‘How to Build a Human’ is an origin story that’s strange but true

Pamela S. Turner has written fascinating books about Japanese warriors (“Samurai Rising”) and astrobiology (“Life on Earth – and Beyond”), but her central subject has been animals – including dolphins, crows, frogs and gorillas – and the scientists who study them.

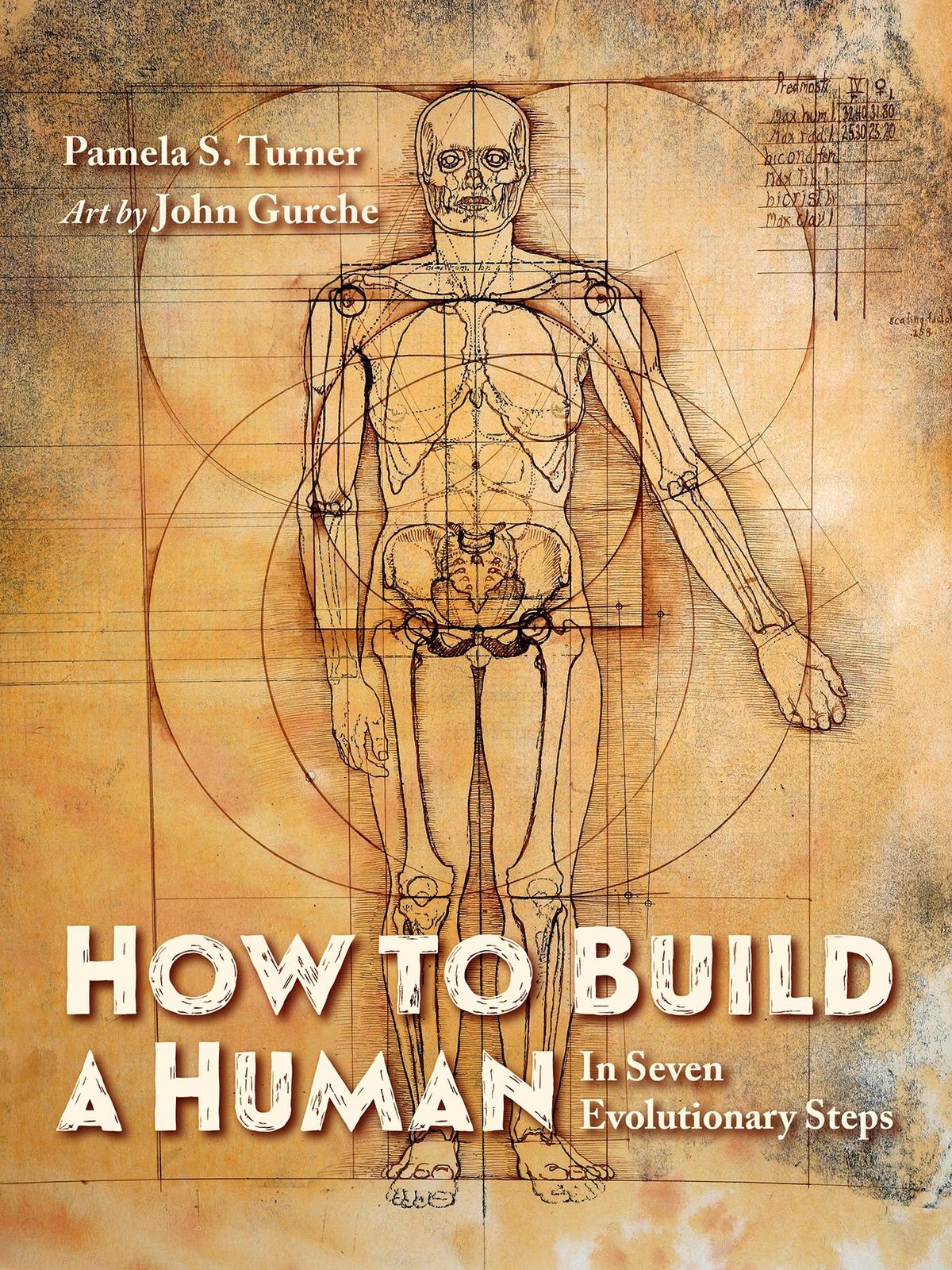

With “How to Build a Human: In Seven Evolutionary Steps,” Turner focuses on the human animal – and what she calls our “remarkably strange” origin story.

“First of all, we walk upright on two legs, the only mammal who does that, so we’re kind of bizarre out of the gate,” she said. “And then there’s our combination of high intelligence and abilities to cooperate. There’s no other mammal that cooperates with such intensity.”

Turner’s book describes the key milestones that our prehuman ancestors achieved on the way to becoming Homo sapiens. The liveliness of her account is previewed by her chapter titles: 1. “We Stand Up.” 2. “We Smash Rocks.” 3. “We Get Swelled Heads.” 4. “We Take a Hike.” 5. “We Invent Barbecue.” 6. “We Start Talking (And Never Shut Up).” and 7. “We Become Storytellers.”

Throughout the book, Turner uses humor and references to things such as video games and the Lord of the Rings fantasy series to help explain what she calls “a very heavy topic.”

“Our ancestors struggled to survive and often got weeded out by disasters, disease, accidents and predators,” she said.

For example, Nariokotome Boy, a Homo erectus discovered in 1984, apparently died young as a result of a gum infection.

These life-or-death struggles occurred in East Africa, where a huge rainforest gradually turned into a mixed habitat of woodlands, lakes, swamps, grasslands and other areas. Turner’s book shows how the challenges of environment, climate swings, predators and food extraction helped drive our evolution.

“I have a lot of respect for our ancient ancestors,” she said. “You would not want to walk across the Serengeti, among all these bigger, fiercer animals, with just a stone in your hand, and yet our ancestors managed to survive there and in many other environments.”

How scientists piece together human evolution through fossils is, Turner explains, “like trying to figure out a movie plot based on a few screenshots. … Every discovery, like that of Nariokotome Boy, adds another image that helps us understand how we changed, mentally and physically, over the past 5 to 7 million years.”

As with her previous books about animals, Turner writes in a way that encourages readers to understand the perspective of other species. From how she describes Lucy, a fossil that is about 3.2 million years old, you can imagine being an Australopith who used simple tools and perhaps climbed into a tree at night, with fellow Australopiths, for safety. About a million years after Lucy lived, you can see how important it was for Homo erectus to communicate and cooperate in hunting over large stretches of land.

Although we don’t know exactly when our ancestors figured out how to control fire, Turner helps you appreciate all the benefits of a campfire, including warmth, cooked food and peaceful conversation.

“There’s been a lot of appropriate and overdue appreciation of diversity,” Turner said. “I also think we should appreciate human universals – how we all came from the same place and have these common abilities that were carved into us through millions of years of evolution.”