Northwest Passages: DeFede got an unlikely start of stellar career in Spokane

Award-winning investigative reporter Jim DeFede owes his start in journalism to an unlikely series of events and his popular book about a small Canadian city’s reaction to the aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001, to an assignment that fell through.

For DeFede, who will appear at a Monday’s Northwest Passages event, the return to Spokane is a trip back to where his professional career began. He’ll be interviewed on stage by longtime friend and former fellow Spokesman-Review colleague Jess Walter.

“I think it’ll be fairly light,” he said in a telephone interview last week. “A couple of old guys, sitting on a stage, reminiscing.”

The event starts at 7 p.m. Monday at the Bing Crosby Theater.

Northwest Passages invited DeFede, now an investigative reporter for the CBS affiliate in Miami, back to his old stomping grounds to coincide with the Best of Broadway production of “Come From Away.” It’s a musical telling of how the people of Gander, Newfoundland, took care of thousands of passengers on trans-Atlantic flights that were ordered to land and stayed grounded there for days after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. He wrote a 2002 book about Gander’s response to those unplanned visits, “The Day the World Came to Town.”

But long before he was an acclaimed author or an Emmy-winning television reporter, DeFede was an intern at The Spokesman-Review. It was a job he almost didn’t get.

Born in Brooklyn, he attended Colorado State University, where he was student body president in his fourth year. He didn’t graduate but when he came back for a fifth year, the person who had covered him for the student paper became the paper’s managing editor and offered him the job of campus editor.

He hadn’t studied journalism in college, but enjoyed it so much that at the end of his fifth year – still without graduating – he decided journalism would be his career. He sent a résumé and samples of his writings to newspapers throughout the Northwest. And got back rejections.

“I got some mean rejections,” he recalled. When a large envelope from one paper arrived, he thought it might be a job offer and contract. Instead, the paper sent back his submission with a curt letter saying it didn’t accept unsolicited job inquiries. “Like it wasn’t even good enough for their garbage can.”

But he got an encouraging letter from Spokesman-Review Managing Editor Chris Peck. Still a rejection letter but one that complimented his submissions and wished the paper could offer him a job if it had an opening. It was the nicest rejection letter he’d ever seen – he would later learn it was a pretty standard letter from the editor – but he decided to call Peck and thank him.

He called the paper, was put through to Peck and they had a short and pleasant conversation that ended with “If you’re ever up this way, stop in and say ‘Hi.’”

DeFede bought a plane ticket to Spokane, called Peck back and said he’d just checked his schedule and just happened to be coming through Spokane in a few days. He flew up, paid for his own hotel room and came to the paper, where editors had just learned they’d received the money to pay for a three-month intern. He went through a series of interviews with a wide array of editors, went back to Colorado and waited.

“I got a call telling me I didn’t get the job,” he said. “That’s it, I figured.” He began considering a different career.

But when the candidate whom the newspaper hired showed up on her first day, she apparently became ill and fainted in the newsroom. The next morning she left a note with the security guard in the paper’s lobby that she wasn’t taking the job and left without ever returning to the newsroom.

That created a problem for the newspaper’s editors, who had to fill the position quickly or lose it. They huddled and one apparently said “How about that idiot who flew up here on his own? I bet he could get here fast.”

They called. He said he could get to Spokane right away and they offered him the job.

He threw everything he could fit and his dog into his car, left his other belongings behind and drove through the night, pulling off near State Line when he was too tired to continue.

The three-month internship became a six-month internship and eventually a one-year internship without an offer for a permanent position. At the time, other experienced reporters at the paper were trying to break a story on the “Shadle Park rapist,” who was suspected of having committed at least eight rapes, with victims ranging from a 5-year-old girl to an 60-year-old woman. A special police task force was trying to identify and catch the serial rapist.

Although not assigned to that story, DeFede did make “the rounds” at the police and sheriff’s offices every night as part of his beat. One night he picked up a tip that a man named George Grammer, who had been jailed for indecent exposure, might be the Shadle Park rapist.

DeFede went to the jail and asked to see Grammer, who came out to talk to him. Grammer denied being the rapist but said police had talked to him about it. After a brief conversation, DeFede asked if he could check in on Grammer, and when the inmate said yes, he visited frequently over the next several weeks on his own time, without telling the editors or other reporters.

“If I had said something (the story) would have been taken away from me because I’m just the intern,” he said.

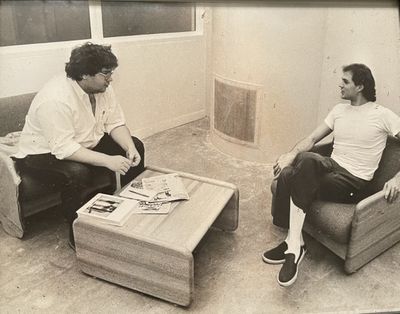

One Friday night on his rounds, DeFede saw Grammer was in one of the police interview rooms, eating a McDonald’s hamburger, a sign that he was cooperating with police. The next morning, DeFede went to see Grammer in jail, and the inmate confessed. He asked Grammer if he could bring in a newspaper photographer the next day so they wouldn’t have to use his booking photo.

“I told him ‘George you’re a good looking guy.’” Grammer agreed.

On Monday morning he walked into the newsroom and told the editors he had the story of the Shadle Park rapist, who was in jail. After they got over their shock and huddled for a conference, the editors told him to start writing.

Before he finished, however, the county attorney and some police officials came into the newsroom and asked to talk to the editors. There was another animated conversation in a conference room, and DeFede was eventually called in to learn that after some debate, the editors had agreed to hold the story to give police more time to build their case. But there was a condition that if a reporter from any other news organization called asking about Grammer, police would call the newspaper, which would run its story.

More than a week later, the newspaper got that call and ran the story. When editors got some criticism in journalism circles for sitting on the identity of a serial rapist, Peck deflected some of that by arguing that the real story was how the paper’s intern – who paid his own way to town to interview for the job, made about $250 a week and owned possibly one tie that no one had ever seen him wear – was so dogged that he developed a story on his own time that no one else had.

At that point, the editors figured they had to offer him a full-time job. He continued on the night police beat for a while, did a brief stint as the higher education reporter and later as court reporter. He covered the several big trials, including the trial of Alvin Hegge, Ghost Riders motorcycle club president convicted in the murder of police detective Brian Orchard.

“Alvin Hegge used to write me poetry,” DeFede said. “He wrote me from prison for years.”

The Spokesman-Review newsroom was where he learned the craft of journalism, DeFede said. Listening to investigative reporter Bill Morlin interview sources was “a revelation,” and he watched how Karen Dorn Steele, one of the nation’s top journalists on nuclear issues, methodically put together complicated stories. He also learned what mistakes to avoid by drinking with the staff of the copy desk after the paper went to press late at night. They were the final gate through which all stories passed, and over beers “they would rip apart every reporter and story.”

He also made lifelong friends with two other young reporters, Jess Walter and Anne Windishar, who later married. He became the central figure in several newsroom legends surrounding the newsroom’s annual Wet Dog Fur golf tournament and once played Santa Claus at a late December birthday party for a co-worker’s young daughter.

He left Spokane for the alternative weekly the New Times of Miami in 1991, where he worked for 11 years, spent three years as a columnist at the Miami Herald and now works as the investigative reporter at CBS4 in Miami, where he’s won several Emmys. He’s featured on a Netflix documentary “Cocaine Cowboys: Kings of Miami” about a pair of major drug dealers he wrote about while at the New Times.

In late 2001 he got a call from Judith Regan, a New York publisher looking for a ghost writer for one of the New York City officials who responded to the terrorist attacks and their aftermath. Walter, who works with Regan on many of his books, wasn’t available and suggested DeFede for the job.

That project fell through, but Regan had read a short article about the planes that had been forced to land and remain in Gander after the Twin Towers came down, and the way the residents took care of the unexpected influx of temporary residents. She thought it would make a good book although her editors thought it was, at best, a magazine article.

Sensing an opportunity, DeFede said “I absolutely agree with you.” He flew to Gander in February 2002, spent two months there interviewing residents, then returned to Miami and contacted passengers who were now scattered around the world. The book, “The Day the World Came to Town,” won a Christopher Award in 2003, presented to books that “signal individual worth and the power to positively shape the world.”

The events in Gander are the basis for “Come From Away,” and many of the characters are in the book. But the writers never contacted him and no one from the musical has ever acknowledged a connection, although he was told by actors in one production they were given the book to prepare for their parts.

The characters are real people and “I don’t own the rights to their life stories,” DeFede said.

“Come From Away,” has toured in the United States, Canada, Ireland and London, and is currently one of the longest running productions on Broadway. DeFede said he was a little surprised when he first heard the story was being made into a musical.

“When you think 9/11, you don’t automatically think musical,” he said.