Too many narrators can turn an audiobook into a confusing radio play

Are audiobooks books? Certainly listening to a book is a different experience from reading. Backtracking to check details in an audiobook is awkward, and, in many cases, you don’t retain as much as you do with the printed version.

Finally, there’s the difficult-to-define relationship of listener to book: Your own imagination and interpretation have more independence when reading a book than when a narrator’s voice controls the text.

Audiobooks could be said to be a species of translation: Although true to the words, they are different in character from the original, the printed page. But they are books all the same.

Full-cast or ensemble audiobook productions complicate the matter. When different narrators take on chapters devoted to different characters’ points of view, the listener’s engagement with the book can be heightened.

On the other hand, when narrators join in together, in what are often referred to as ensemble productions, the text is usurped by performance, the book disappearing into thespian clamor.

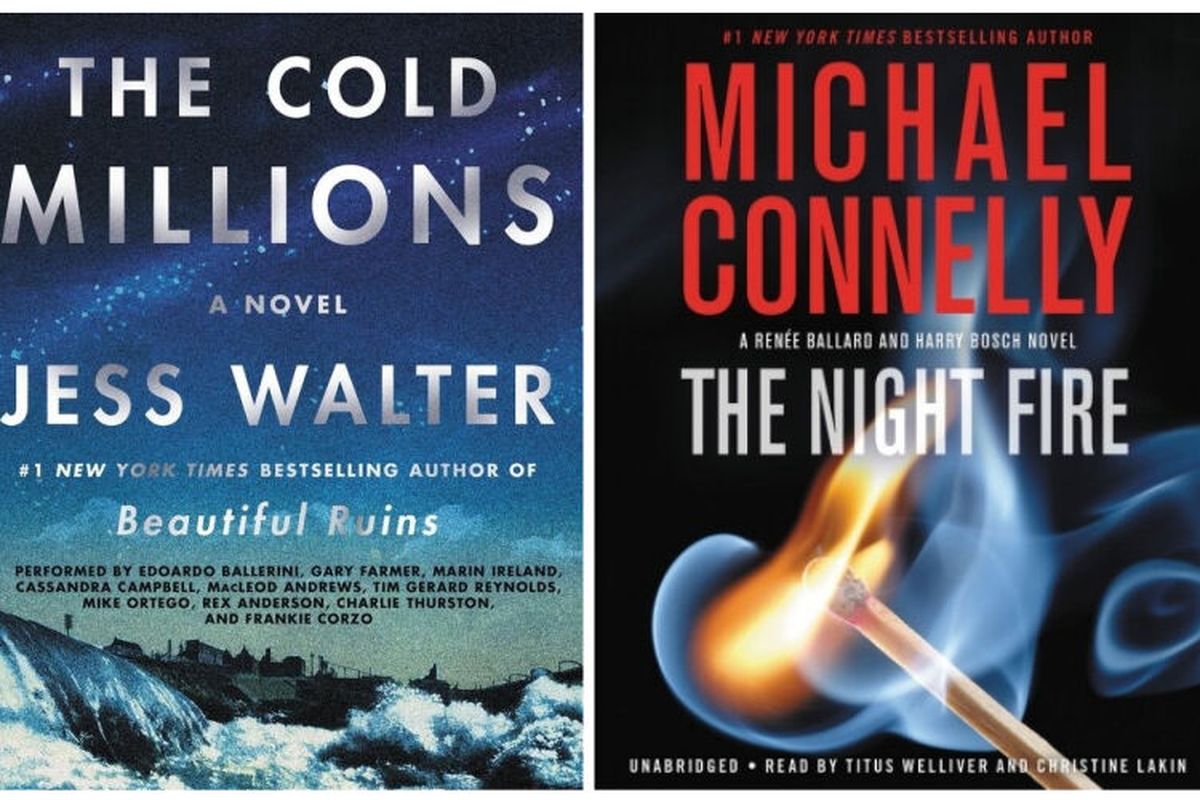

Michael Connelly’s most recent crime thriller starring Harry Bosch, “The Night Fire” (Hachette Audio), presents an example. Very Bosch-sounding Titus Welliver, a veteran of the series, is joined by Christine Lakin, who takes on the voice of Bosch’s collaborator in the LAPD, Detective Renée Ballard.

It’s clear sailing as long as each narrator delivers the chapters devoted to his or her point of view, but Bosch and Ballard appear in the same chapter, the two voices chiming in, back and forth. The story, which had been unfolding in a booklike manner, collapses into something like play acting. I could not finish listening to it.

Science fiction and fantasy tend to have more ensemble productions than other genres, no doubt because their listeners tend to welcome breached boundaries and are tolerant of pandemonium.

I have tried to listen to a couple of admired examples: Neil Gaiman’s “American Gods: The Tenth Anniversary Edition” (HarperAudio) and Max Brooks’ Audie Award-winning “World War Z: The Complete Edition: An Oral History of the Zombie War” (Random House Audio).

The first, at nearly 20 hours, is narrated by 21 people, including the author . The other, 12 hours, features celebrities including Martin Scorsese, Alan Alda, Mark Hamill, Henry Rollins and Rob Reiner, as well as a number of veteran audiobook narrators.

In both cases, I felt adrift, divorced from the page – wherever that was. I couldn’t think of either production as a book any more than I can think of a movie adaptation having anything but a remote relationship to the book on which it was based.

Evie Wyld’s “The Bass Rock” (Random House Audio), is, in contrast, a full-cast production that’s read by different narrators in sequence rather than concurrently. This works. “The Bass Rock” is one of those novels that shifts back and forth through time and from one character’s point of view to another, often without identification.

On the page, works like this can bewilder the reader before giving way to the gratification that comes with piecing the story together. Audiobooks make the puzzle more manageable by assigning a different narrator to each character’s sections. This helps the listener distinguish between different points of view.

In the case of “The Bass Rock” – a quasi-gothic concoction set chiefly in Scotland that dwells on crimes against women in three eras – Ross Anderson narrates in a fine Scottish voice as Joseph, a 17th century youth involved in helping (for a time) a young woman escape from men who would kill her as a witch.

Julie Graham and Kristy Strain take on the voices of 20th century Ruth, the unfortunate wife of Peter, a master at gaslighting, and 21st century Viv, Ruth’s step-granddaughter. Without three distinct voices to lead us through the maze of this convoluted plot, I would have been hopelessly lost.

Jess Walter’s “The Cold Millions” (HarperAudio) is another example of a full-cast audiobook that succeeds. The novel is narrated by 10 top-notch voice actors, including Cassandra Campbell and Edoardo Ballerini, each covering the point of view of one of 10 characters. It is set in the early 20th century, chiefly in Spokane, as the Industrial Workers of the World organized free-speech protests against the gouging practices of employment agents and crew bosses.

A riot ensued, and hundreds of protesters were jailed. Amid this, we follow many lives, including two brothers looking for work, a showgirl, a villainous spy, a conscienceless fat cat and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, labor organizer, feminist and, later, a founder of the ACLU. Having distinct voices deliver each section amplifies each perspective, demanding our attention and empathy.

Some lofty souls believe that listening to a book is somehow cheating – a view shaped by our nation’s piety about reading. But those of us who know better embrace well-read audiobooks as books, even when more than one voice is in play. But we do have our standards – and we shrink from ensemble productions, seeing them as monstrous hybrids of book and theater.