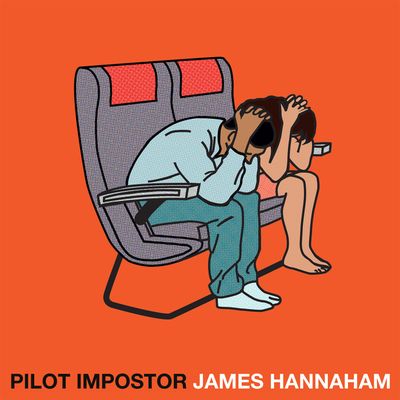

Book review: ‘Pilot Impostor’ proves that James Hannaham is one of America’s most inventive writers

James Hannaham’s first two novels, 2009’s “God Says No” and the PEN/Faulkner Award-winning “Delicious Foods” of 2015, vaulted him to the top tier of inventive American writers. Now, the publication of “Pilot Impostor” should secure his place at the apex. Hannaham is not only creative or stunningly gifted or intellectual or supremely original, but he also is all those distinctions at once. This genre-defying book of compressed prose, poetry and image is the product of a mind – and heart – pushing the artistic tachometer to the red line.

Its genesis was a flight to Lisbon just after the 2016 election. Hannaham was reading Fernando Pessoa, the great modernist who inhabited a multiplicity of voices he called heteronyms – some 70-plus personae that were simultaneously aspects of himself and whole-cloth creations. This protean assembly provides Hannaham the ideal entry to an exploration of self, consciousness and creativity.

“Pilot Impostor” is the record of a Black man observing himself observe a deeply peculiar moment. The controls of the American experiment were newly in the hands of a man embodying the “poison cocktail of faked experience plus confidence,” as Hannaham described in an essay in Bookforum. The role of algorithms in determining what we perceive was increasingly insidious. And he was on his way to a country that had birthed both the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the odd genius of Pessoa.

The book delves into these themes, and many more, all interlocking by way of Hannaham’s visual art and brief textual performances, stills from air disaster videos, screenshots and fragments of Pessoa’s work. The book is so thoroughly fused it is difficult to extricate an example, but I was particularly struck by a list piece titled “To Confound Forensics.” This surreal compilation of ways to get away with murder (No. 16: “Be a chimera.”) is juxtaposed on the facing page with a screenshot showing a Facebook pop-up that warns “You are viewing your profile as someone else.”

Hannaham suggests each of us now encompasses such a multitude of heteronyms, to feed algorithms that then feed us, it can make a Pessoa of anyone. What is the self, and how can we know it? The role of chance in determining experience is perhaps the overriding, but far from only, subject of this ingeniously faceted book. It returns again and again to the strange fact that much of life is now conducted inside a box outside ourselves to which we outsource our thinking. The computer looks at things for us, through the remove of the camera eye; it remembers things we will forget; with its help, we make “profiles,” or alternate selves.

The idea that consciousness is but a contingent arrangement of experiential fragments is reflected in both the structure and content of the book. Hannaham’s short texts – philosophical inquiries, experimental and speculative fictions, prose and poems, even a Bowlesian Sonnet – each respond to a brief bit of Pessoa’s poetry hovering suggestively in the margins of the page. These in turn respond to each other, while the author’s subtle ordering poses a question about whether it is possible to ever know the “real” Pessoa. (Answer: Is there a real anyone?)

“Pilot Impostor” has as many fine gears as a Swiss watch. Its several organizational principles together imply the creation of self only unfolds over time – we become most “ourselves” as we accumulate the sediment of what by chance happens to us. Some of these are accidents. Some are delivered in our DNA. But we make something of them nonetheless – a narrative informed by cognitive bias, a fictional projection, a work of art. Or a book that accomplishes them all.

The visuals here are in conversation with the texts, which are themselves in conversation with the fragments from Pessoa. Images from air disaster videos, as well as hoax imagery that proliferates online – such as the meme known as “9/11 Tourist Guy” that purported to show a man on the deck of the World Trade Center moments before a plane hit – comment on the ways digital obsessions take shape.

Other images include Hannaham’s assemblages of thumbnail photos of surfaces (Portuguese tile, stained glass and mosaics) and apertures (sky, grates and perforations), still bearing their digital sizing tools. With them, the artist proposes that factuality is contextual and perception nothing but an artifice of composition.

Hannaham’s signature sly humor often carries a surprise hit of acid. His first novel is a comic but compassionate exploration of race, sexuality and religious hypocrisy that tempers its outrage with absurdism. His second posits the plantation slavery system’s persistence in contemporary society; where there were chains and whips, there is now drug addiction, to the same end. Famously, one of “Delicious Foods’” central characters, with its own idiosyncratic voice, is crack cocaine. Ventriloquism is only one of Hannaham’s profuse talents.

Melissa Holbrook Pierson is a critic and the author of “The Place You Love Is Gone,” among other books.