Shawn Vestal: Prominent African-American architect did his first work in a modest West Central home

The two-story house that sits on the corner of Gardner and North A Street in West Central may not look like a vital center of national history.

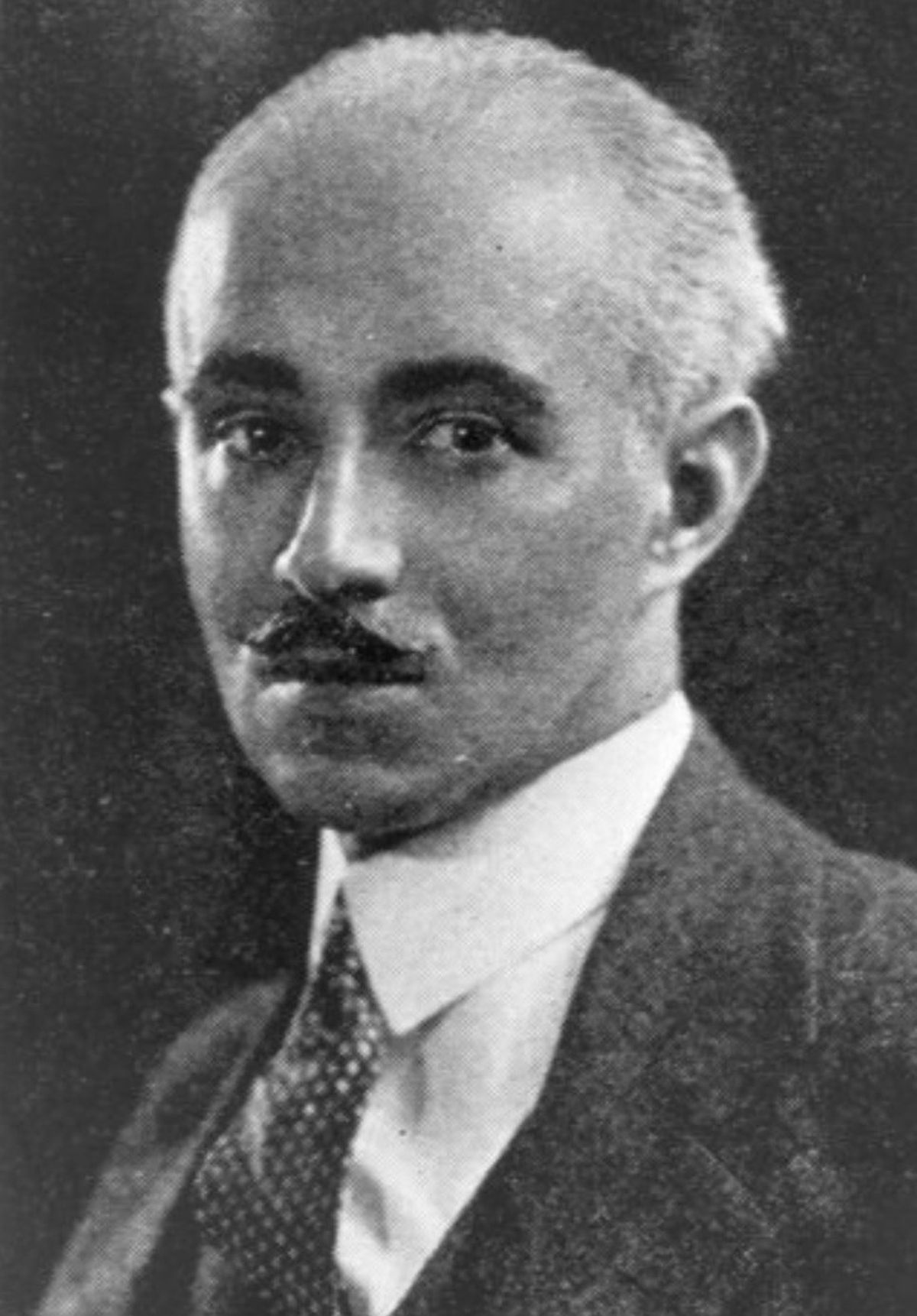

But the Cook House, as local historic preservationists know it, stands at the intersection of several pathways in the story of African Americans in the Inland Northwest. It was the first building designed by one of the most prominent Black architects of the early 20th century, Julian Francis Abele – a fact only recently unearthed by local preservation advocate Kevin Brownlee.

Over the course of an illustrious career, Abele designed hundreds of buildings back east, including major civic works in Philadelphia and on the campuses of Harvard and Duke. He had spent a few years in Spokane after graduating from college, and he designed the home at Gardner and A Street in 1904 for his sister, Elizabeth Cook.

She had come West in the late 1880s with her husband, John F. Cook III, who became a postmaster and pharmacist in Bonners Ferry, Idaho.

Coincidentally, the Cook House was built next door to the home of John Byron Parker, an African American man who ran a successful downtown barber shop. That period, from the late 1800s through the early 1900s, was a time when Spokane’s Black population – while small – was growing rapidly, driven in part by migration from the South.

But a part of that migration also included people like Abele and the Cooks, who came from wealthy, prominent families in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.

The Cook House, and the historical echoes that surround it, is a fitting story for the month in which we celebrate and recognize the often-overlooked history of Black Americans.

Its local significance was unknown until last year, when Brownlee, a longtime member of the Spokane Preservation Advocates board of directors, discovered the link in an online record of Abele’s application to be admitted to the American Institute of Architects from 1942.

Listed among his architectural accomplishments – which include the Philadelphia Art Museum and the chapel at Duke University – was the modest two-story home he had designed for his sister.

“It felt like Spokane really had this brush with genius,” said Brownlee, who wrote a piece about it in September for the Preservation Advocates. “The fact that the house here was the first structure constructed from an Abele design really makes it important on a national scale.”

Spokane, not Paris

Abele was born in 1881, the youngest of eight children in a family that Smithsonian Magazine called “a fixture in Philadelphia’s African American aristocracy.”

He was a descendant of the Rev. Absalom Jones, a prominent abolitionist and founder of St. Thomas Episcopal Church in 1794. His grandfather, Robert Jones, founded the Lombard Street Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia.

One of his brothers was a doctor; another was an engineer. Two other siblings became successful as sign makers. As Elizabeth Cook’s great-granddaughter Susan Cook told Smithsonian Magazine in 2005, “Julian’s is not a rags to riches story.”

An outstanding student, he enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania and studied architectural design; in 1902, he became the first Black graduate of what is now Penn’s School of Design. His time at the school was marked by his winning several academic honors, all while working at an architectural firm in the city.

It was in the years immediately following graduation that Abele came to Spokane. Little is known about that time, and many accounts of his life claim Abele was studying at the l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, given how important French architecture and the Beaux-Arts style would become in his work.

But Dreck Spurlock Wilson, the author of the 2019 Abele biography, “Julian Abele, Architect and the Beaux Arts,” puts him in Spokane during that period. Brownlee, in his account for Spokane Preservation Advocates, quotes Wilson’s book: “From 1903-1906, Julian resided closer to the Spokane River than La Seine.”

It might seem strange that Abele, with such firm foundations and bright prospects in Philadelphia, would move to rough-and-rowdy turn-of-the-century Spokane. But his sister had preceded him by a few years, coming out to Bonners Ferry with her husband.

In fact, it’s possible that Abele came first to Idaho. The Smithsonian piece on Abele reported, “After graduation, Abele is believed – records are spotty – to have traveled to Idaho to help his sister Elizabeth, whose husband had recently accepted a position as a small-town postmaster.”

‘The only man of color’

Like Abele and his sister, John F. Cook III came from what some termed the Black aristocracy. The son of John F. Cook Jr., a wealthy educator, public official and civil-rights advocate in Washington, D.C., Cook earned a pharmacology degree at Howard University in 1888.

He arrived in Bonners Ferry four years later, according to an account from the Boundary County Historical Society.

“He quickly realized he was the only man of color in town,” it said. “Not to be discouraged, he opened a drug store on Main Street in August of that year, giving H.W. Gate’s Drug Store some competition.”

Cook was also the town postmaster, and became involved in civic affairs. On a visit back east in 1894, he married Elizabeth Abele.

Upon their return to Idaho, “they were given an unexpected charivari by the town people,” the historical society said. “When the train pulled into the station, they were met by a crowd of 100 cheering men and boys. They were conducted to a waiting sleigh and literally pulled by the crowd to the International Hotel for a celebration!”

It is not clear how things evolved between the Cooks, but Elizabeth began living in Spokane while her husband remained in North Idaho. Three of her four children were born in Spokane; she would return to Philadelphia in 1906, two years after the home her brother designed was built in Spokane’s second Nettleton Addition, and divorced Cook after that.

John Cook’s fortunes worsened and worsened over the years. He lost his position as postmaster and fell into financial trouble. Late in his life, a newspaper account described him as “sick, impoverished and friendless, except for the kind ministrations of Henry Ferbache, the hotel clerk.”

A prominent resident of Bonners Ferry, D.P. Dayton, was quoted in 1931 urging locals to be good to Cook: “We never heard the story of how a colored man came to northern Idaho, became the postmaster of the largest and most important town in the north, but such he was, and served faithfully and well for many years. Let us all drop our feelings of racial aloofness, come down to earth and realize that the blood of all mankind is red, and go and visit the old pioneer.”

Cook died in 1932. The historical society said he was buried at Grandview Cemetery in Bonners Ferry, where there is “no grave marker to be found.”

‘The most accomplished’

By the time Elizabeth Cook and her children returned to Philadelphia, her brother’s career as an architect was taking off.

He was the third African American to be formally trained and licensed as an architect, according to Wilson. Upon his return from the West, he had been hired by the all-white firm of architect Horace Trumbauer; he was head designer by 1909.

“Abele was not the first black architect in the United States, but he was probably the most accomplished of his era,” according to Smithsonian Magazine. “Abele’s race, coupled with his self-effacing personality, meant he would not be widely known during his lifetime outside Philadelphia’s architectural community.”

It was customary for designs to be attributed to the firm, and not individuals, which also complicated efforts to identify his work. Still, Wilson credits Abele with designing more than 100 large, cut-stone buildings between 1906 and 1950.

Among his most well-known works is the Philadelphia Art Museum – famous for the huge stone steps that Sylvester Stallone surmounted at a sprint in “Rocky II.”

He designed, or contributed to the designs, of hundreds of other buildings, including structures at Harvard University and Gilded Age mansions in Pennsylvania, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington, D.C., according to Brownlee.

He designed 39 buildings for the brand-new Duke University, including the famous Duke Chapel – all without ever being allowed to see his work brought to fruition on the whites-only campus.

More than 20 buildings he designed are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

His brief time in Spokane doesn’t figure very large in his architectural legacy, perhaps. But it figures more prominently as a piece of an important era in the city’s African American history – a time when some of the city’s most important, enduring Black institutions were formed.

As Black Americans fled the South for other parts of the country in the late 19th century, some came here looking for work in the mines, or as stonemasons, or on the railroads. The Black population rose from an official count of three in 1880 to1,170 in 1910.

There were also business owners, such as John Byron Parker, who lived next door to Elizabeth Cook and whose barber shop at the California House sat at the current site of the Looff Carousel.

Peter Barrow Sr. arrived here in 1889 from Mississippi and started an apple orchard that employed more than 100 African American workers, according to an article by Jim Kershner in the Washington State University magazine. He helped establish Calvary Baptist Church and became its pastor.

Another Mississippian, Emmett Hercules Holmes, came here and eventually became the county’s deputy treasurer. He established the Bethel A.M.E. Church in 1890.

The churches would become central to Spokane’s African American community. Three decades after their formation, in 1919, Spokane’s chapter of the NAACP was formed.

The Cook House is now a rental property, with a chain-link fence around the yard. It’s not marked by any plaque, and you’d have to be someone like Kevin Brownlee – who lives in the neighborhood and sometimes passes by the house whose history he helped discover on his walks – to recognize its significance.

But if you walk past it today, you’ll see a small, informal emblem by the front door that takes on extra resonance when you know the story of the man who designed the home: A Black Lives Matter sign.