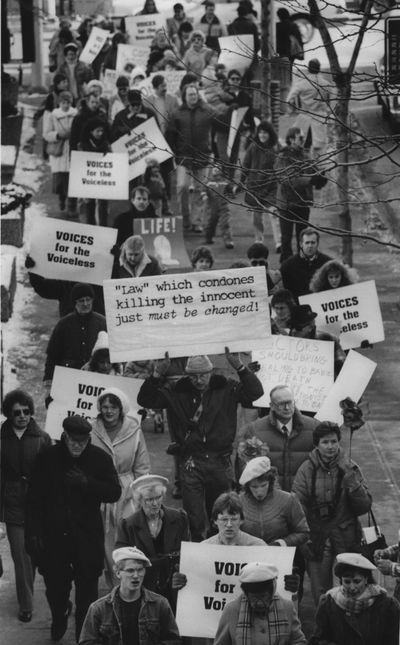

How Spokane became a national hotspot for anti-abortion protests in the mid-1980s

In a sense, Washington was an unlikely spot for a flashpoint over abortion.

But nearly a dozen years after the Roe v. Wade ruling was released, Spokane became a national hotspot for protesting the landmark decision that declared a woman had certain rights to choose whether to have an abortion without interference from government.

State voters had approved more limited abortion rights several years before Roe, and even most members of the state’s Republican congressional delegation supported those rights. But the presidential races of 1980 and 1984 energized Christian conservatives, drawing some into the state and local Republican organizations.

In late 1984, a small, loosely knit group called Share began demonstrating in front of the 6th Avenue Medical Building, approaching women they thought might be having an abortion and trying to talk them out of it. While the nine-story building did have several obstetric practices, it was home to a wide array of doctors and dentists, along with a first-floor pharmacy.

The weekly demonstrations, which participants called “counseling,” continued into the snowy winter of early 1985, when sidewalks were filled by demonstrators and patients entering the building couldn’t easily maneuver around them.

Drs. Stacie Bering and Pam Silverstein, who had an obstetrics and gynecology practice in the building, became concerned that their patients were being harassed. One of the doctors at another practice in the building did perform abortions. Bering and Silverstein did as well but only at Deaconess Medical Center a few blocks north. Some doctors who had other types of medical practices said their patients were being harassed by demonstrators who assumed they were there for an abortion.

The doctors talked with Bering’s attorney husband, Jeffry Finer, and the senior partner at his firm, Pat Stiley, about a possible legal remedy to protect their patients. Stiley had gained some fame earlier in Spokane as a protester to the Vietnam War and was familiar with First Amendment law – but on the other side of the argument.

Eventually, they filed a lawsuit in Spokane County Superior Court, seeking restrictions on where demonstrators could gather. Bering v. Share, as the case came to be known, was a political hot potato that landed on the desk of Willard Zellmer, a visiting judge from Lincoln County who regularly handled overflow cases in much busier Spokane County.

Zellmer issued a temporary order that protesters had to stay across the street from 6th Avenue, or on the sidewalk along Stevens Street. Some protesters followed the new rules, but others, especially Teresa Lindley and Grace Gerl, refused.

Russell Van Camp, an attorney who specialized in civil torts, agreed to represent the protesters pro bono, and a legal battle between constitutional rights of free speech and privacy ensued. The arguments centered in part around whether a right to an abortion, as spelled out in the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, was a piece of the constitutional right to privacy.

Lindley and Gerl refused to comply with Zellmer’s order as it went through several hearings. The judge repeatedly warned them he would jail them if they continued. On April 20, he did, telling the two women he’d release them if they promised to obey the order.

They spent 12 days in jail before agreeing to obey the order. They were released, posted bond and moved their protest to the sidewalks outside of Deaconess, while others protested at the 6th Avenue building, often in violation of the court order.

Meanwhile abortion foes from around the country, including Beverly LaHaye, the founder of Conservative Women for America, Joseph Scheidler, author of “99 Ways to Close an Abortion Clinic,” and Michael Farris, a Gonzaga Law School graduate and founder of the Home School Legal Defense Association, flocked to Spokane. They held a rally at the First Assembly of God Church on West Indiana Avenue and urged a crowd of about 400 to defy the injunction.

Some protesters, including a state legislator, were cited, fined and told they would be jailed if they violated the order again.

Zellmer’s injunction was appealed, and upheld first by the state Circuit Court of Appeals, and in June 1986 by the state Supreme Court in a landmark case that spelled out what sort of restrictions can be placed on demonstrations. It was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to take the case in 1987.

Lindley, Gerl and the Rev. Dan Scalf, who was active in the protests and repeatedly warned to obey the injunction, were eventually charged with criminal contempt for violating the order. After a trial in August 1986, Scalf was convicted, although Lindley and Gerl were acquitted.

The restrictions remained in place, and the 6th Avenue Medical Building remained a target for abortion foes. In early 1989, a U.S. District Court judge in Seattle put further restrictions on mass sit-ins by abortion opponents.

In March of that year, nearly four years to the day from the issuance of the first order from Zellmer, 101 protesters were arrested in an event planned by Northwest Rescue. They were charged with trespassing after entering the building when it first opened and occupying two floors, shutting operations down until mid-afternoon. Most were booked and released, but dozens refused to give their names and had to remain in jail over the weekend until they could be arraigned the following Monday.

By that time, the local chapter of the National Abortion Rights Action League had trained “escorts” to accompany patients arriving at the building for the procedure.

Then-Police Chief Terry Mangan criticized the protesters for clogging up the local jails, putting the public at risk and monopolizing police resources with their unannounced sit-in. An organizer for the protest countered that if they had announced the protest, women would have rescheduled their appointments.