New guidebook delivers maps, directions and insight on routes from Spokane to Cd’A

Public trails boost the local economy. That alone might be reason to build and promote trails even if they weren’t so wildly useful, healthful and environmentally wise.

When listing a house nowadays, real estate agents jump at the chance to note if it has easy access to, say, the Centennial Trail, which stretches along the Spokane River 63 miles from Lake Coeur d’Alene in Idaho to Washington’s Riverside State Park.

Routes for hiking, biking and other modes of recreational travel are also selling points for recruiting businesses and industries.

The Spokane-Coeur d’Alene area is rich with national forests, refuges and even wilderness areas just a few hours away. The region’s reputation for trail recreation also is bolstered by sprawling networks at Mount Spokane and Farragut state parks.

But just as important are trails in and close to town. These are the routes ripe for a quick morning nature break, a traffic-free commute to work, a regular lunch hour exercise circuit, or an afternoon break for a parent with a kid in a jogging stroller.

The benefits of close-to-home or near-work trails may not be specifically on our minds when we set out on the High Drive bluff trails on the South Side of Spokane, the Ben Burr Trail to the city core, or along the Little Spokane River on the North Side. Most of us “hit the trail” simply to clear our heads, refresh our lungs, rev our heartbeat and leave our troubles behind.

Trails are a refuge for appreciating blooming wildflowers, fall colors, soaring hawks and the occasional moose. Drumheller Springs City Park has only a modest mile of trail, but it loops through 12 acres that still explodes with colorful camas, biscuitroot, bitterroot and other wild plants. The springs and wild edibles created an oasis that attracted Native Americans for hundreds of years. The park was named after Daniel Drumheller, who tapped the springs around 1880 for a pig farm.

Nevertheless, Spokane’s forefathers paved the way for trail consciousness. In 1898, cyclists persuaded the city council to authorize a tax for building bicycle paths. In the following decade, city businessmen realized that creating appealing neighborhoods and parks in the growing frontier town would enhance their quality of life, not to mention the value of their real estate fortunes.

Parks became integral to the area’s culture. While I was researching my latest trail guidebook, Todd Dunfield of the Inland Northwest Land Conservancy offered some impressive data about our quality of life as we walked the proposed Rimrock to Riverside route that eventually could link Palisades Park to Riverside State Park. “Most parks have some sort of trails,” he said, “and 83% of Spokane residents live within a half mile of a park.”

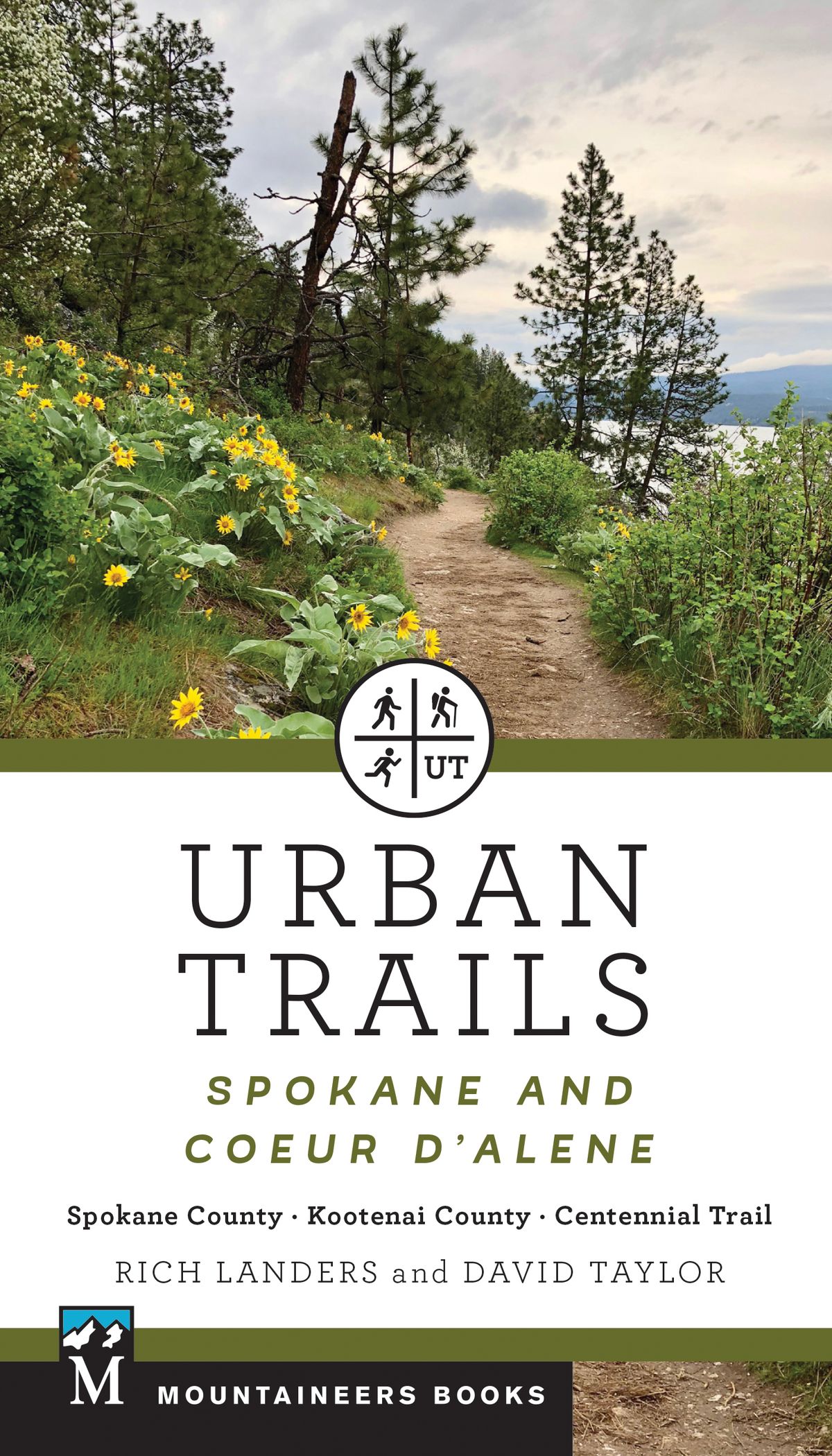

The just-published book, “Urban Trails: Spokane-Coeur d’Alene,” which I co-authored with Kootenai County hiker David Taylor, features more than 60 areas with notable trails convenient to residents of the two cities. Some headliners like Tubbs Hill attract visitors from far and wide; other parks and trails mostly serve their neighborhoods.

Sixteen of the trail systems detailed in the book are ADA accessible and 16 are served by public transit.

Others are remote, in a close-to-home sort of way.

The book includes maps and directions for treks, short and long. While mobile apps might tell you where you ARE on a trail, “Urban Trails” goes the extra mile to offer nuggets of information about trail history and land ownership as well as hints at whom to thank for trail maintenance, and how to get involved.

The appendices are packed with contacts for land managers, trail and conservation organizations, plus an excellent index and a brief guide to the area’s signature wildflowers. I snapped the 24 wildflower photos (and many more) while hiking the trails featured in the book.

Taylor and I also photographed a wide range of wildlife while exploring these trails, including osprey, bald eagles, deer, wild turkeys, waterfowl, reptiles, marmots and moose. We also detected enough bear and cougar tracks to justify our decision to carry bear spray on some hikes.

Many public agencies are answering the demand for trails by integrating them into infrastructure projects. High-profile examples include the Children of the Sun Trail linked to the north-south freeway project. It’s being engineered complete with dedicated bridges and underpasses. More than 7 miles is done in what will be a 14-mile route from the Wandermere area linking with the Centennial Trail near Greene Street Bridge.

Trail partnerships are being seen as win-win deals. For example, the Village at Riverstone in Coeur d’Alene promoted its “live, work, play” marketing concept by donating to building the city’s Prairie Trail. The route follows an abandoned railway from Riverstone Park businesses to residential areas and linking to the North Idaho Centennial Trail.

The Spokane County Conservation Futures Program, funded by a voter-approved property tax levy, has leveraged state, federal and private funding to preserve – so far – about 50 public conservation areas totaling about 9,000 acres of incredible beauty and value. They are revered by locals who crave muscle-powered escapes where deer roam, owls hoot and coyotes howl.

“Urban Trails” celebrates the volunteers who have jumped in to make a good thing better by building, maintaining, connecting and signing trails through these conservation areas.

Paul Knowles, Spokane County Parks planner who’s directing a boom in trail development, says at least 13 miles of new single-track trail have been built by volunteers since 2016 on county parkland. Even more impressive is how a combination of land acquisition, trailhead parking development, volunteer trail construction and signage have linked double- and single-track into impressive “trail systems.”

For example, Mica Peak Conservation Area has a 14.8-mile trail system, Antoine Peak has 10.8 miles, Glenrose has 5.6 miles, Iller Creek as 7 miles and McKenzie has 6 miles. The list goes on.

The Spokane Mountaineers, Washington Trails Association and Dishman Hills Conservancy have organized thousands of hours of volunteer trail work to clear way for the parade of hikers and bikers that follows.

Some of these volunteers, including Lynn Smith of the Mountaineers, have developed pro-level skills needed for designing sustainable trails and special projects, such as building the new footbridge over the creek in The Cedars Conservation Area at Liberty Lake Regional Park.

Evergreen East mountain bikers also have dug into the local effort by designing and building enlightened routes for walkers and cyclists in the 7.3-mile trail system at Saltese Uplands.

Of course, the opportunity to develop and use trails wouldn’t be possible without the advocates who secured the open spaces in the first place. Too many to name, “Urban Trails” simply offers them all a tip of the hat by dedicating the book to the memory of Diana Roberts, founder of Spokane’s Friends of the (High Drive) Bluff, and Scott Reed, Coeur d’Alene’s watchdog for Tubbs Hill and other public places.

The guidebook is small enough to pack along for a hike so you can follow the maps and be informed about the surroundings. For example:

- The footbridge across the Spokane River at Bowl and Pitcher is the only suspension bridge in Washington State Parks. The 216-foot span was built in 1940-41, refurbished in the 1950s and renovated in 1997. The stairs on the south side were built in 2012.

- From the trail along Medical Lake, one can see that the rock formations on the east side of the lake are basalt while the rocks on the west side are granite. The book explains how this occurred.

- The 518-acre Post Falls Community Forest is a haven for hiking trails along the Spokane River thanks to environmental rules that required the city to create a reuse area for reclaimed water.

- Mirabeau Point Park is on the site of the former Walk in the Wild Zoo. The seasonal waterfall pours over a rock cliff where Bengal tigers once lounged.

- Indian Canyon Park, dominated by ponderosa pines (Spokane’s official tree) holds the largest documented Douglas firs in Spokane County.

- The Haynes Conservation Area came within a few signatures of being a 103-house development along Little Spokane River instead of a 97-acre forested park with river access and 3 miles of trails.

The effort to secure more open spaces is as urgent as ever to offset the onslaught of development zeroing in on this region. The COVID-19 era has given us a look at the future as people looking for an escape have flocked to parks and conservation areas in unprecedented numbers this year.

“Urban Trails” notes that as it went to press efforts were being made to secure the excellent wildlife habitat and nearly 4 miles of walking routes along the Little Spokane River at Waikiki Springs.

Just last month, the Inland Northwest Land Trust announced it had purchased 95 acres of the area for preservation.

That’s the kind of progress we need to balance our region’s five-star quality of life rating with the other kind of progress.