Without Expo ’74, what might Spokane’s downtown have looked like?

To hear planning officials in Spokane in the early 1970s talk about it, the erasure of industry above the river falls downtown was an inevitability.

“The temper of the American public, once mostly concerned with economic development of the land, water and air, has turned now to include a concern for cleanliness, beauty and aesthetic values,” reads a 1974 report from the city’s Plan Commission for redevelopment of the riverfront area, a publication that predated the opening of Expo ’74 by just three days. “So it is with the people of Spokane.”

Yet much of the current talk surrounding the upcoming golden anniversary of the world’s fair, and past commemorations of downtown’s transformation, cast the herculean effort to host the event as the only thing that could have swept away the rail yards.

“If it weren’t for (Expo ’74), we might still have railroads downtown,” Spokane Park Board President Jennifer Ogden said at a meeting earlier this month.

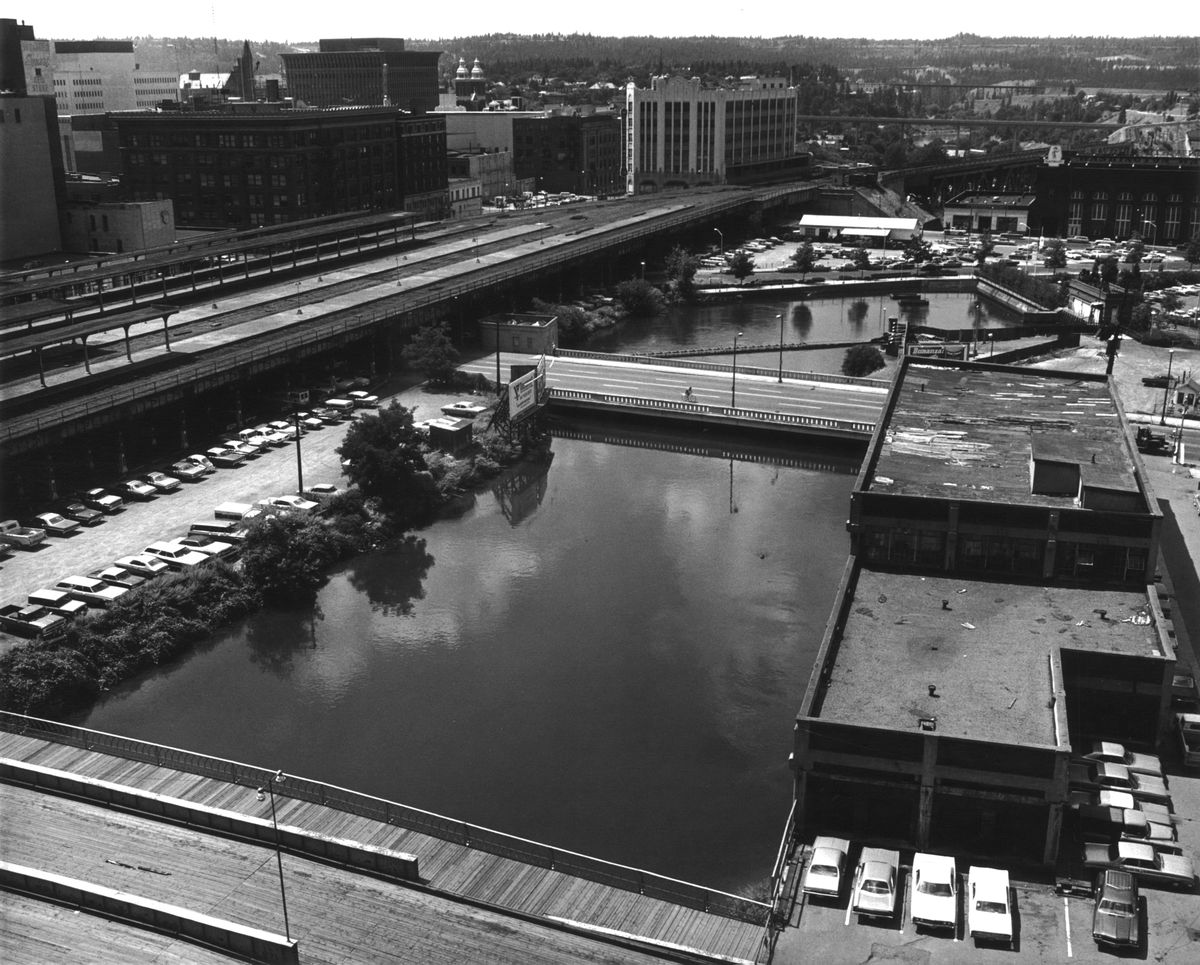

Two depots still stood downtown in the early 1970s, along with a tangle of elevated tracks and trestles that carried the cars of four railroad operators through downtown, over Havermale Island and along the banks of the Spokane River.

While it’s true that the combination of local, state and federal officials getting behind the Expo effort – including powerful U.S. Sen. Warren Magnuson and U.S. Rep. Tom Foley pushing for funds and the cooperation of the railroads – Spokane’s pitch for an urban exposition area and subsequent park was part of a deindustrialization push in downtowns that has continued to today, said Matthew Anderson, director of the Urban and Regional Planning Program at Eastern Washington University.

Spokane’s claim to fame may not be that it cleared downtown, Anderson said, but that it did it before other similarly sized cities.

“I don’t know of any other instance like this hitting a smaller, medium-sized city in the United States at that time,” he said. “Spokane is noticeable in having this happen early.”

At the time, Baltimore had launched its waterfront revitalization program to turn its aging ports into a tourist destination. Closer to home, Seattle was plotting ways to revamp its shipping areas on the Puget Sound, with Waterfront Park’s dedication in October 1974.

Beautification was a goal of the Expo planners, just as it was in those other cities, said David Evans, an architect who worked on plans for what would become the Riverfront Park grounds.

“It was also an opportunity to open the river up to the city,” he said. “To get the railroad structure out of there.”

Pressure for a downtown park also came from the seminal parks report issued by the Olmstead Brothers in 1913, calling for a park in the center of the city that would “preserve what beauty and grandeur remains of its great river gorge.”

There have been other pressures besides aesthetics that have prompted the decades of urban renewal that have followed, Anderson said. He pointed to what’s known as the “rent-gap theory,” an idea popularized by the Scottish geographer Neil Smith in the late 1970s. The theory holds that land that is producing less rental income than what could be achieved will attract private development, a phenomenon that would have likely occurred downtown even without a world’s fair.

Anderson pointed to subsequent developments after Expo, including the renovation of River Park Square (by the Cowles Co., publishers of The Spokesman-Review) and the building of Kendall Yards on the north bank of the river, as evidence there would have been investor interest in what became the 100-acre urban park.

“It’s hard to say that none of that would have happened without the Expo,” Anderson said. “I’m willing to bet that something else would have happened.”

Urban reclamation of former rail yards has followed the same trend as the waterways of Seattle and Baltimore. Albuquerque, New Mexico, is in the midst of redeveloping 27 acres of a former downtown railyard to include housing and commercial development. Sacramento hopes to revamp 244 acres of its downtown rail yard, the previous site of the western terminus of the First Transcontinental Railroad.

In other words, the continued existence of the old rail yards in Spokane, without Expo, seems unlikely. But Anderson noted that each city is different, and any idea about what might have sprouted downtown had boosters not insisted on a world’s fair devoted to environmentalism would be speculation.

“I’d say if you were to bet that it would have ended up a park anyway, I wouldn’t disagree with that,” he said. “History’s never preordained.”