‘Mr. Business, that’s what he was’: Young Cooper Kupp didn’t take Yakima by storm, but his perseverance was legendary

YAKIMA – As patrons sipped on beers at the Second Street Grill on a recent weekday afternoon, football action flashed on the big screens that hung on every wall.

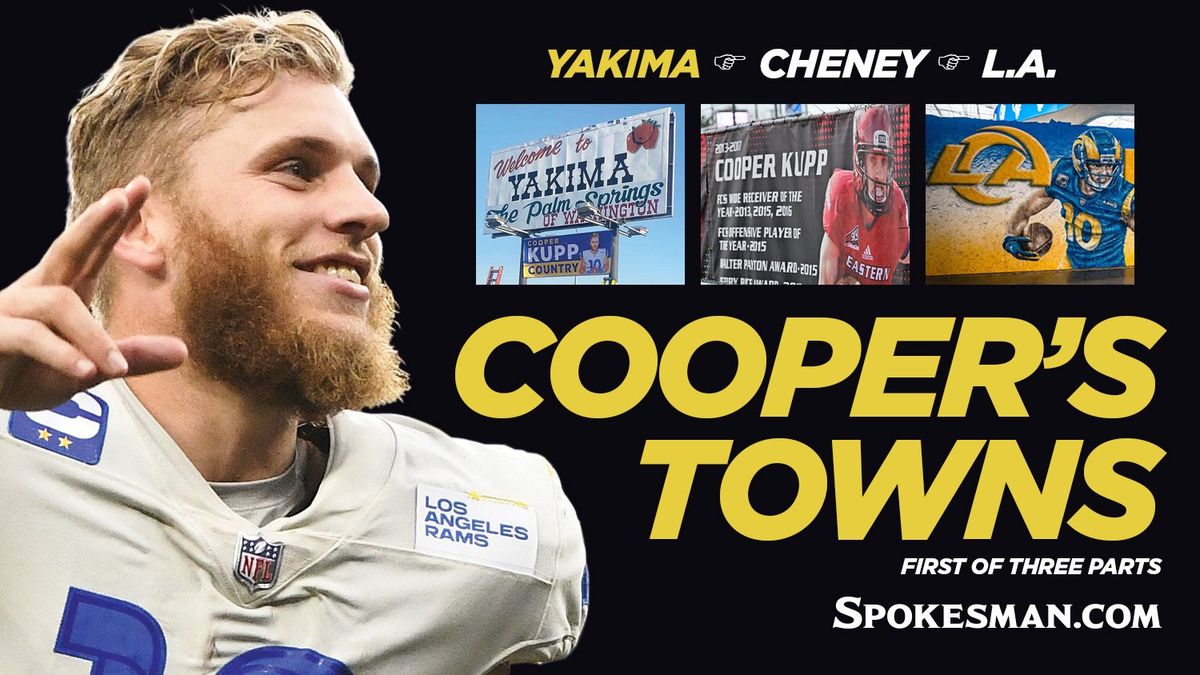

The show was a preview of the upcoming Super Bowl between the Cincinnati Bengals and the Los Angeles Rams, and the dominant figure was Cooper Kupp, a wide receiver for the Rams and the biggest sports hero Yakima has seen in decades.

There was Kupp, running downfield and catching the pass that ushered Tom Brady into retirement. Another clip showed the catch that sent the Rams to the Super Bowl.

His statistics flashed on the screen: crazy numbers, the best in the NFL for catches, yards and touchdowns, a triple crown not seen since 2004.

The sportscaster gushed: “What a season it’s been for Cooper Kupp.”

If only Kupp played for the Seattle Seahawks.

“We hear that over and over again,” said Kupp’s grandfather Jake Kupp.

“This is strictly a Seahawks town,” he added. “Everybody tells us, ‘I’m pulling for Coop and hope that he catches a bunch of touchdown passes, but I hope the Seahawks win.’ ”

But Yakima is proud of its latest favorite son and, on Sunday, many will gather at “Cooper Bowl” parties and root for Kupp.

Signs have popped up throughout the Yakima Valley, the most prominent being a poster of Kupp under a truck-mounted sign proclaiming Yakima as the “Palm Springs of Washington.”

“It’s just so cool having a guy like that from Yakima and from Davis,” said Peter Schilperoot, a server at the Second Street Grill.

Despite his pedigree – his father and grandfather also played in the NFL – Kupp’s trip to Sunday’s big game has the makings of an underdog story.

His successes and failures are in many ways tied to A.C. Davis High School, a lower-tier college football program at Eastern Washington and an NFL franchise that’s trying to find its place in the sporting hierarchy of greater Los Angeles.

All are better from their association with Kupp, the hard-working kid who has overachieved at every stop and now stands one game from the summit.

And who couldn’t cheer for that?

Of genes and dreams

As Jake and Carla Kupp descend into the basement of their home in west Yakima, he offers an apology.

“I suppose you could call it a man cave, but not much of one,” Jake says.

That sells it short by a mile. On the walls are photos and drawings from his own playing days at the University of Washington and 12 seasons as an offensive lineman in the NFL.

Most of them were spent with the New Orleans Saints, where he was All-Pro. A trophy marks Kupp’s enshrinement into the Saints Hall of Fame.

“But here’s the one I’m most proud of,” the elder Kupp says as he points to a photo from a 2018 game between the Saints and the Rams, when he and his grandson met for the coin flip.

Jake Kupp is also proud of his grandson’s combination of confidence and humility.

“In his mind, when he steps on the field, he knows that he’s the best player on the field, but he keeps that to himself, so it’s not something that he can take credit for. He gives credit to God.”

Cooper Kupp’s success is built on hard work and a superlative gene pool, facts chronicled by writers from the Los Angeles Times, Sports Illustrated and others.

It’s also built on a foundation of family and faith, and nurtured by dreams.

Jake Kupp spoke of his own father back on the farm in nearby Selah and a work ethic that filled the days with labor and the evenings with hikes in the hills.

The dream was passed down to his son Craig – Cooper’s father – who played quarterback in the NFL for two seasons. For years, the father threw balls to an eager son with a knack for catching passes.

“I’m just so proud of what he’s been able to accomplish,” Craig said.

“I was so lucky,” Cooper Kupp recalled. “I had an NFL quarterback as my wide receiver coach growing up. If I didn’t run a double-move right, my dad would let me know about it.”

They allowed young Cooper to chase those dreams. Youth baseball saw him through the hot Yakima summers.

And then he found a new field of dreams.

“I was 9 years old and a football team was practicing in the outfield,” Kupp once said, “so I went over and checked it out.”

A class like no other

Kupp may never be the most famous alumnus of A.C. Davis High School.

That honor belongs to William O. Douglas. Growing up in desperate poverty, he went on to serve a record 36 years as a justice on the United States Supreme Court.

A statue of Douglas sits in a courtyard at Davis.

As the city grew, new high schools – Eisenhower and West Valley – were built in the more affluent west side. Davis has been an underdog ever since.

“They say there’s not a big divide, but there’s very much a difference,” said Jay Dumas, formerly the offensive coordinator at Davis and now the head coach.

“We’re the downtown school and in the ’hood,” Dumas said.

The Kupps lived on the west side, where Cooper attended Wilson Middle School and seemed destined to attend Eisenhower. But Davis had introduced an International Baccalaureate program, which attracted Kupp.

The bigger draw was the camaraderie he’d found in the Grid Kids program. Teammates David Trimble and Deion Wright were the stars.

“But I kept hearing about this other kid,” Dumas said. “He was different from everybody else in what he was trying to get out of the game, super smart.”

But would Kupp burn out by the time he reached Davis? “You just never know,” Dumas said.

Finally, the parents took what Dumas called “a bold move” and sent their sons across town.

No one knew it yet, but Kupp and his classmates would transform the collective mindset at Davis.

“They changed the whole dynamic, the whole attitude,” basketball coach Eli Juarez said. “They said ‘we’re going to get to class, we’re going to work hard.’”

Building a new tradition

In the football office, Dumas points to a picture of the freshman football squad of 2008.

“Can you pick out the future All-American wide receiver?” he asks.

It’s a rhetorical question, answered by picking the most unlikely candidate out of about 40 kids. Most are in full pads.

And there he is: the skinny blond kid, clad in street clothes and his left shoulder in a sling.

Kupp was 5-foot-5 and 115 pounds when he arrived at Davis, and physical growth came only gradually.

But in the meantime, he sneaked into the weight room during off hours and trained, “even when the results weren’t necessarily showing up,” Dumas said.

“The others kids would lift weights and then look in the mirror to look buff, but he was more mature about the process,” Dumas said.

“Mr. Business, that’s what he was,” Juarez said.

During road trips in basketball and football, the coaches recall that Kupp would always pass on the Whoppers and the Quarter Pounders – “though he might have grabbed a few fries,” Dumas said.

There was some kidding on the bus, “But for Cooper it was more of a term of endearment,” Dumas said.

And while his teammates weren’t going that far in the pursuit of healthy living, Kupp’s work ethic rubbed off.

“We were playing Wenatchee and we were very young,” said former head coach Rick Clark.

“Coop dropped two balls in the end zone and took it really hard, and after that he wouldn’t leave practice until he caught about 100 balls,” Clark said.

However, to this day Kupp said he’s “grateful” – one of his favorite words – for the “next-level” coaching from Dumas and others. During a virtual interview Super Bowl week, Kupp also acknowledged the sacrifices of his parents – “me not having to work summer jobs, allowing me to work out and get better.”

Outside observers had the same takeaway.

“He was the hardest worker, but he was smart, like another coach on the field, and always seemed to be in the right place at the right time,” said Scott Spruill, a longtime sportswriter at the Yakima Herald newspaper.

“And everything that you see in the media about how he’s perceived with the Rams is exactly how he came across here,” Spruill said.

The Pirates reached the postseason in 2011, Kupp’s senior year, losing to Mead in a playoff game at Albi Stadium.

Basketball season followed immediately. Some of the players had been together since fifth grade, and it showed.

Kupp wasn’t the leading scorer, but did all the little things – “that great screen, that critical basket,” Juarez said. “Always at the right place at the right time.”

By the end of the year, the Pirates were state champs. A team portrait hangs at the entrance to the gym, which was rebuilt after Kupp graduated. A few feet away is a collection of photos showing Kupp in the uniforms of Davis, EWU and the Rams – an inspiration to others.

Dumas gazes at the display.

“He rubbed off on people here the way he did at Eastern,” he said. “And now he’s doing it on the biggest stage in the world. We couldn’t be more proud.”

And who wouldn’t cheer for that?

Jim Allen can be reached at (509) 459-5437 or by email at jima@spokesman.com.