Ocean to Idaho: End of a migration leaves reporter battered, bruised like the salmon

IDAHO FALLS – At the end of the 850-mile journey that chinook salmon make from the ocean to the central Idaho wilderness, the fish are beat up, decaying and will soon die.

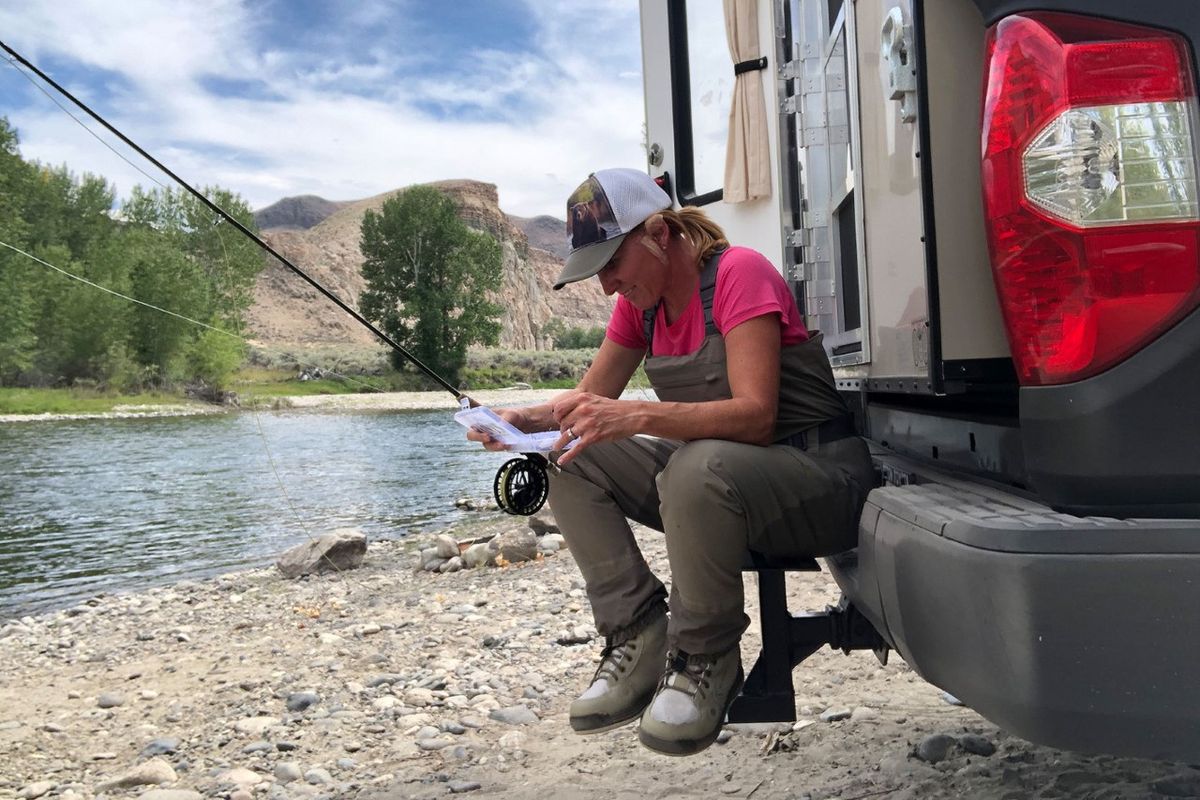

Outdoor journalist Kris Millgate, who followed the fish’s progress all summer on her “Ocean to Idaho” project, logging more than 4,600 miles, also felt especially beat up at the end of her journey.

“I have bruises, a broken camera. I have stitches in several places right now, and I got diagnosed with skin cancer,” Millgate said. “It seems like I’m falling apart just like the fish were toward the end. That was really uncomfortable. There was no way I wasn’t going to finish. The fish were going to finish, so was I.”

Millgate started her project in the spring at the mouth of the Columbia River as the salmon began their migration back to Idaho. She compiled weekly reports and interviews on the fish’s obstacles, and chats with stakeholders such as Native Americans, biologists and dam operators, at various steps in the fish’s journey back. The weekly updates are posted online for people to follow the story.

Last week, she posted her final report after the fish arrived at spawning grounds in the Yankee Fork of the Salmon River in central Idaho.

“I wrapped up on the Yankee Fork watching salmon spawn and die,” she said. “It was literally the end.”

She was able to keep tabs on where the Yankee Fork migrators were at as their PIT tags (a computer-based monitoring system) were read as they passed through dams on the way home.

Millgate said she almost missed the final act of the saga. This year only 29 chinook salmon returned to the Yankee Fork. When she finally found a pair of salmon spawning, she was awestruck.

“I’m not kidding, I freaked out. I was so thrilled,” she said. “Sometimes when you’re on stories, there is that moment where you slip out of work mode. Out of respect for such a rare, wild sight. It’s exactly what I did. I just stood there and stared. My camera wasn’t rolling. I was just in total awe. I’ll bet the first salmon I saw had to be 3, maybe 4 feet long. … And then just to see them hover over that clean spread of gravel where their eggs are. And they stay there, they’re guarding that life on their death bed. You have to stop everything you’re doing and recognize the significance of that moment. And then you can go get your camera and take pictures. But first you have to recognize the moment.”

Millgate said she drove 4,686 miles to follow the salmon along their 850 river miles. Northwest Toyota Dealers offered up a Tundra pickup and Four Wheel Campers fitted it with a camper. She ditched any helpers and went solo.

During the course of her journey, she learned new things about people and salmon.

“What really stands out to me is not any big interview or a fact about salmon, it’s that as you move farther from the ocean to Idaho, the tone of the interviews change,” she said. “The anxiety about the loss of salmon increases the farther you get from the ocean. By the time I started interviewing people in Idaho, they’re crying during the interviews. … If anything gets here from the ocean, we are just so fortunate to see it. A lot of people now realize that.”

Idaho Fish and Game biologists estimate that thousands of chinook spawned in the Yankee Fork about 100 years ago. This year, the Shoshone-Bannock tribe fish weir at the mouth of the Yankee Fork counted 29 returning salmon.

“I refuse to wrap my head around the idea that extinction is a reality for chinook salmon,” Millgate said. “I can stand in the Yankee Fork of the Salmon River that was turned upside down for so many reasons, including gold, and see a chinook salmon still make it there. … And if they are still going to try and come back, we should never give up on trying to save them.”

Also lost with the declining numbers of salmon over the past decades is nutrients from the decomposing bodies in the mountain streams from the ocean that add to the health of the ecosystem.

“Because there are not enough naturally dying salmon in that (Yankee Fork) watershed anymore, the (Shoshone-Bannock) tribe picks up fish that are spawned out at the hatchery and lays dead salmon in the watershed to try and put back some of the nutrients into the watershed,” Millgate said. “They cut the tails off so that you know it is not a wild fish and confuse the counting process.”

Another observation Millgate made during her travels is a sense of urgency around the issue of saving the fish and what needs to happen.

“I heard a lot of people talking about collaboration,” she said. “On an issue so sensitive like salmon, we’re talking about dams and what we did a century ago and what we should try to do for this century, there’s a lot of polarization. I made sure I got perspectives from all sides of the issue. All sides said we got to work together on this. … At some point you have to compromise. We’re seeing that people are saying that. That’s significant.”

Although the Yankee Fork marks the finale for the fish, Millgate has a busy winter ahead pouring through piles of video and photos she shot to compile a documentary film on the amazing migration. Her regular episodes that started in June can be seen on her website (tightlinemedia.com/oceantoidaho/) or on her YouTube channel “Kris Millgate.”

“People have started messaging me that they are binge-watching all the episodes that started back in June. I love that,” she said. “That tells me that everything I’m doing – the stitches, the bruises, the broken camera – everything that I’m doing is worth it.”