Church of Scientology is on opposite ends of two celebrity rape cases in LA, New York

NEW YORK — In a Manhattan courtroom, defense attorneys suggested the Church of Scientology fabricated rape allegations to tar an Oscar-winning former member’s reputation.

In a courtroom in Los Angeles, prosecutors contend the same controversial religion worked to suppress rape allegations in order to protect a celebrity member.

The trials of “That ‘70s Show” actor Danny Masterson and “Million Dollar Baby” director Paul Haggis on either coast have thrust Scientology — not a party to either case — into the spotlight, leaving the church embroiled in allegations it conspired to sink one man’s reputation over his treatment of women while protecting another from rape claims.

For nearly a month, Masterson has been on trial in Los Angeles, facing claims from three former Scientologists who say he plied them with alcohol and raped them — sometimes while they drifted in and out of consciousness. Deputy District Attorney Reinhold Mueller argued at the trial that the women feared “consequences that would come down from the … Church of Scientology” if they reported the rapes to law enforcement.

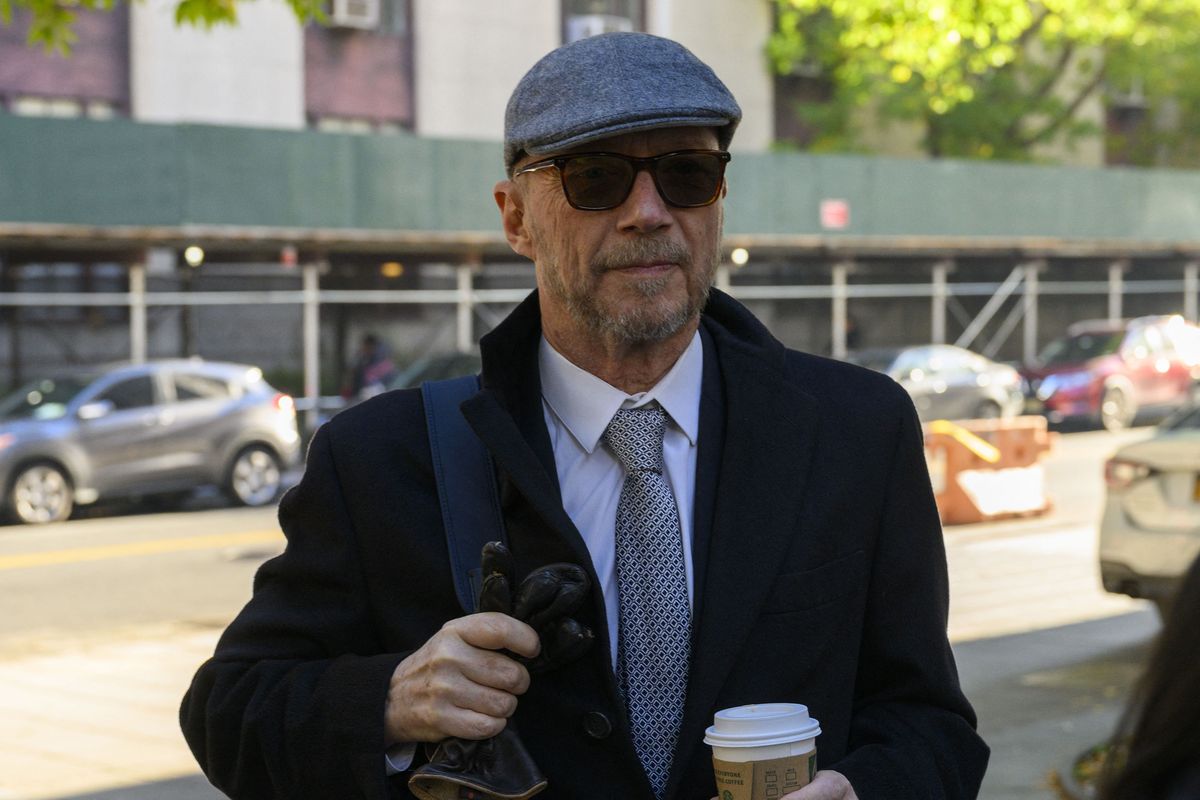

In New York, Haggis claimed the rape allegation he faces was ginned up by the church to destroy his reputation at the height of the #MeToo movement. Haggis, a former Scientologist, has not been able prove the woman accusing him of sexual assault is connected to the church in any way. The alleged victim’s lawyer and the Church of Scientology have adamantly denied any connection. Four other women accusing him of sexual assault, who are not plaintiffs in the lawsuit, testified during the trial against Haggis. He was also arrested in Italy on sexual assault charges, though the case was dropped.

On Thursday, Haggis was found liable of sexual assault under a New York civil law and ordered to pay $7.5 million in damages. Haggis said he will continue to “fight to clear my name.”

This may have been the first time the religion has been implicated in two jury trials at once, said Mike Rinder, a former executive with the church.

“It’s a very significant moment for the Church of Scientology,” he said. “Both trials obviously have Scientology very intertwined … to what is being put before the juries in New York and Los Angeles.”

Though the amount of evidence varies, lawyers in both cases cited Scientology when addressing otherwise thorny issues in their cases. For Los Angeles prosecutors, the alleged victims in the Masterson case said they feared retaliation from the church, which explains their hesitance to come forward. Haggis’ defense claims that church officials conjured up the rape allegations because they hate him and want to ruin his reputation.

Responding to the allegations, representatives for the church claim that Haggis has used his skills as a screenwriter to fabricate stories and lies about the religion and that Rinder and actress Leah Remini, who testified on Haggis’ behalf, “have no credibility” and make up lies about the church for money.

“The church has nothing to do with the claims against Haggis nor do we have any relation to the plaintiff, to the other accusers or to the attorneys who litigated the case,” said Karin Pouw in a statement to The Times. “The testimony of Haggis, Remini, Rinder and the other witnesses regarding the church was false in every respect. The church does not engage in any of the alleged conduct falsely testified to at the trial.”

Pouw added that Haggis admitted on the stand “what an arrogant bastard he is.”

Haggis hoped Scientology’s practice of “fair game,” in which church officials allegedly attack the reputations of perceived critics, might help him convince jurors that the sexual assault allegation was part of a concocted campaign, even if there is no proof, said Stephen Kent, a sociology professor at the University of Alberta who has studied Scientology and cults.

“A person could engage in disreputable activity and try to cloak it by claiming it didn’t happen, that the allegations are part of a Scientology conspiracy, when in fact the behavior actually occurred,” Kent said.

Rinder, the former church executive, testified in Haggis’ defense last week, outlining how “fair game” works, and how he conducted it when he worked for the church.

Lawyers for Haggis pointed in the trial to evidence of a decade-old campaign by the church to smear their client.

One woman testified that shortly after Haggis left the church in 2009, former Scientology chief spokesman Tommy Davis asked her to break into his Screen Actors Guild file to try to dig up dirt on Haggis.

“Scientology is permanently attached to [Haggis] like a dark shadow,” said Priya Chaudhry, Haggis’ attorney, in closing arguments Wednesday.

At trial, Haggis called upon well-known former Scientologists such as Rinder and Remini — along with his ex-wife and his daughter — to speak about the church’s alleged tactics.

“Men and women who have been raped absolutely deserve justice, but in this case, it’s absolutely Paul who is the victim here,” Remini testified Monday.

Attorneys for the woman accusing Haggis argued that Scientology was nothing but a sideshow from the actual claims in the case.

“The church is a cult and Mr. Haggis is a rapist. Both are true,” said Ilann Maazel, the woman’s attorney during closing arguments.

Not all former members side with Haggis, either.

“I can’t help but be super disgusted by how Mike Rinder and Paul Haggis have completely erased and harassed this woman,” Carmen Llywelyn, an actress and former Scientologist, said in a message to The Times. “They won’t listen to her that she isn’t involved with the church.”

The allegations of the church’s involvement are more prominent in the Masterson case.

Two of the women testifying allege they did not immediately report their rapes to law enforcement out of fear of being labeled a “suppressive person” by the church, which would probably result in their being expelled. Prosecutors have used the women’s fears of Scientology to explain why they took so long to go to police.

The women also filed a lawsuit against the church, claiming it a targeted campaign of harassment and stalking after they reported Masterson to law enforcement in 2016.

“I was a Scientologist, and Mr. Masterson is a Scientologist, and you cannot report another Scientologist in good standing to the authorities,” one of Masterson’s alleged victims said in court.

The church denied pressuring any women not to report Masterson.

“The church does not discourage anyone from reporting any alleged crime nor tell anyone not to report any alleged criminal conduct,” Pouw said. “The church has no policy prohibiting or discouraging members from reporting criminal conduct of Scientologists, or of anyone, to law enforcement. Quite the opposite. Church policy explicitly demands Scientologists abide by all laws of the land.”

Unlike the trials of Masterson and Haggis, the upcoming civil case against Scientology filed by Masterson’s alleged victims will place the religion at front and center, since the church is the named defendant.

The church denies stalking or harassing the women and says Remini is behind those allegations.

“There is not a shred of evidence to support plaintiffs’ claims of harassment,” Pouw said. “That case is nothing more than an attempted shakedown. … It is the church that is being harassed.”

Rinder said he hopes that the trial, which is on pause until Masterson’s criminal case is over, will expose even more of the church’s tactics.

“The allegations in the civil case are far more broad and far-reaching into the pattern and practices of Scientology and that stuff is going to all come out,” he said. “It will be hugely damaging to Scientology.”