We the People: How the myths of George Washington’s life hold up mirror to many today

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: George Washington is famous for many things. Name one.

In many ways, George Washington is more famous for things that he never did than his many real-life accomplishments. Despite leading an extraordinary life, the popular perception of Washington is shrouded in myth to a greater extent than any other founder. And we have been perpetuating myths about him almost from the moment he died on Dec. 14, 1799.

Washington’s first biographer, “Parson” Mason Locke Weems, created many of the popular myths that still envelope the “Father of Our Country” today. Published in 1800, Weems’s “The Life and Memorable Actions of George Washington” was a runaway hit that went through 20 editions over 25 years. The major theme running through Weems’s account of Washington’s life was the central importance of his Christian upbringing to his later greatness. Weems zeroed in on an almost entirely fictitious relationship between George and his father Augustine, most famously encapsulated in the myth of the cherry tree. Augustine’s nurturing of the young George through biblical teachings meant that his son had the moral courage to confess to his father that he had, indeed, felled Augustine’s favorite fruit tree with his new hatchet. He couldn’t “tell a lie.”

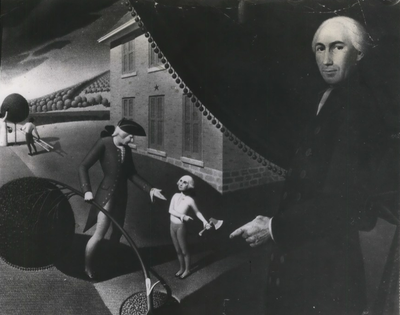

Washington’s religiosity didn’t end there. Weems, trained as an Episcopal priest, continued to weave a strong thread of Christian faith through George’s life. One of the most popular images of George Washington today is of the general deep in prayer on his knees in the snow at Valley Forge. Weems created the Valley Forge prayer myth in an 1804 article before including it in the updated 17th edition of his Washington biography that appeared in 1817.

And, of course, in his final moments on earth, Weems reported Washington’s piety on his deathbed as he prepared to meet his maker. A fitting end to a great life owed to Christian piety.

Professional historians have thoroughly debunked Weems’s highly fictionalized account of Washington’s life. While Washington was an Episcopal vestryman, there is no evidence that he espoused the deep religiosity assigned to him by Weems. In his myth-busting book, “Inventing George Washington,” Edward G. Lengel, the editor-in-chief emeritus of the Papers of George Washington project at the University of Virginia, notes that Washington never spoke openly about his faith.

Lengel points out that our first president preferred to speak in terms of “providence,” rather than to make direct references to God, and that he believed his church attendance was part of his civic duty as a member of Virginia’s ruling elite. There is no evidence that Washington was an atheist, or even a deist, but he was certainly not an evangelical Christian in the modern sense.

The enduring popularity of the myths seeded by Weems over 200 years ago speaks to our relationship with Washington. Popular prints of the “The Prayer at Valley Forge” tell us more about ourselves than they do anything about Washington’s life. Washington is a mirror in which we see ourselves. If we are not careful, Washington’s memory becomes another victim of the unending culture wars. Believe that the United States is a “Christian nation?” Then, Washington accepted Jesus Christ as his personal savior. Want to legalize marijuana? Well, Washington grew hemp at Mount Vernon. (The last one is true, but George wasn’t smoking a bowl with the fibers cultivated on his plantation.)

Smash the mirror and who do we really see? The citizenship test approves four answers for Washington, all of which are true: “Father of Our Country,” first president of the United States, general of the Continental Army, and president of the Constitutional Convention. All these accomplishments, however, came after 1775 when Washington was already in his 40s.

If Weems was wrong about the guiding influence of Washington’s religiosity, what is his back story? How did he position himself to become, in the words of his great adversary King George III, “the greatest man in the world?”

To answer these questions, we need to acknowledge another truth in Washington’s life that is not among the approved answers in the citizenship test: He was a slaveholder. The importance of this fact is not that we are anachronistically applying 21st-century values to condemn an 18th-century man. Rather, it is to recognize that slaveholding was an essential prerequisite for Washington’s membership among Virginia’s governing elite that made his later fame possible.

Washington was a fourth-generation American whose family had established a modest tobacco plantation in Westmoreland County in Virginia’s Northern Neck. Slavery was becoming more, not less, important in mid-18th-century Virginia. Planters needed to expand their operations to survive the boom-and-bust cycle of the tobacco business. George inherited 10 enslaved people from his father’s estate in 1743. He died holding 123 humans in bondage. Washington sometimes mused on the injustice of slavery, but he also relentlessly pursued runaway slaves from Mount Vernon. Unlike other slaveholding founders like Thomas Jefferson, Washington’s will provided for the emancipation of all the enslaved people that he owned on the death of his wife. Most of the enslaved community at Mount Vernon, however, belonged to Martha’s dowry, and they became the property of her children with her first husband when she died in 1802.

It was no surprise that Washington led a life of public service. The Washington family had a strong tradition of leadership in Westmoreland County, made possible by the social capital they had accumulated over generations of plantation slavery. But Washington was not content to be a mere country squire; he sought martial glory.

The teenage Washington tried to persuade his mother to allow him to go to sea with the Royal Navy, but she refused. Although only in his early 20s, Washington’s social prominence in Virginia secured him a commission and shortly command of the Virginia Regiment. In 1754, Gov. Robert Dinwiddie dispatched him to confront French forces at Fort Duquesne (near present-day Pittsburgh), who opposed Virginia’s territorial claims in the Ohio River Valley. Washington’s errand into the Pennsylvania wilderness inadvertently sparked a global conflict, which was known in Europe as the Seven Years’ War.

His extensive wartime experience in the 1750s meant he was the obvious choice to lead the Continental Army in 1775. In turn, Washington’s leadership during the War of Independence set the scene for his postwar political career, serving as president of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, before being elected the first president of the United States of America in 1788.

Lawrence Hatter is Associate Professor & Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of History at Washington State University in Pullman.

This article is part of a Spokesman Review partnership with the Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service at WSU.