Oakland woman claims New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art secretly sold her grandma’s Nazi-stolen van Gogh

SAN JOSE, Calif. – An Oakland woman last week sued the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, claiming it bought then secretly sold a Vincent van Gogh painting the Nazis stole from her grandmother.

The lawsuit was filed in federal court by Oakland’s Judith Silver, her sister Deborah Silver, and seven others from Los Angeles, Seattle and Israel named in the suit as surviving heirs of the painting’s purported owner Hedwig Stern, who ended up in Berkeley and then Southern California after fleeing Germany in 1936 to escape persecution of Jews that culminated in the Holocaust.

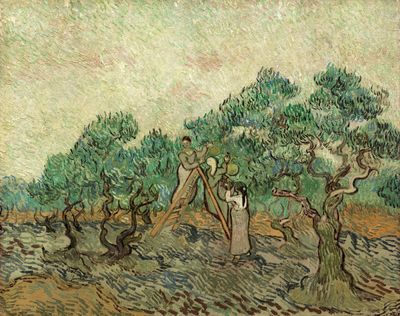

Silver, who is in her late 50s, and her co-plaintiffs describe a shadowed path taken by van Gogh’s 1889 “Olive Picking,” from its theft by the Third Reich to its sale to a renowned museum to its disappearance for decades and re-appearance in a Greek gallery as recently as this month. They allege the Metropolitan Museum’s former prominent expert in Nazi art looting knew the painting by the Dutch post-Impressionist had been stolen by Adolf Hitler’s genocidal dictatorship, and approved its purchase and later, its secret sale to a Greek shipping tycoon who hid it for years. A history compiled by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum from Stern’s family papers fills in details of her escape from the Nazis, her arrival in Berkeley via New York, and the birth of her granddaughter Judith in 1963.

The Metropolitan Museum did not respond to a request for comment. In September, the museum said it had identified 53 works in its collections seized or sold under duress during the Third Reich, but that it had obtained all of them after return to their rightful owners, the Associated Press reported. History professor Jonathan Petropoulos of Claremont McKenna College in Southern California told a Congressional committee in 2000 that the Nazis stole 600,000 artworks from Jews in Europe and the former Soviet Union between 1933 and 1945.

According to the suit filed Thursday in U.S District Court in San Francisco, before Stern fled Munich, the Gestapo secret police stopped her from exporting the van Gogh, which depicts a bucolic orchard scene rendered with the artist’s typical strokes in thick paint on a 29-inch-by-36-inch canvas.

Stern, born in 1898 and the daughter of a textile and fashion company owner, first tried to escape Germany in November 1936 with her husband Fritz, but the night before their planned departure from Munich, two policemen confiscated Fritz’s passport, the Holocaust Memorial Museum’s history said.

Two days later he received it back and the couple traveled to Hamburg, a large port city in the north of the country, “but prior Fritz was warned by his attorney that if they boarded the ship they would have been arrested,” according to the memorial museum’s history. The Sterns finally escaped Germany in December, and arrived in New York in early January 1937, then went on to Berkeley, where they had friends, before moving to Pasadena six months later. Stern died in 1983, long after the passing of Fritz in 1955. Stern had searched for the painting for years, but never found it, despite “serious and diligent efforts,” according to a report on the painting and its fate by Petropoulos submitted as an exhibit in the lawsuit.

The Nazis looted at least five of Stern’s paintings, including a Renoir, but she was able to recover only two, and was compensated for the loss of an additional one through a 1958 ruling by the German government, the report said.

The Sterns’ daughter Eva, who died in 2009, is the mother of plaintiff Judith Silver, who was born in 1963, and her older sister and co-plaintiff Deborah Silver of Los Angeles, born in 1961.

The lawsuit alleged that back in Germany a year-and-a-half after the Sterns’ December 1936 escape, a Nazi-appointed trustee sold the van Gogh to a German collector, and the Gestapo seized the proceeds.

The Silver sisters and the other stated Stern heirs believe the painting was transported to Paris in early 1948, than transported to New York by a German art dealer on behalf of the collector, and sold before the year was out to Vincent Astor, a Harvard College dropout who had inherited a fortune from his father John, said to be the wealthiest passenger to die in the sinking of the Titanic. Astor allegedly sold the painting to the Metropolitan Museum in 1956 for an amount unknown to the Stern heirs.

Stern’s efforts to find her van Gogh included traveling in 1951 to Germany seeking to get it back or obtain compensation, but the German government declined to compensate her, saying the painting had never become the property of the Third Reich, according to the report by Petropoulos, a frequent expert witness for Holocaust victims taking legal action to recover Nazi-stolen art.

Petropoulos said in his report he believed the Metropolitan Museum could have tracked true ownership of the painting back to Stern. The suit claimed that the museum’s chief curator at the time, Theodore Rousseau, “knew or consciously disregarded that the painting had been looted from Hedwig Stern by the Nazis” but still approved its purchase and secretive sale.

Rousseau had deep-rooted expertise in Nazi art theft, according to Petropoulos’ report. During the Second World War, Rousseau was an officer in the CIA’s predecessor agency the Office of Strategic Services, working in the Art Looting Investigation Unit – a sister agency to the Allies’ Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program central to the 2014 film “The Monuments Men,” starring George Clooney, Matt Damon and Bill Murray.

Rousseau was also a wartime colleague of Lane Faison, one of the U.S. Army’s “monuments men” from the Allied program, and the two remained friends until Rousseau’s 1973 death, according to Petropoulos’ report. Stern in 1951 had met with Faison, who had stayed with the monuments program after the war, and reported the loss of her van Gogh. Faison could have told Rousseau who owned “Olive Picking,” Petropoulos claimed in his report.

Still, the Metropolitan Museum in 1956 sold the van Gogh to Greek shipping magnate Basil Goulandris in a transaction that Petropoulos described as “shrouded in mystery.” Petropoulos alleged in his report that it is “reasonable to conclude” that the Metropolitan Museum sold the painting secretly to avoid having to return it to Stern.

The Greek tycoon and his wife, Elise, the suit claimed, hid “Olive Picking” “for decades.” The Stern heirs had no concrete information about the painting’s location until 2003, when a report from a Berlin law firm specializing in unsettled property issues indicated it was probably in the Goulandrises collection, according to Petropoulos’ report.

The Greek couple are dead, but the painting, completed in a mental asylum less than eight months before van Gogh took his own life, was put on display earlier this year at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and as recently as Dec. 10 in the Athens museum of a foundation the Goulandrises set up, the suit alleged. The museum reportedly houses billions of dollars in art, Petropoulos’s report said.

In the lawsuit, Silver and the other Stern heirs are seeking return of the painting from the foundation, restitution from the Metropolitan Museum equivalent to the amount it allegedly received by selling the van Gogh, and unspecified damages. Paintings by van Gogh typically sell for millions to tens of millions of dollars.

The museum has said it has provided restitution or reached settlements in the cases of eight Nazi-looted works, including a painting by Claude Monet.