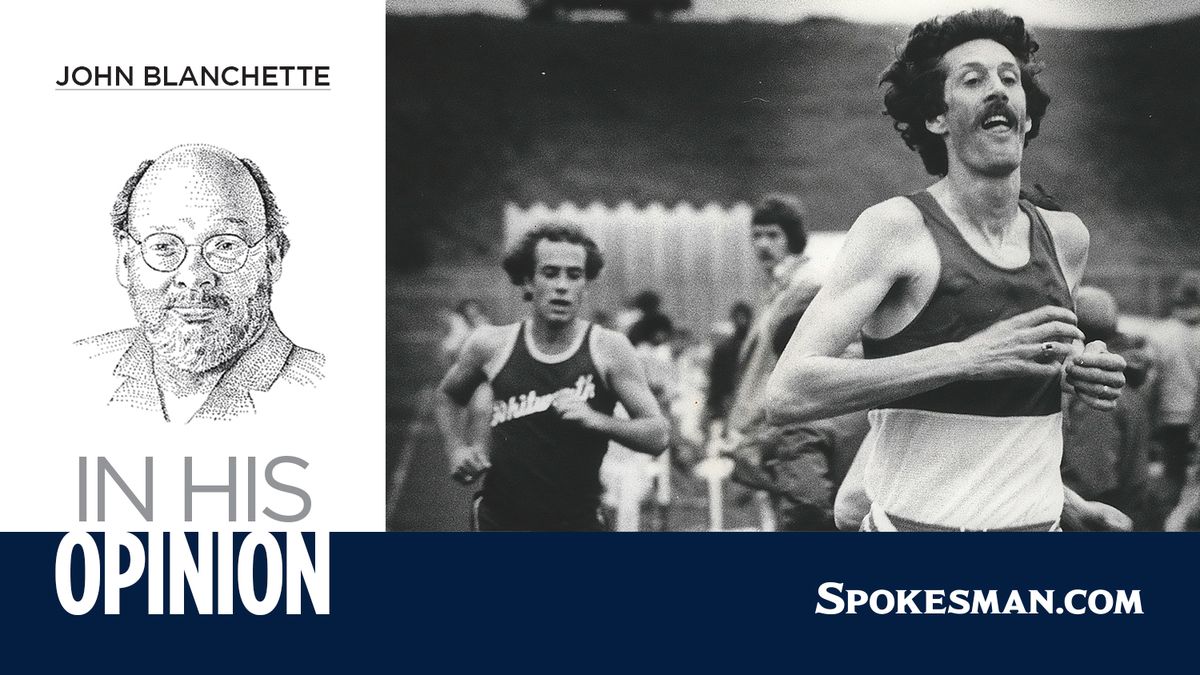

John Blanchette: Whether with his feet or his wit, legendary runner Bob Maplestone was hard to beat

Back when indoor track had a pulse and a national audience – and this was 50 years ago – the Oregon Indoor in Portland was an important stop where the longer races would draw legends both made and in the making: Steve Prefontaine, Jim Ryun, Gerry Lindgren and Frank Shorter, among others.

But in 1972, the mile was won by Bob Maplestone of Wales and what was then Eastern Washington State College, who had motored over with coach Jerry Martin.

“It was a big night for him,” Martin said. “There was a bunch of other foreign athletes at that meet and those guys stayed out and drank until 3 in the morning – and then they went out and ran. I wound up driving back to Cheney and he slept all the way.”

Run hard, fun hard.

That, utterly simplified, was the essence of Bob Maplestone, who died Saturday after suffering a heart attack at his home in Edgewood, Wash. He was 74, retired from a career of teaching engineering at Highline Community College.

The building blocks of this area’s great running reputation are many: Lindgren the prodigy on the world stage and Rick Riley’s impressive encore, a lineage of engaging coaches that began with Tracy Walters, Don Kardong’s Bloomsday brainstorm, high school dynasties at Mead and North Central and even Henry Rono and the Kenyan wave at Washington State that brought Olympic medalists into our midst.

Under-remembered are some prominent characters who carried on the torch, and Maplestone was very much a character – on top of being a sub-four-minute miler and national champion.

He won four titles in Eastern’s NAIA days, indoors and out, at a mile or 1,500 meters. But he also did the grunt work – running and winning everything from 880 yards to 6 miles at the old Evergreen Conference meets, with teammate Rick Hebron winning what Maplestone didn’t.

But he wasn’t just knocking off guys from Southern Oregon and Fort Hays State.

During that ’72 season, he won the San Diego Union Indoor mile in 3:59.5, a British record – if only he’d bothered to send in the paperwork. Two months later, he took down Ryun in a Drake Relays record 4:00.4. At the National AAU championships in Seattle, his 3:39.7 in the 1,500 was a Welsh record and earned him a spot in Britain’s Olympic trials – where, alas, he admitted that he “just did everything wrong. I choked.”

Which was Maplestone frankness to the nth degree.

Yet his achievements were startling for someone whose running career seemed to unfold by accident – if hard work is ever an accident.

What little he dabbled in the sport as a Cardiff schoolboy stopped at age 15, and for the next five years he worked as a toolmaker and served in the national guard until taking another crack. His first timed mile: 4:38. But by 1970 he’d run himself onto the Welsh team for the Commonwealth Games, and cast an eye toward America to get truly serious.

Problem was, he was already 24, and the NCAA had age limitations in place for international athletes. The University of Idaho – where track was then an afterthought – had him come anyway, only to learn he wouldn’t be eligible for championship meets. With a rescue from Washington State coaches Jack Mooberry and John Chaplin, Maplestone found his way to Eastern and carved out an instant identity.

“The Brits and Irish guys and Aussies, they were always more laid back than the Americans,” said Riley, a regular training partner. “They raced and trained hard, but they had a more relaxed approach to life. That was Mape.”

At 6-foot-4, with an expressive face, mischief in his heart and a Tom Jones accent, he was also a campus celebrity – and instigator. Which brings us to the wolf story.

It was a meet at what was then the Oregon College of Education in Monmouth, “which Mape discovered to his dismay was the only dry town in Oregon,” said Jeff Jordan, former Spokesman-Review sports editor and Eastern’s student sports information director at the time. The two walked into a student union that was completely deserted – save for a stuffed wolf, the OCE mascot.

“Hey, mate, we ought to take that home to Cheney,” Maplestone nudged.

Reason did not prevail.

The wolf was ferried to the trunk of a rental car. By the time they made it back to Cheney, Jordan was fully swept up in the caper and “had the bright idea to take a picture and put it on the front page of the Easterner,” he said.

“Three or four days later, there’s a letter from the president of OCE saying, ‘Hey, glad you have the wolf. Just send us a check for $4,000 and we won’t file charges.’ So I have to drive down to Monmouth with the damned wolf. But it was Mape’s idea. He was such a captivating guy.”

And even more competitive.

Riley remembered piling into Maplestone’s old station wagon with Hebron and Spokane Falls runner Lucas Oloo for a drive to Bakersfield, California, and the 1973 AAUs. Several breakdowns occurred, and once at the motel, Maplestone “pulled out his tool chest and rebuilt the camshaft or something,” Riley said. “Then he ran a 3:59 mile.”

And both Riley and Martin summoned the memory of a 1977 half-mile race in Cheney with Steve Kiesel – now coaching at Mead – for being among the best they’ve seen.

“He was 30 by then and coaching at Highline, and he’d already won the mile in 4:01,” Riley recalled. “Kiesel was trying to get by him in the final 50 and Mape just kept him on his shoulder and boring him out – I think Steve wound up in Lane 5. That was his toughness.”

There wasn’t a lot of mileage left in his legs, but Maplestone knew by this time he didn’t need to keep running, as longtime friend Bob Payne – another former S-R sports editor – wrote in an email:

“I always sort of thought Bob was absolutely relishing his ‘new’ life … in contrast with the frankly rather regimented and predictable life in the old country, in a Wales where men and boys tended to be channeled into the same jobs their fathers had, whether it be mining or agriculture or whatever. Running absolutely (and, indeed, literally) opened his world.”

In return, Bob Maplestone let people into his.

They rarely felt like leaving.