A U.S. Army Air Force B-25 bomber, attempting to maneuver over New York City in a heavy fog, flew into the side of the Empire State Building on this date 75 years ago. All three aboard the plane and 11 in the building itself were killed.

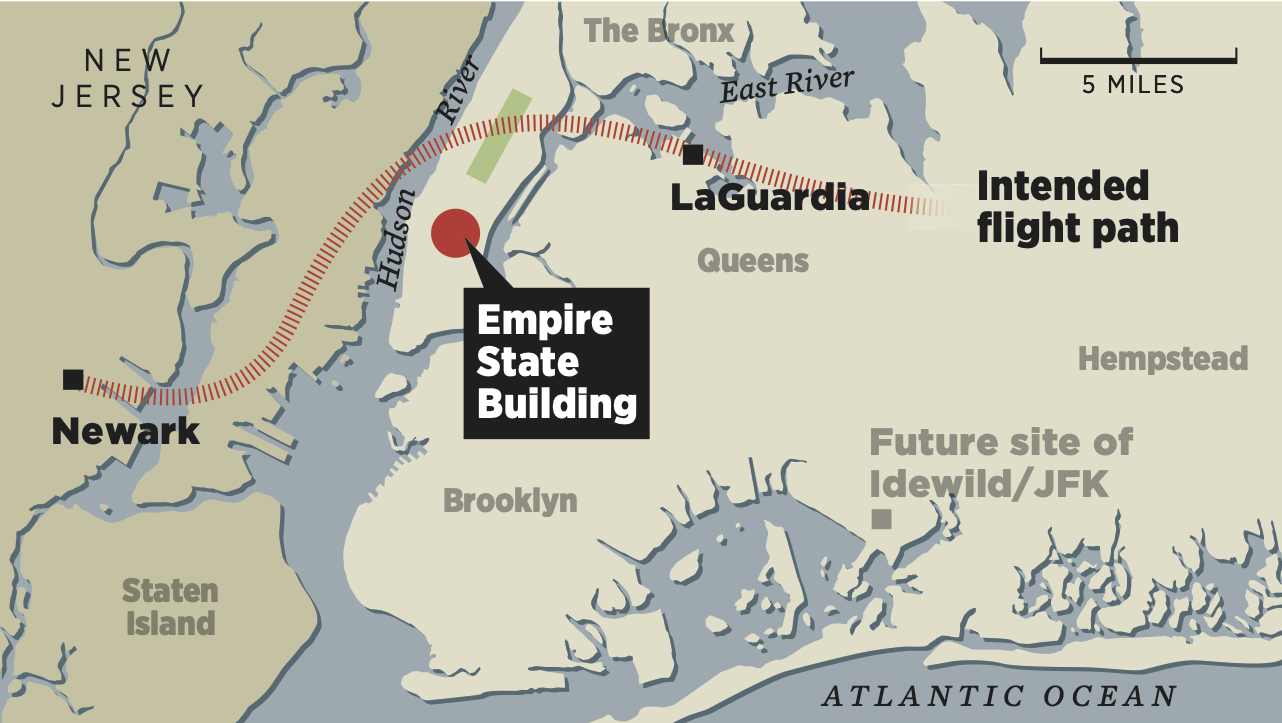

Lt. Col. William Smith was a highly decorated pilot with 34 combat missions over Europe. Freshly back to the States, Smith was to be transferred to duty in the Pacific. But first, he had been sent from Bedford Field near Boston in a B-25 Mitchell bomber to confer with his commanding officer in Newark, New Jersey.

Smith found the New York metro area covered with heavy fog, so he flew toward LaGuardia Airport in Queens and requested a landing clearance. He was told to proceed to Newark, as long as he had three miles of visibility.

So he did. But whatever visibility Smith had didn’t last long. As he flew over Manhattan, Smith’s last words to LaGuardia tower were: “From where I’m sitting, I can’t see the top of the Empire State Building.”

Smith’s 12-ton B-25 plowed into the 79th floor of the Empire State Building at about 200 mph. The plane’s wings were sheared off, parts of them clinging to the gaping hole in the side of the building. Eight hundred gallons of aviation fuel poured out of the punctured tanks and down hallways and stairwells. Flames shot upward as far as the 86th floor observation deck.

♦ ♦ ♦

Smith’s mishap took place just before 10 a.m. on July 28, 1945 – which, thankfully, happened to be a Saturday. There were only a handful of sightseers on the observation deck that morning. Much of the rest of the building was taking the day off.

However, there was one organization on the 79th floor hard at work that Saturday: The National Catholic Welfare Council. Nine women were instantly burned to death by flaming aviation fuel. One of the volunteers who survived, Catherine O’Connor, said:

“There were five or six seconds – I was tottering on my feet, trying to keep my balance – and three quarters of the office was instantaneously consumed in this sheet of flame.

“One man was standing inside the flame. I could see him. It was a co-worker, Joe Fountain. His whole body was on fire. I kept calling to him, ‘Come on, Joe; come on, Joe.’ He walked out of it.”

Fountain would die of his injuries four days later. One other man – the publicity officer for the Catholic charity – was killed when the force of the blast threw him out of a window.

♦ ♦ ♦

Both of the plane’s engines tore off the wings and shot through the building. One fell into an elevator shaft. The other hurtled completely through the building, ripped out the other side and then fell 900 feet through the roof of a nearby building, destroying a penthouse art studio (below).

Twenty-year-old Betty Lou Oliver was working her very last day as an elevator operator and was on the 80th floor when the plane hit the building. “The elevator seemed to stop and shudder for a moment,” Oliver said. “Then it began plummeting downward.”

Oliver’s elevator fell more than 1,000 feet into the building’s sub-basement, where the concrete floor “was crushed like an egg shell,” said an official for the Otis Elevator Company. Rescuers cut her out of the wreckage to find her burned, bruised and her back broken.

Oliver would make a full recovery and would have three children. She would die in 1999 in Fort Smith, Arkansas, at age 74.

♦ ♦ ♦

Firemen and medical workers responded within minutes. With several elevators out, they could ride only as far as the 60th floor, and then walked the rest of the way up.

Col. Smith was killed, along with his co-pilot and a third man who had been along for the ride that day. The death toll for the crash: 14. The crash caused about $1 million in damage — that would be more than $14 million in 2020 dollars.