Book review: A definitive account of the zombie apocalypse

Love it or hate it, the notion of a zombie apocalypse has played a small but persistent part in modern popular culture for more than a half-century. Artists as diverse as Max Brooks (“World War Z”), Danny Boyle (“28 Days Later”) and Robert Kirkman (“The Walking Dead”) have all put their stamps on the concept, while the TV adaptation of Kirkman’s graphic novels have brought the apocalypse into millions of homes across the world.

The creative spirit behind this continuing phenomenon was the late George Romero, whose 1968 indie film classic, “Night of the Living Dead,” continues to exert its influence on an entire subgenre.

Zombies, of course, already had an extensive history in film, literature and legend, but Romero took matters in a new direction, bringing his undead creatures out of the realm of arcane, voodoo-related rituals and into a recognizable American world of farm houses, high rises and shopping malls. Romero would go on to write and direct five more films in his “Dead” sequence, but the template was firmly established in the first.

For no reason we will ever discover, the dead have come back to life, and they are hungry. Mindless automatons driven by instinct and appetite, they also are carriers.

Victims infected by their bite become zombies themselves, setting off a chain of infections with apocalyptic consequences.

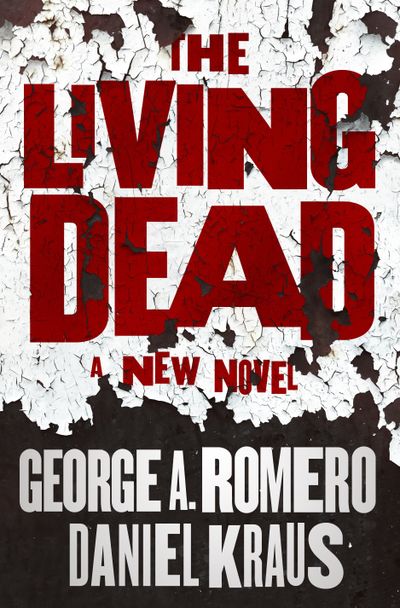

The films, in my view, are marred by too many moments of cartoonish violence; brains, blood and viscera abound in these stories. But the fundamental concepts – that the monsters who will end our human dominion look just like us, that death provides neither release nor relief, but leads only to further horrors – still retain power. Their latest incarnation comes in the form of an epic novel, “The Living Dead,” that might prove to be the definitive account of the zombie apocalypse.

Romero turned to fiction relatively late in life, and “The Living Dead” remained unfinished at the time of his death in 2017. Romero’s heirs invited Daniel Kraus, novelist and lifelong Romero fan, to complete the project.

That was a spectacularly good decision. While it is impossible to know, at all points, which writer wrote which passages, it’s clear that Kraus’ contribution was enormous and that his own narrative decisions were made in the service of Romero’s vision.

The novel, which is every bit the epic Romero intended, is divided into three “acts.” The long opening section, “The Birth of Death,” takes place in our contemporary, gadget-obsessed world and covers the origins and initial 14 days of the zombie plague.

Among the many characters in this section, five will emerge as central. Charlene Rutkowski is a pathologist whose newly deceased John Doe will become “Patient Zero” of the new era.

Etta Hoffman is a solitary, autistic statistician who will become the unofficial historian of the apocalypse. Greer Morgan is a teenager when her world is upended. She will become a warrior known as “the Lion,” a legendary figure among the diminished world of the living.

Chuck Corso, aka “The Face,” is a bland cable news broadcaster who will find himself delivering the end-of-the-world news in real time. Karl Nishimura is an officer on an aircraft carrier overrun by the dead. Karl himself is an introspective figure, a natural outsider whose ideas will help shape the nature of the human future.

The brief second section, “The Life of Death,” moves quickly through the events of the next 11 years as the remaining humans struggle to maintain a place in a world that is no longer theirs.

The long final section, “The Death of Death,” concerns the events of a single climactic day. The last 200 pages, which take place in a struggling utopian community in Toronto, carry the familiar story into new territory and toward a conclusion we have never previously glimpsed.

Despite its often grotesque violence, “The Living Dead” is, in the end, about something unexpected: the quality of mercy. History, Romero reminds us, moves through cycles, extended periods that can bring chaos and destruction before giving way to whatever comes next.

Romero’s zombies are representative of one such cycle, during which we come to see them for what they have always been: essentially tragic victims caught up in a cosmic mystery that no one will solve. By the novel’s end, the rapidly deteriorating zombies have become figures of pathos rather than terror, while the surviving humans are forced to contend with an irrevocably altered world.

“The Living Dead” expands, clarifies and concludes a tale more than 50 years in the telling and does so with wit, style and a deep sense of commitment to this frequently unsettling material.

The zombie saga in all its forms will surely be the centerpiece of Romero’s artistic legacy. Thanks in large part to Kraus, that legacy contains a significant – and welcome – new addition.

Sheehan is the author of “At the Foot of the Story Tree: An Inquiry Into the Fiction of Peter Straub.”