Solving for ‘R:’ EWU clinic uses ultrasound technology to help children with speech disorders

With an ultrasound probe held beneath his chin, 12-year-old Jack Felker cycled through some of the most common R sounds in American English.

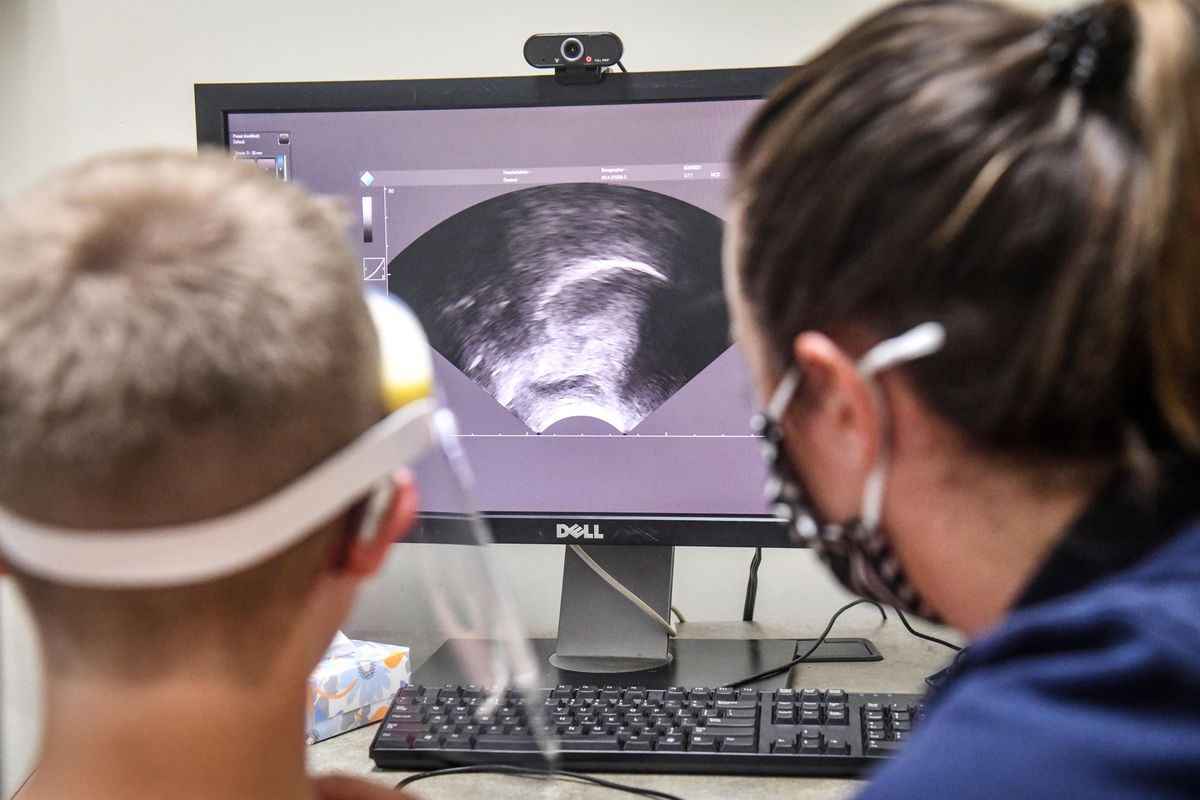

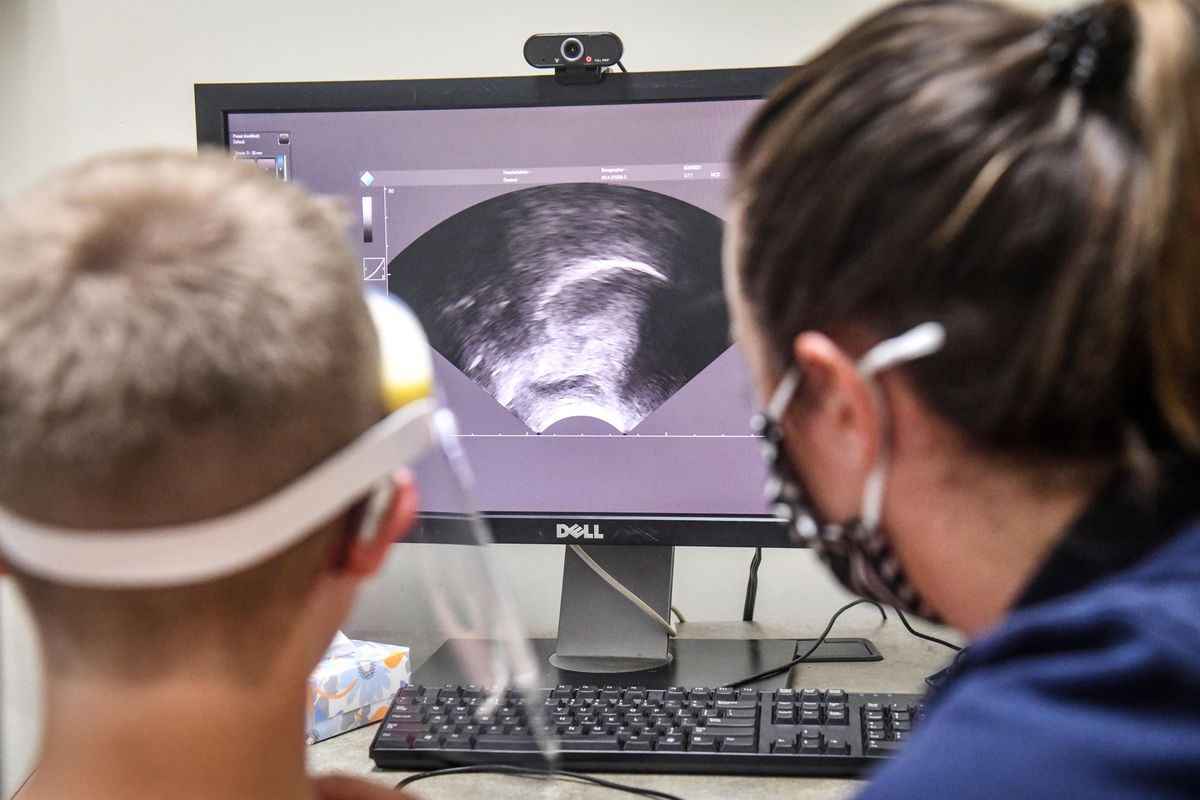

He started off by repeating single sounds five times, before moving to strings of words, from “are” and “car” to “her,” “bear” and “sir.” All the while, a monitor in front of Jack showed a sonogram of his tongue in action, giving him a live look at how he physically shaped the sounds with his mouth.

R sounds have historically been troublesome for Jack due to his hearing loss, said his mother, Krista Felker. By the end of the two weeks, however, she noticed significant improvement – particularly in the beginning and middle of words.

“I think it’s amazing,” Krista Felker said, “because when he’s with a normal speech therapist, with any of the sounds, they can’t look inside his mouth to see what he’s doing wrong. They can try different tactics, but if you don’t know what’s going on inside their mouth, you can’t help them.”

Jack was one of eight children who participated in the ultrasound speech clinic facilitated by Hedieh Hashemi Hosseinabad, an assistant professor of communication sciences and disorders at Eastern Washington University.

Assisted by six graduate students from EWU and Washington State University, Hosseinabad evaluated the children during 45-minute sessions over a two-week period at the Health Sciences Building of EWU’s Riverpoint campus in Spokane . The clinic was focused on helping children struggling to say their Rs, though Hosseinabad said the technology can be applied with other sounds.

Hosseinabad learned to use ultrasound to address residual speech errors in children during her doctoral studies at the University of Cincinnati. She requested an ultrasound probe when she was hired in 2018 as part of her faculty startup fund.

This was the first year EWU has hosted the ultrasound clinic, which, according to Hosseinabad, is the only one in Washington state and the surrounding area.

“I have seen tremendous progress from Day One when they come in and then Day 10 when they left with a good tongue shape,” she said.

Traditional speech therapy has involved using mirrors or other visual indicators to help correct errors. In some cases, however, the issue is taking place inside the mouth, Hosseinabad said.

“A lot of children that have difficulties with producing R, they can benefit from traditional therapy, but because R is a difficult sound, some of those children cannot get it right with just using those feedbacks that are done in clinics without using any other sort of feedback,” she said. “Using the ultrasound, that would be helping them to have a good picture of what’s going on inside their mouth.”

The clinic’s initial sessions helped establish a baseline for each child, Hosseinabad said. She said R sounds are particularly complex since there are more than 20 ways people can physically produce them.

To help with shaping, clinicians showed the children the different parts of the tongue on the sonogram, as well as a mouth model.

“We try to work on their hearing too because a lot of these children who have those residual sound errors don’t have a good perception of their correct versus incorrect sounds,” Hosseinabad said. “They say something like an ‘er’ and then they’re like, ‘I don’t know if that was a good one or a bad one.’ ”

The clinic came to a close Friday. Hosseinabad said she does not anticipate hosting another one until next summer due to teaching and research duties. One of her research topics involves using ultrasound biofeedback treatment to help address speech disorders in children caused by cleft lip and palate.

The ultrasound probe used with the clinic cost about $9,000, Hosseinabad said. She is applying for funding to acquire another one, which would allow clinicians to address more children.

The kids evaluated at this year’s clinic went through traditional therapy for a significant time without success in producing R sounds, Hosseinabad said. Most were referred to the program by their school’s speech-language pathologist.

That includes Jack Felker, who has taken in-school and private speech therapy since he was around 4, according to his mother. The setup at the Health Sciences Building allowed Krista Welker to watch her son’s progress behind a one-way mirror.

“It’s been really cool to see what he’s doing in his mouth,” she said, “and for him to learn from students that are going into this field and are invested into kids learning to speak properly.”