fulcher, both Republicans, were among a dozen representatives who signed a July 17 letter asking House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and her GOP counterpart to bring the legislation to the floor before Congress breaks for its August recess.

Both bills passed the Senate in March, just as Congress was turning its attention toward the pandemic, and the lawmakers wrote that the issue can’t wait.

“Each of our congressional districts are impacted by unsolved murder cases or missing person reports from native communities,” the letter, led by Newhouse and Rep. Deb Haaland, D-N.M., reads. “We have heard the outcries from families and loved ones of these indigenous women, and we are working to – finally – begin addressing this issue. In order to do so, we need your support and action.”

The crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women, referred to as MMIW, has been gaining attention after years of activism from Native communities. A 2016 study funded by the National Institute of Justice found that more than 84% of Indigenous women have experienced violence in their lifetimes, and in some counties they are murdered at a rate 10 times the national average, according to a 2008 NIJ-sponsored study.

Ann Ford, a Coeur d’Alene tribal member and youth coordinator for the Spokane Tribe, joined the movement against MMIW after Olivia Lone Bear, a Native woman who had lived on the Spokane Reservation, went missing on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota in 2017. She was found dead nine months later, and the cause of death was ruled undetermined.

“It broke my heart that, even close to home, that girl that I knew was missing,” Ford said. “It seems like no one takes it serious. Is it just because we’re Native American?”

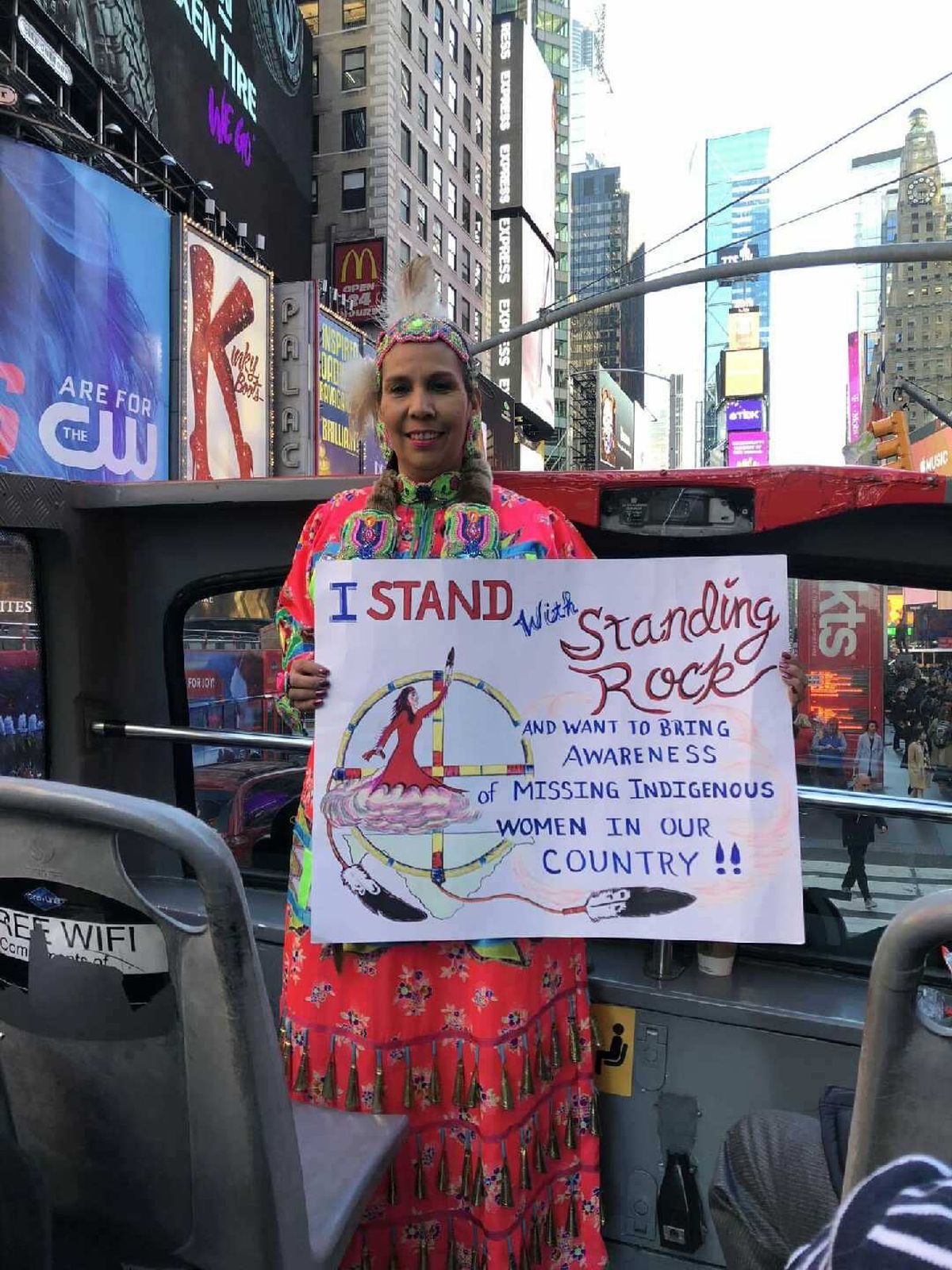

Ford carried a sign calling attention to the crisis to last year’s Indigenous Peoples March in Spokane and as far as Washington, D.C., and New York City.

The problem is neither new nor easy to solve, said Margo Hill, a Spokane tribal member and professor at Eastern Washington University. Hill, a former lawyer for the Spokane Tribe and Coeur d’Alene tribal court judge, said the roots of the problem began when white settlers arrived in North America.

“They didn’t even understand the power of women and how central we were,” Hill said, “and so pretty much upon European contact they thought Indian men were stupid to listen to women and as there was more colonization, European power displaced the roles of women.”

Emily Washines, a historian and member of the Yakama Nation, traces the crisis back to the murder of a Yakama woman in 1855 by gold prospectors. When the woman’s husband killed the miners, Washines said, it set off the three-year Yakama War.

“Why would the United States go to the point of starting a war with us when we were trying to defend our Yakama women and children that were raped and murdered?” Washines said. “This is something that we haven’t really had a conversation about, not within our community as much and definitely not with the FBI or federal agencies.”

The link between resource extraction and violence against women remains, with reports connecting “man camps” – temporary housing often used by the oil and gas industry – to increased rates of sexual violence and sex trafficking, often targeting Native women and girls. Hill also pointed to poverty, drug abuse and the fact that Indigenous children are placed in foster care at a rate 2.7 times higher than the national average as factors making them more susceptible to disappearance and violence.

Another problem, which the legislation in Congress seeks to fix, is the complicated patchwork of law enforcement agencies that are supposed to keep Native American communities safe.

“When you’re looking at violent crimes against Indigenous women, there’s a lot of complicated jurisdictional issues,” Hill explained.

When a crime is committed on a reservation, the agency responsible depends on several factors. Major crimes like rape and murder usually fall to federal agencies, with the FBI responsible for investigating and the regional U.S. Attorney’s Office charged with prosecution. Different jurisdictions apply on “trust” and “fee” land, both of which exist on reservations.

The race of a perpetrator is another complicating factor. In a 1978 decision that dealt with Mark David Oliphant, a white man who assaulted a Suquamish tribal officer on a reservation in Kitsap County, the Supreme Court ruled that tribal courts had no jurisdiction over non-Native people.

Congress partially reversed this policy for domestic violence cases when it reauthorized the Violence Against Women Act in 2013, but tribes still have limited ability to enforce the law.

“We have excellent law enforcement,” Hill said. “We have prosecutors, we have public defenders, but because of the paternalistic, outdated thinking at the time, the Oliphant case decided that we didn’t have criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians.”

These issues hamper data collection and coordination between law enforcement agencies. As of 2016, there were 5,712 cases of missing Indigenous women reported to the National Crime Information Center. At the same time, the U.S. Justice Department’s missing persons database, NamUs, included just 116 cases, according to a report by the Seattle-based Urban Indian Health Institute.

That report identified 506 MMIW cases, which it called “likely an undercount” due to poor data collection. Most Indigenous people in the U.S. don’t live on reservations, and police often fail to identify a missing or murdered woman’s tribal affiliation. The report included a Yakama woman killed in Seattle, which ranked second among U.S. cities with 45 cases.

“About half of our tribal members live off of the reservation,” said Joel Boyd, vice chairman of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. “Many of those are in some of the larger metropolitan areas like Seattle or Spokane. A lot of times we don’t get that statistic back when somebody does go missing.”

The two bills cited in the lawmakers’ letter aim to address these problems. Savanna’s Act, named after a 22-year-old member of the Spirit Lake Nation murdered in 2017, would direct the Justice Department to develop new law enforcement guidelines, require better training and data collection, and improve tribes’ access to federal criminal data.

The second bill, the Not Invisible Act, would create an advisory commission to recommend changes to the Justice and Interior Departments, aiming to improve coordination between federal agencies, tribal and local police, and victim service organizations.

The two bills are part of a broader legislative effort to address the longstanding problem. Another bill Newhouse supports, the BADGES for Native Communities Act, aims to address data-sharing barriers and aide staffing shortages at tribal police departments. Other priorities include bills to reauthorize the Tribal Law and Order Act and Violence Against Women Act, both of which include provisions meant to address the MMIW crisis but appear unlikely to pass in the current session of Congress.

In November 2019, President Trump also signed an executive order establishing a task force, dubbed Operation Lady Justice, to improve federal agencies’ response to the MMIW crisis. Listening sessions with tribal leaders, originally scheduled to begin in March, will take place virtually starting in August due to the pandemic.

Boyd said Savanna’s Act, the Not Invisible Act and the BADGES Act would all bring welcome changes, but he also called for greater jurisdiction for tribes over non-Natives. The Colville Reservation lies in both Okanogan and Ferry counties, and he said while the tribes have good relationships with both counties’ sheriff’s departments, there’s room for improvement.

“Being able to enforce crimes like that against our own women and children would go a long way in stopping some of this from actually occurring,” he said. “When they’re hitting our communities, we take that very seriously, but sometimes with the overlapping jurisdiction you don’t see as much interest (from other law enforcement agencies) because they cover a bigger area.”

Bernie LaSarte, a Coeur d’Alene tribal member who works to prevent sexual and domestic violence as founder of the tribe’s STOP Violence Program, agreed that better coordination is needed.

“We’ve got a problem that’s beyond us,” LaSarte said. “It goes beyond our boundaries and I think it’s going to take certainly more than tribes to deal with it, because it does affect everybody.”

Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., was an original cosponsor of Savanna’s Act in the Senate. Her fellow Washington Democrat, Sen. Patty Murray, and Idaho Republican Sens. Mike Crapo and Jim Risch all later joined as cosponsors. Newhouse introduced the House bill, which both Fulcher and East Idaho GOP Rep. Mike Simpson joined along with several Western Washington lawmakers.

Savanna’s Act and the Not Invisible Act both passed out of the House Judiciary Committee in March, clearing the way for a vote in the full House, but Congress has a tight schedule with just two weeks before the likely start of an annual break in August.

Washines said she is heartened to see lawmakers like Newhouse, who represents the Yakama Nation, pushing the bills, but she isn’t surprised when Congress doesn’t make them a priority.

“On the one hand, I remain optimistic,” she said. “On the other hand, when I don’t see action, I’m like, ‘Well, our first report to the U.S. government for MMIW resulted in a war.’ They were willing to go to war with us to extract gold more than protect our Yakama women, so this is just a pattern that has continued.”