Ice, ice maybe? Idaho’s ‘Glacier Hunter’ and geologists say there are more glaciers out there

IDAHO FALLS – Call him the Glacier Hunter.

About mid-September each year, Collin Sloan, of Boise, sets out into the mountain wilderness tracking the elusive Idaho glacier.

Sloan is convinced that Idaho has more glaciers than just the one officially recognized, the Borah Glacier. It was Sloan’s efforts that pushed the Forest Service and other government entities to officially recognize the Borah Glacier tucked into a shaded cirque on the north side of Idaho’s highest peak. Although he didn’t find the Borah Glacier, his role in getting it legitimized has pushed him to seek out other giant ice formations. The Borah Glacier was officially named in February.

“I believe there are more glaciers, and I’ve continued to research other locations since 2015,” Sloan said. “I’ve got one that’s very remote, and I think that will be the largest glacier in the state. I was there two years ago. … I’ll get the Forest Service involved, and we’ll name that one, too. That’s my hope.”

The story of the Borah Glacier goes back to 1974 when Bruce Otto, a geology student at Boise State University, discovered the glacier while doing a project for his geomorphology class. He and his professor, Monte Wilson, were joined by eight geology majors to study the glacier the following summer. The Challis National Forest helped by helicoptering in equipment.

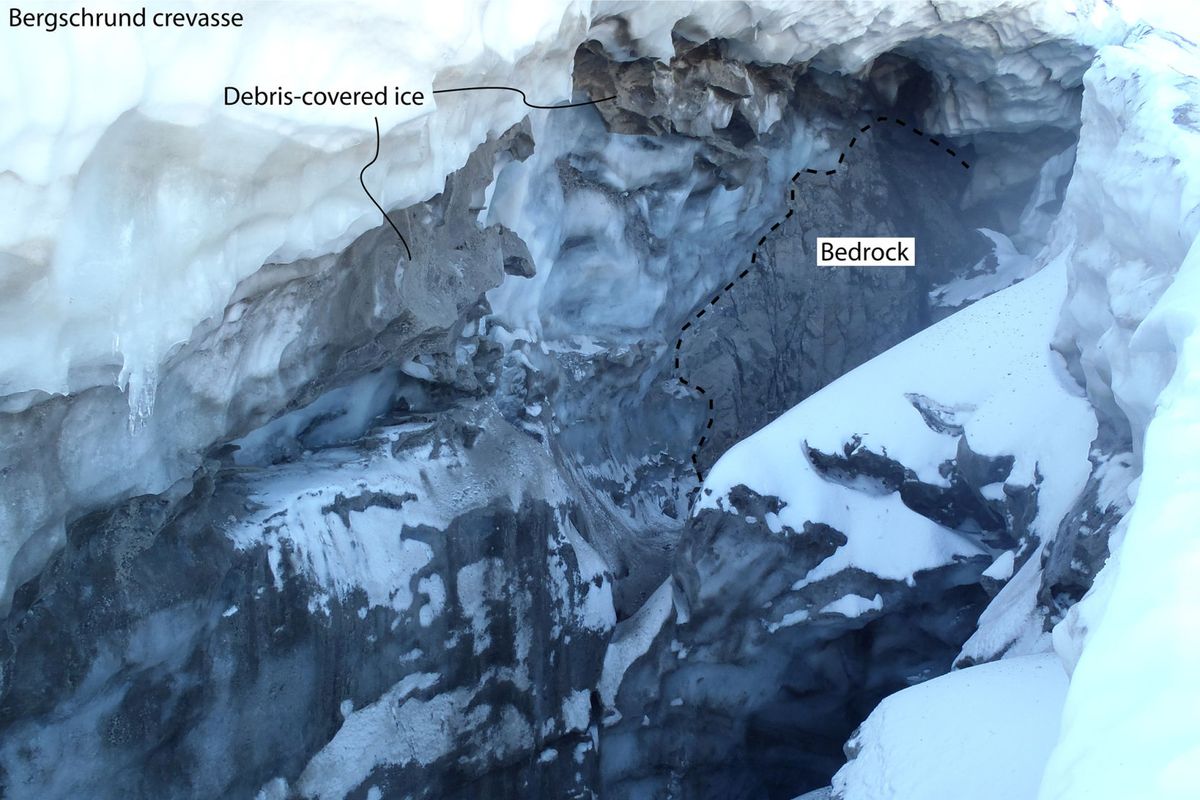

“The first year I was there, the bergschrund was open,” Otto said of the large crevasse at the top of the glacier. “I went all the way down inside the full length of a 150-foot rope.”

Otto said some sections of the glacier were measured at more than 200 feet thick. The surface size of the glacier is about 30 acres, although its lower two-thirds is carpeted with a layer of rock debris.

In 2015, at the urging of Sloan, the Forest Service sent out geologist Josh Keeley with another crew to study the glacier.

“It was honestly a dream come true for me because I had just graduated two years prior with my master’s in geology, and I had taken my undergraduate degree at the University of Rhode Island where I studied under a glacial geologist,” Keeley said.

What Keeley found 41 years after Otto’s study was an intact glacier still more than 210 feet thick and still moving at about 30 inches per year.

“The furthest upstream crevasse that I went into was 40 feet deep,” Keeley said. “At the bottom, it was a frozen meltwater pond. So even that wasn’t the true bottom. I was so surprised to see how clean that ice is in that upper crevasse.”

Keeley said a healthy glacier is basically a conveyor belt that brings debris from all edges of the glacier. Snow and ice higher in elevation accumulates and turns to ice and moves down the slope pushing up debris. Keeley said the Borah Glacier “is in stasis, it’s moving inside but not growing” beyond its current size.

Otto and Keeley said it is easy to mistake the glacier for a permanent snow patch because most of it is hidden under a layer of rock debris. But the rock debris and the shadow of the deep cirque surrounding the glacier protects it from melting out.

“I’ve long suspected that there are other occurrences like the one I’ve found,” Otto said of the possibility of other Idaho glaciers. “They’re buried under rocks and no one has paid any attention to them. There’s a reasonable hope of success. I still think that.”

That hope keeps Sloan on the lookout.

“I’ve always been a Google Earth geography maps guy,” Sloan said.

Sloan said he looks for similar features like those found on the north side of Borah Peak with what looks like a permanent snowfield. He won’t say where, but he said he has found at least one other glacier in Idaho.

“Let’s keep that close to the vest for now,” he said.

Otto is more forthcoming.

“I can tell you one place where I know there is glacial ice and that’s up in the Boulder Chain Lakes area in the White Clouds,” Otto said. “There’s a feature up there in the upper part of that basin called The Kettle. Kettles are a function of melting ice. I’ve been there and those kettles are very active and there’s ice exposed in the walls of these deep pits. There’s clearly glacial ice there.”

Otto said this glacial feature has the potential of being “as big or bigger than the Borah Glacier.”

Otto said he doesn’t anticipate the renewed interest in glaciers sending hundreds of people into the Idaho wilderness to hunt for glaciers, although most, are “backpackable.” But Sloan vows to point the way for geologists to study his next candidate.

Otto admires Sloan’s enthusiasm.

“When I finally figured out what he was up to and what he was trying to accomplish, and the motivation behind it, I kind of took a liking to the guy and helped him out as much as I could,” Otto said.