Blaine Harden’s ‘Murder at the Mission’ is history revealed, not revisionist history

For years, the story of how Washington and the Pacific Northwest became part of the U.S., taught to school children, college students and passed through generations, was a lie. That myth, based on the life and death of missionary physician Marcus Whitman and his wife, Narcissa, gave rise to a venerable university in Walla Walla in his name and created a national site at their failed mission.

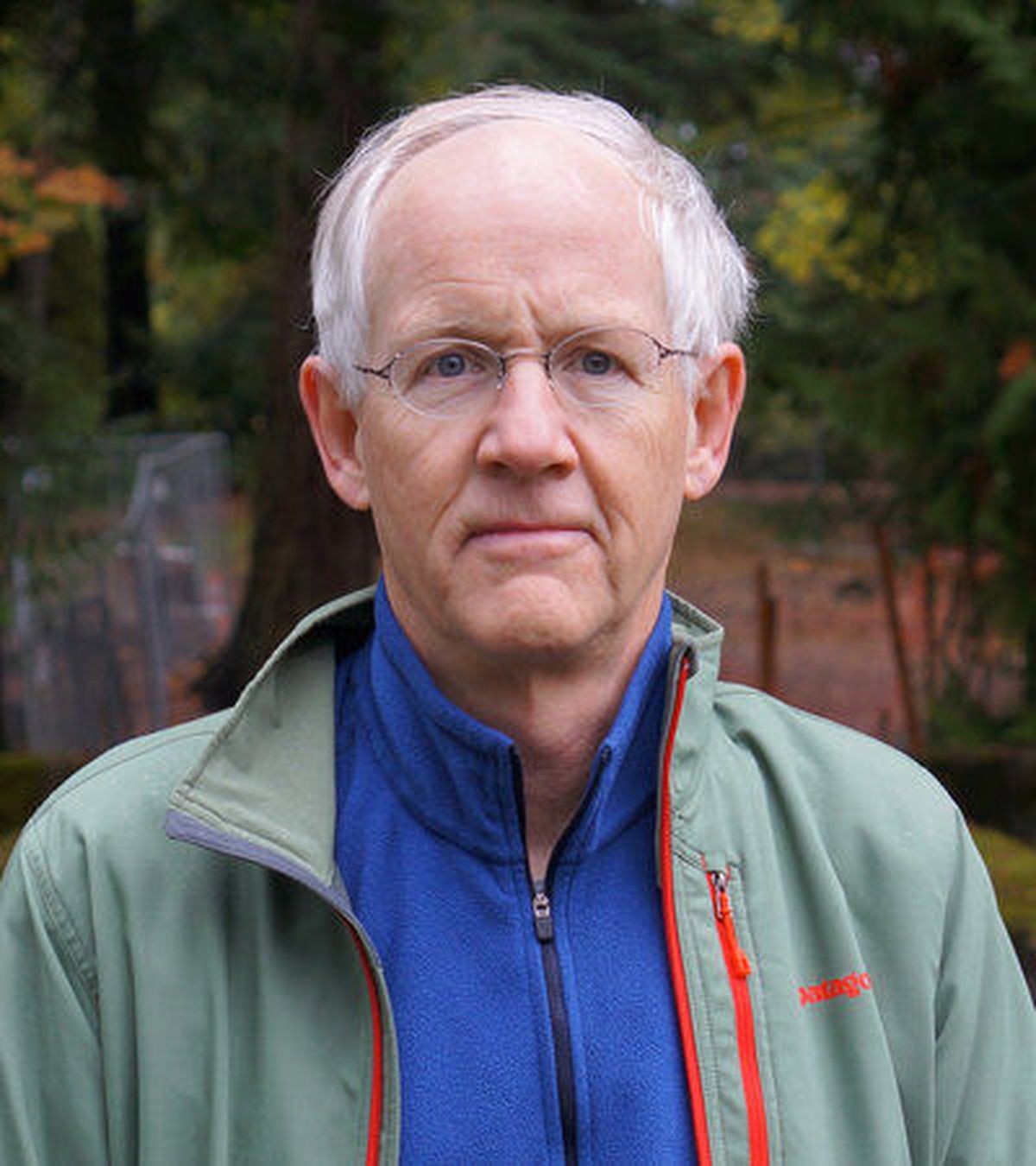

Author Blaine Harden sets the record straight in “Murder at the Mission,” a richly detailed and expertly researched account of how a concocted story, invented by another missionary to save his own reputation and used to drive collections at the Sunday church offering plate, became a part of American legend.

The story of Marcus Whitman, however, goes beyond correcting inaccuracies that still find places of honor in this state and haunt the history of the region’s Native American communities. It is a cautionary tale of how the quest to cast strong personal beliefs in a good light can make even the most educated folks gullible fools.

How the Whitman myth, including a false solo ride across the country to save the Pacific Northwest from a British takeover and the couple’s “massacre” at the hands of “savage Indians,” is not a far reach from the 21st century conspiracies of Q-Anon and stolen elections.

Indeed, the stories of America’s westward expansion are rife with hokum. Harden puts the Whitman story in perspective of other tall tales of the American West, which venerated white expansionists and castigated Native Americans. Such stories elevated white supremacy and made killing Native Americans entertainment suitable for family movie matinees.

The real importance of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, and their fellow missionaries Henry and Eliza Spalding, perhaps stopped with their arrival via the Oregon Trail. Narcissa and Eliza marked the first white women to complete the journey alive. That inspired an influx of families to venture west and invade the lands known as “Indian Country” inhabited by the Cayuses and Nez Perce.

Both tribes initially welcomed the Whitmans and Spaldings, allowing the newcomers to set up missions in tribal land. The tribes, however, were less interested in the missionaries’ staunch Calvinistic Presbyterian doctrines. The Whitmans were pious and Henry Spalding cruel – known for whipping Native men and women into submission for their perceived “sins,” which were little more than cultural differences.

The missionaries’ attempt to convert the tribes to the religion of white Protestants was failing so badly that the American Board of Foreign Missions considered closing them down. Marcus Whitman set out on his cross-country journey, not to save the Oregon Valley for the U.S., as myth would later have it, but to save his own job and reputation.

As Whitman returned, so did the white invasion. They brought with them diseases such as the measles, for which Europeans had stronger immunity and Native Americans had no defense. The tribal members began dying from a disease that did not seem to kill as many white people. The Cayuses turned to Whitman, the physician, for help. Whitman, however, could not save Native American lives.

Whitman also refused to pay rent or give back to the Cayuses the successful bounty his ever-expanding mission land produced. Whitman, like other European protestants, saw the land as theirs to command. The Native Americans were merely obstacles to the intruders’ claims of Manifest Destiny. Finally, the tribes had enough of Whitman’s piety and Spalding’s abuse. They did what they did to their own failed medicine men: the Cayuses killed the Whitmans.

The tribes also wanted Spalding dead, but he escaped with the help of a local Catholic priest. Spalding’s gratitude, however, was short-lived. Spalding, whose mental stability had been questioned by other missionaries in the region, would go on an anti-Catholic, anti-Native American rant lasting years. He accused the priest who saved his life of planning the Whitmans’ death, which became a storied massacre.

Spalding’s concocted accusations were so incredible, many newspapers here refused to print them. To combat lack of attention, Spalding started his own publications, like conspiracy theorists today starting up a website or social media account to spread falsehoods. Spalding’s ravings caught the attention of the Rev. George Atkinson, who would become known as the Father of Education in the Pacific Northwest.

Atkinson persuaded Protestants in powerful East Coast institutions to repeat the fabrications, by this time that Whitman rode solo across the country to Washington, D.C., to warn President John Tyler of a British plan to take over the Pacific Northwest.

Though this fictitious White House meeting was never recorded in any official archives, the story persisted that Whitman saved Oregon for the U.S. The story took off like a western wildfire, and Spalding even got it published in official Congressional records.

Despite being debunked by historian after historian through the years, the story ended up in the Ladies Home Journal, the New York Times and the Encyclopedia Britannica. The story would die, then rise again. After Whitman College was founded in the doctor’s memory, it struggled to survive.

President Stephen B.L. Penrose found new life for the fantastic story and its ability to raise money in church collection plates to save the college from financial ruin. Meanwhile, the Native Americans suffered, branded heathens and savages. The Whitman killings became justification for taking of Native American land and breaking treaties.

Harden’s writing is colorful and sharp, weaving a story about how lies can grow into myths and produce long-suffering consequences. The book even offers surprise twists on efforts to right history on the campus of Whitman College and the rebuilding of the Cayuses tribe.

“Murder at the Mission” presents an unsettling, unabridged history of the American West. Some might call “Murder at the Mission” revisionist history. That would be as untrue as the fictional Whitman story. Harden’s deeply researched book, often from the letters and words of the principle figures themselves to rebuke lies told on their behalf, is not history revised. “Murder at the Mission” is history revealed.

Ron Sylvester has been a journalist for more than 40 years with publications including the Orange County Register, Las Vegas Sun, Wichita Eagle and USA Today. He lives in Kansas.