Book review: The past lives and present glories of the Louvre

The Louvre is shuttered now, empty of humankind for the first time in eight centuries. But in a normal year, 10 million people cross the threshold of the world’s largest museum, one of the biggest structures on the planet. Theirs can be a bewildering, even forbidding, experience. The Louvre’s 36,000 holdings, only a 10th of which are on display, are chronologically diffuse and promiscuously inclusive.

The building’s eccentric footprint and daunting size – its longest gallery is nearly a half-mile long – might be why most visitors settle for paying their respects at the five stations of the cross: the Mona Lisa, the Venus de Milo, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, “Liberty Leading the People” and the gift shop.

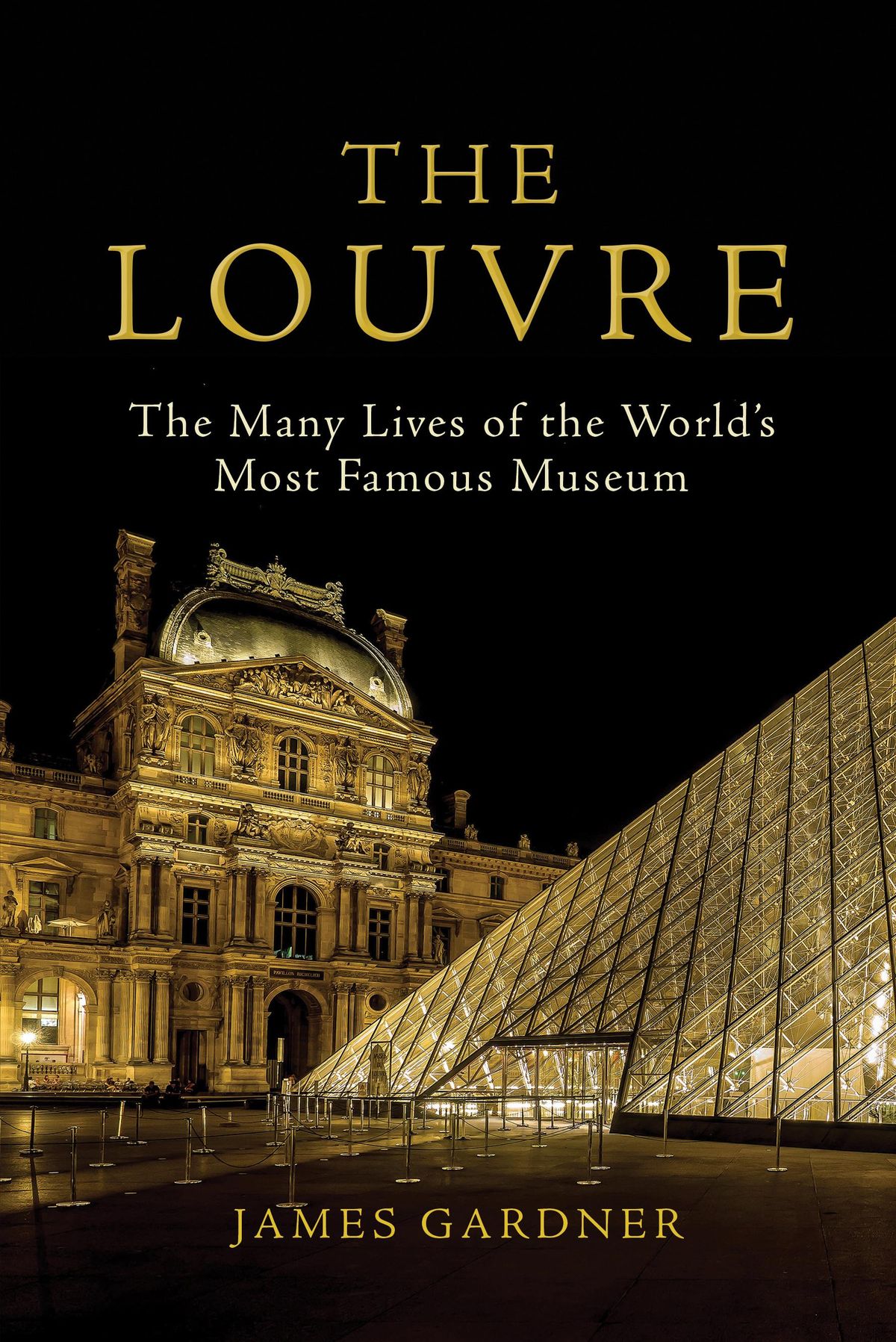

In his courageous and erudite new book, “The Louvre: The Many Lives of the World’s Most Famous Museum,” critic James Gardner is bold to take in, and take on, what few mortals have the chance or the stamina to do. Think of reading this book as the full experience you are temporarily denied today or may never have had the energy to undertake.

Alone among the greatest museums of the contemporary age, the Louvre was not built as a museum. The foundations (unearthed only recently) date to the 12th century fortress of that name, and upon them were erected over centuries a sprawling palace that became, off and on, the seat of the French monarchy.

In whatever incarnation, the Louvre has always been intimately tied to the glorification of the French king and, before and after royalty’s final demise in 1871, to the transcendent eminence of France. Yet as a residence, it had to share the monarch’s affections with other, more sumptuous dwellings (Amboise, Blois, Fontainebleau).

Louis XIV spent the first decades of his long reign enhancing and investing in the Louvre, then abandoned it entirely for the magnificent palace he built at Versailles, where he moved the court. The Louvre stood idle and decaying for more than a century afterward. The Louvre grew up and out (westward) not abstractly, but toward another magnificent pile, the Palais des Tuileries.

The museum’s 1610 Grande Galerie – in Gardner’s words, “pharaonic in ambition and almost superhuman in scale” – was conceived as a grand passageway to the Tuileries, Paris home to the kings and the Napoleons. In 1871, at the bloody end of Napoleon III’s rule, the angry citizens of the capital burned the Tuileries to the ground, making it a “phantom limb” today remembered by the eponymous gardens that stretch to the Place de la Concorde.

That bitter denouement of the Second Empire does not diminish the Bonapartes’ contributions to the Louvre. Napoleon I was a prodigious looter of art and antiquities from every realm he conquered, of course, but the credit for the great museum as we know it goes especially to his nephew Napoleon III, in power from 1848 to 1870.

His passionate reinvigoration of the Louvre as a public showcase for Western civilization’s greatest art is singular in a reign better remembered for the wholesale modernization of the Paris cityscape, which the emperor delegated to Baron Georges-Eughne Haussmann. The contemporary visitor to the Louvre enters via the Carrousel, through the late 20th century glass pyramid of architect I.M. Pei.

That once-shocking addition and the radical reorientation of the whole museum created a new public nexus in a zone originally the Louvre’s unlovely backside. One casualty, for Gardner – who admires Pei – is the facade few visitors today might see: the one that faces east. Often called the Colonnade, and in contrast to the “drab adequacy” of the facade facing the pyramid, this eastern front is “as fine a piece of architecture, classical or otherwise, as will be found anywhere in the world.”

Here and throughout, Gardner is intent on persuading us to see the Louvre for itself, to appreciate the container as much as the content. Most visitors to the Louvre today do not come to admire its interiors but what those interiors contain. They are so eager to get to the paintings on the second floor they most often ignore the stairways that enable their ascent.

They are so dazzled by the masterpieces on the walls they miss the ceilings of those chambers, ceilings which, to the “period eye” of the Second Empire, were among the crowning glories of the age. Every molecule of the Louvre’s Second Empire interiors feels charged with meaning and formal consequence, and each room is a product of hundreds of discrete acts of aesthetic judgment.

As for the museum’s best-known artifact, the tiny Mona Lisa (La Joconde), Gardner recalls that Leonardo da Vinci’s early 16th century portrait became the icon it is today only in the late 19th century and ponders the peculiarity of its celebrity. He laments the difficulty of appreciating the painting from a crowded distance and behind tinted bulletproof glass, but “The main impediment to appreciating Mona Lisa, oddly, is our constant exposure to it. … Like a dollar bill or an American flag, it is so familiar that we no longer see it.”

Gardner is keen to explore the “many lives” of his subtitle and to point out all the ways the Louvre even today remains a work in progress and polyfunctional. It had military uses from the outset and episodically into recent times. It once housed (and the king underwrote) many of the artists and artisans whose work would adorn the palace and museum. The French Ministry of Finance occupied what is now the Richelieu wing along rue de Rivoli until 1993.

President Frangois Mitterrand, who served from 1981 to 1995, masterminded the remake of the complex, which created underground one of the biggest retail malls, biggest convention centers and biggest parking garages in Paris. Gardner, bless his heart, does not overlook even the most prosaic of these. The twilit acres of subterranean parking are “a stunning achievement, if not a thing of beauty,” he observes and “can even be read as a sly parody of the glittering, sunlit splendor of the upper regions.”

Open the book and enjoy the visit.

Trueheart is a former Washington Post foreign correspondent and former director of the American Library in Paris.