‘He became a hero’: Remains of Gonzaga alum, U.S. Navy pilot shot down in Vietnam return home after decades of uncertainty

Dona Re’ Shute and Lorraine Charvet didn’t realize their family needed closure until they got the call.

It was from the Navy, who called Charvet this past May – two weeks before Memorial Day. The Navy told her that the remains of their brother, U.S. Naval Reserve Cmdr. Paul Charvet, would finally return home after more than 50 years across the Pacific.

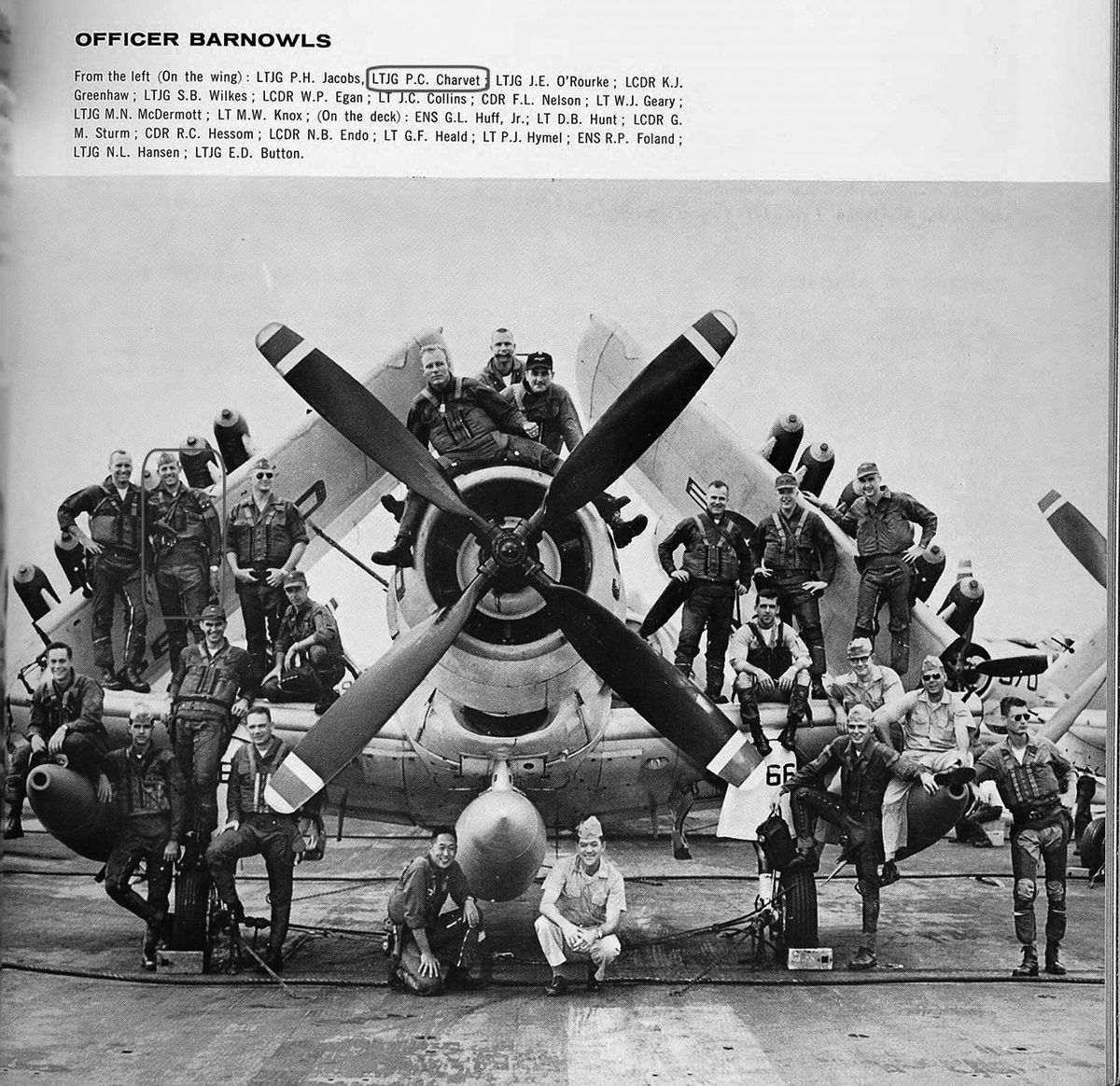

A graduate of Gonzaga University, Paul Charvet flew a single-seat A-1H Skyraider in the Vietnam War. Taking part in a three-plane flight supporting a naval gunfire mission on March 21, 1967, the 26-year-old’s plane was apparently shot down northeast of Hon Me Island near Thanh Hoa Province, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

Shute said the mission took place on the last day of his third and final tour, as he planned to retire and return home.

Instead, he was declared missing in action for more than a decade until December 1977, when the military updated his status to “Presumed Killed in Action,” according to federal records.

“We had a funeral service for him in Grandview, Washington, where we grew up, and that was that,” Shute said. “That was our closure, as much as we could have and figured we’d ever have.”

Shute and Charvet said the Navy kept in touch with the family in the years that followed.

Radio Hanoi reported the day after Paul Charvet’s mission that an American aircraft was shot down the day before. His plane was the only U.S. aircraft lost in that area that March 21, federal records show.

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam on Sept. 24, 2020, turned over presumed human remains and material evidence to the United States, along with additional evidence that October.

The remains were sent to a laboratory at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam for identification, which was finalized in May 2021.

The recovery of Charvet’s remains was recognized by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin in September during a POW/MIA Recognition Day ceremony. At that time, Austin said the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency had accounted for 135 missing soldiers last year to date, including one from the Vietnam War.

“In a sense, that’s what we still seek: Answers to simple questions,” Austin said. “Where are they? And when can they come home?”

Charvet’s family gathered Wednesday in Anchorage, Alaska, for a Navy ceremony commemorating the return of his remains.

His mother, Blanche Charvet, 101, lives in Anchorage with Lorraine and a granddaughter. His father, Ray Charvet, flew coastal air patrols during World War II.

“I think mom understood that Paul was coming home,” Lorraine Charvet said. “I think she said something like, ‘that’s good. That’s wonderful news.’ ”

Shute said the family plans to have him eventually buried in Mabton, Washington, alongside his father.

“We really didn’t think that we needed any more closure, but this really does close it out in a beautiful way. A peaceful way,” Shute said. “It’s certainly given me a lot of comfort.”

Locally, Gonzaga University placed a wreath Wednesday at a commemorative plaque at what’s known as “The Freedom Tree” outside of the Crosby Center.

The tree was dedicated in 1975 out of an idea that originated from members of Paul Charvet’s Class of 1962, according to the university. The tree was inscribed with a plaque in commemoration of Charvet and all prisoners of war, as well as those missing in action.

Charvet, an English major who played on the varsity baseball team, married another Gonzaga alumna, Christina Johnson.

For Kara Hertz, executive director of Gonzaga’s alumni relations, getting the call from Charvet’s family that his remains were coming home was also “one I won’t forget.”

“Hearing the reflections and looking at his pictures in the yearbook, you can just picture him as a student on our campus,” Hertz said. “He was clearly very talented, and went on to offer these talents in generous service to our country.

“He became a hero, paying the ultimate sacrifice,” she continued. “What a remarkable man.”