We the People: ‘All men’ in the Declaration of Independence wasn’t always interpreted literally

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens

Today’s question: Why is the Declaration of Independence important?

Drafted by Thomas Jefferson in 1776, the Declaration of Independence served not only as a document proclaiming national sovereignty from Great Britain, but spelled out basic rights for all American citizens .

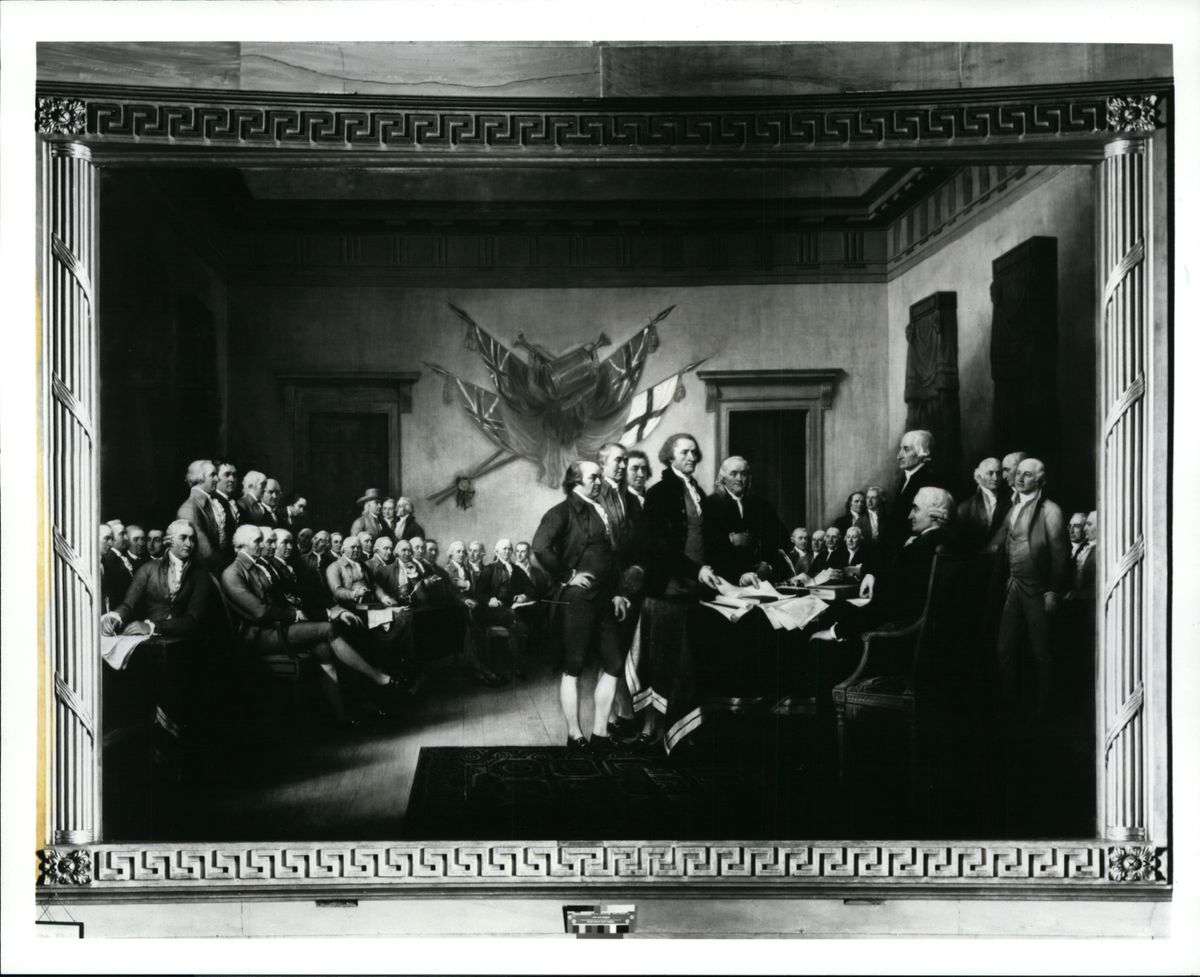

The signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776 was a pivotal event of the lengthy American Revolution that would eventually culminate into the official founding of the United States by 1781. Some provisions within the declaration remain relevant and even contentious issues in our modern society. Additional measures failed to account (at least explicitly) for the rights of certain individuals until much later.

Among a few of the most quoted pieces in the Declaration is the statement “all men are created equal.” Like several other assertions in this document, its meanings are broad and open to a certain amount of ambiguous interpretation. Even with such broad statements, however, it would seem to imply equality to every man is among the “unalienable Rights,” including “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

There is the immediately obvious omission of women from this statement, but this still does not adequately explain why even all men have often experienced anything but equal treatment since U.S. formation.

If “all men are created equal,” then institutions like slavery should not have been allowed to endure for nearly another century after the Revolutionary War, right? Was African enslavement at least of the men), then, not a direct violation of the Declaration of Independence that 56 members of the Second Continental Congress signed, including author Thomas Jefferson?

Although the statement appears rather unambiguous, the answer to these questions is not quite so simple. During the late 18th century, the newly formed U.S. was still largely rural in population and slavery remained a prominent institution to increase agricultural output. It is also common knowledge that even forefathers like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owned slaves, indicating just how socially acceptable it was at the time and why “men” would have been assumed to imply Euro-American males, specifically, to period readers.

Similarly, various groups of tribal people experienced constant oppression during the early period of American formation and well into the next century, with frequent forced (and often violent) removal from their lands during westward expansion. Such acts are evidence the phrase “all men” did not include males of Indigenous descent, either. Yet, what guaranteed that such subjugation of non-white men was permitted for so many years while numerous Anglo-Americans remained relatively free of punishment?

Not only did predominant racist ways of thinking among Anglo-Americans make it easier for them to look the other way at inequality, but citizenship was a central basis for justifying who qualified legally as “men.” Although early practices of African enslavement for much of the 17th century were less racially defined and showed such forms of slavery were not inevitable, slavery became much more sharpened along these lines around the turn of the 18th century, long before the American Revolution.

The question of citizenship, however, is key to explanations for disparities between statements within the Declaration of Independence and actual practices immediately after. As with most legal language, one must define exactly what even a seemingly obvious reference like “all men” signifies.

As it turned out, citizenship was hardly mentioned at all in either the Declaration of Independence or the original Bill of Rights, which followed just over a decade later. Section 2 of Article IV in the U.S. Constitution does state, “The citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.” Some mention of citizenship does exist, but this broad provision does not elaborate on who even constitutes a citizen.

Thus, this opened the door for countless interpretations of who was created equal and promoted the oppression of African Americans, Indigenous people and women alike.

Citizenship for each of these groups would only occur at various points over time and achieve legal guarantee through separate pieces of legislation. The first of several key pieces of legislation was the 14th Amendment in 1868, which abolished slavery and officially granted full citizenship, as well as rights and protections outlined in the original Constitution, to African Americans.

The 15th Amendment, then, granted them the right to vote in 1870. Speaking of the right to vote, passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 awarded this privilege on a national level to women, who had been more explicitly omitted from the Declaration of Independence. The 19th Amendment guaranteed no citizen could be prevented from voting on the basis of gender. Finally, the Indian Citizenship Act (Snyder Act) granted citizenship to Indigenous people of the U.S. in 1924.

True equality along racial and gender lines remains elusive, prompting additional federal legislative measures like the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, these three separate acts of legislation ensured, at least, basic recognition to various groups as U.S. citizens, guaranteeing them the same legal rights, such as voting.

In this sense, the Declaration of Independence was flawed, even as it spelled out the right to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” However, this document played a significant role in establishing such values we still possess as an essential part of being American.

An additional passage from the Declaration of Independence reads, “when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.”

Thus, Americans could alter the nature of governance; another significant contribution of the Declaration. It set the stage for future laws to safeguard citizenship to all groups and promoted a more modern reinterpretation of the phrase “all men are created equal” to mean “all people are created equal,” regardless of race or gender.

Kevin Kipers is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of History at Washington State University in Pullman.

This article is part of a Spokesman-Review partnership with the Thomas S. Foley Institute for Public Policy & Public Service at Washington State University.