This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

100 years ago in Spokane: The growing railway strike showed subtle signs of success

Events were moving rapidly in one of the largest strikes in Spokane history, in which 1,800 railroad shop workers had walked off the job.

First, tensions cooled slightly when union leaders agreed to abide by a no-picketing order from a federal judge. They agreed to refrain from even “loitering or congregating” near railroad property, so as not to intimidate the nonunion workers.

Why did they agree not to picket?

Union leaders clearly wanted to show that they were law-abiding. Yet there might have been another reason for their willingness to cooperate: They were winning on another, more important, front.

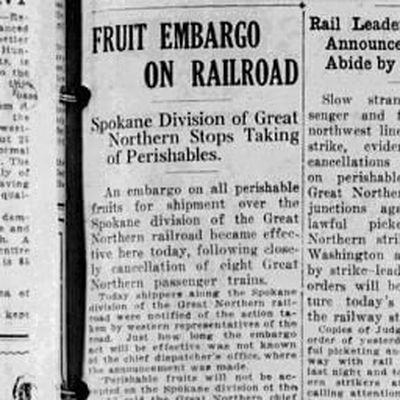

They were succeeding in forcing a “slow strangulation of passenger and freight traffic,” in the words of the Spokane Daily Chronicle. The railroads, short of manpower, announced more route cancellations and an embargo on carrying perishable goods.

The Great Northern discontinued eight passenger trains, including four on branch lines out of Spokane. Many freight lines were stalled or slowed due to congestion caused by rail cars in disrepair. The Northern Pacific had “annulled” 23 trains in the western division alone. The two other railroads serving Spokane, the Milwaukee Road and the Union Pacific, had not discontinued any routes yet, but “this may be necessary shortly.”

Other rail workers were now contemplating joining the strike, including clerks, freight handlers and station employees. Spokane had between 600 and 700 workers in these classes.

From the lavatory beat: The Davenport Hotel, already known for luxury, was planning something special for its women employees: A women’s restroom among “the most elaborate in the United States.”

This was no ordinary employee restroom. When completed, it would be more like a “club room,” with lockers, safes, showers, lavatories, lounges, easy chairs, tables, a library stocked with magazines and a coat room. It would even have a small “hospital” with eight cots under the supervision of a trained nurse.

The manager said they wanted a place where “our women help could rest between working hours.” Many of them worked a few hours in the morning and then a few hours at noon or in the evening. With this new “club room,” they could relax without going back and forth to home. The Davenport employed 250 women.