‘We worked hard for that record’: The worst team in NBA history doesn’t want to be forgotten

The greatest championship teams often speak of things like fate and destiny, suggesting their immortality was preordained. But it isn’t only the winners who feel that way.

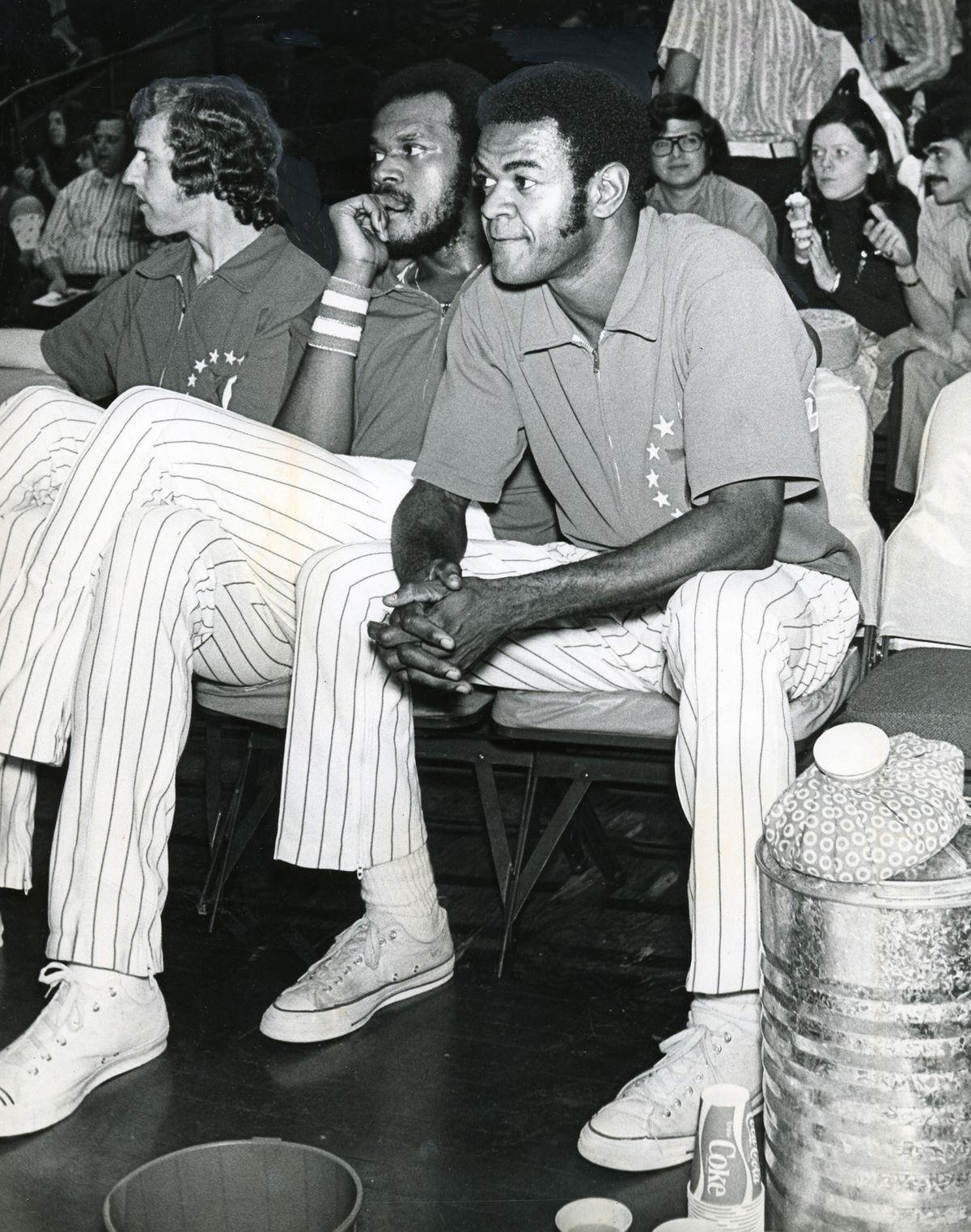

On Jan. 30, 1973, the worst team in NBA history had a chance to steal a win on the road against the Buffalo Braves. The Philadelphia 76ers – who entered with a record of 4-49 – had their best player, guard Fred Carter, at the free-throw line, down one point, with 1 second left.

“But I think some things are written in the wind,” Carter said in a recent telephone interview, more than a half-century later. “I was supposed to miss those free throws, and I obliged.”

That night, the 76ers lost their 12th straight game. The streak eventually hit 20, dropping them to 4-58 before they finally won again, over Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and the first-place Milwaukee Bucks on Valentine’s Day.

Philadelphia finished the 1972-73 season 9-73 – a .110 winning percentage that is the lowest in NBA history for a full season. (The Charlotte Bobcats were a smidgen lower at .106 after finishing 7-59 in the lockout-shortened 2011-12 season.)

That Philadelphia season changed careers, altered franchises and upended legacies. It also made history, which is why Carter doesn’t want any NBA team to break the mark for underperformance.

“Oh hell, no! We worked hard for that record. It’s like the Dolphins being undefeated,” he said, referring to the Miami Dolphins team that had a perfect record that same winter, capped by a Super Bowl victory in January 1973. “There are different ways you can earn immortality – and that’s our immortality; we earned it. It’s better to be remembered than not remembered at all. And if somebody breaks the record and has only eight wins, we will be pushed aside and forgotten.”

A ‘cry for help’

The 76ers were a team on the descent entering that fateful season, but no one could have anticipated just how steeply they would fall. The previous season, under Jack Ramsay, they finished 30-52, good for third place in the four-team Atlantic Division. The year before that, they were 47-35. In 1967, they had won the NBA Finals.

But a 1968 trade of franchise icon Wilt Chamberlain to the Los Angeles Lakers and a string of bad drafts changed the direction of the team. Before their record-breaking 1972-73 season, Ramsay quit to take over as coach of the Braves, and the Sixers took an unusual approach to finding a successor: They advertised the opening in the Philadelphia Inquirer, which the newspaper later dubbed a “cry for help.”

The team ended up hiring Long Island University basketball coach Roy Rubin after getting a recommendation from a former college basketball player named Jules Love, a friend of the 76ers’ owner.

Rubin had helped revive the LIU program, leading it to the nation’s No. 1 ranking among small colleges in 1968. But he had no NBA or even big-time college coaching experience, and the 76ers job would be a colossal challenge for even an accomplished NBA coach.

As the New York Times observed when the team announced Rubin as its new coach in June 1972: “Rubin’s plight with the 76ers may be best described by a recent Broadway show of which he was one of the financial backers, ‘Tough to Get Help,’ directed by Carl Reiner. It opened and closed in one night to poor reviews. The 76ers have been playing to poor reviews and heading downhill since they traded Wilt Chamberlain to the Los Angeles Lakers in 1968.”

On that show’s playbill, Rubin was listed as an associate producer.

Philadelphia put a surprising amount of faith in the unproven Rubin, signing him to a three-year, $300,000 contract (more than $2.1 million in today’s dollars).

“Who knows?” Rubin said at his introductory news conference, according to the Inquirer. “Maybe two weeks after the season starts, I’ll feel like killing myself.”

Rubin got the gig after a host of other coaches turned it down, including Al McGuire of Marquette. Team owner Irv Kosloff, the Inquirer reported, admitted that Rubin “isn’t exactly a household name. He’s no Al McGuire. Or any McGuire for that matter.”

Carter said it soon became clear to the players that Rubin wasn’t ready for prime time.

“We had a preseason game and we beat the Celtics, and he was full of joy, jumping up and down,” Carter said. “He told us, ‘I told you guys, if we can beat the Celtics, we can beat anybody.’ ” (The Celtics had come in first in the Atlantic Division the previous year.)

Carter said he and teammate Kevin Loughery – who had been traded together to the Sixers from the Baltimore Bullets the previous year – exchanged knowing looks and shook their heads.

“He didn’t understand that the Celtics took out all of their starters,” Carter said. “It was a preseason game. It wasn’t about a ‘W’ or an ‘L.’ ”

‘I feel sorry for them’

Philadelphia lost its first four regular-season games, but the Sixers were competitive, with each game decided by eight points or fewer. Then the bottom fell out, and the blowouts began. On Nov. 10, they lost their 15th straight game, a 125-106 Friday night home drubbing to the New York Knicks. That tied a record for consecutive losses to start a season.

Asked if the team, which was booed during introductions, might benefit from an upcoming six-game road trip, Rubin replied: “The only thing that’s going to help this team is to win a game. Tonight we made too many mistakes against a great team and a great coach. I can’t think of anything funny to say the way coach Bill Fitch of Cleveland did when he was going through the same sort of thing two seasons ago. All I know is I’m 15 games in the hole.”

But the Sixers did get a temporary reprieve on the road, beating the Houston Rockets 114-112 for their first victory. Aware that some Philly writers had stopped traveling with the team, Rubin called Philadelphia Inquirer sports columnist Frank Dolson. As Dolson recounted in his 1981 book, “The Philadelphia Story: A City of Winners,” Rubin identified himself as “Roy,” and Dolson replied, “Roy who?”

“Roy Rubin (pause). Of the 76ers,” Rubin said, then informed Dolson of the victory. “I figured you’d probably have some questions you’d want to ask me. So go ahead. Shoot.”

Dolson: “Well, there is one thing.”

Rubin: “Yeah, yeah, what’s that?”

Dolson: “Do you have any idea what time it is?”

The winning streak ended at one; the Sixers lost the remaining five games of the road trip. In their homecoming, they lost to the Portland Trail Blazers on Thanksgiving weekend to fall to 1-21. After beating the Braves, they hosted the Knicks again Nov. 29, and it was even a bigger dud than the first time as New York won 139-91.

“I feel sorry for them,” said Knicks forward Dave DeBusschere, who scored 20 points in 29 minutes.

Knicks coach Red Holzman emptied his bench but couldn’t stop the onslaught.

“I like to win easily, sure, but I don’t enjoy winning like that,” he said. “I just wish I could have a choice in the matter. The ball was just going in for us. That’s all.”

“I didn’t even feel like I was playing in a game. I feel so good I could go on the town when I get back to New York,” Knicks guard Walt Frazier said.

As the losing continued, others expressed empathy for the Sixers, too. The Times called them “last in their league but warmly regarded by compassionate men.”

“We were once called the universal health spa of the NBA because we got teams well,” said Carter, who led the team in scoring at 20 points per game. “We went into their town (and) they were on a losing streak; when we left, they were on a winning streak – because everybody beat us. Nine and 73 is misery after misery after misery.”

He recalled turning his travel bag around so people wouldn’t see the 76ers logo because he got tired of questions and comments like, “When are you guys going to win?” or “I feel sorry for you guys” or “You guys are a bad team.”

But the players’ morale was good, Carter said.

“We didn’t blame each other,” he said. “There was no finger pointing. Because we knew, individually and collectively, that we were not good enough to sustain ourselves to win games in the NBA. We were all probably pretty good role players that could help a team win. We didn’t have a starter that could carry us.”

After their blowout loss to the Knicks, Philadelphia won just one more game in 1972 before starting a 14-game losing streak that bled into 1973. They scored a season-low 79 points in a 32-point loss to the Golden State Warriors on Jan. 6 to drop their record to 3-38.

Somehow, Rubin still had the coaching job, although the critics rained down.

“Why can’t someone else take some of the blame?” he griped to Sports Illustrated. “I’m not the one who misses the shots, who throws the ball away, who won’t box out. They’re killing me. They’re trying to take my livelihood away from me.”

The players were equally contemptuous of their rookie coach.

“They criticize him for sloppy practices, lack of discipline and his failure to speak meaningfully during timeouts, at halftime and at postgame meetings,” SI reported. “More than his coaching, however, they criticize his personality.”

But Carter said it was unfair to blame Rubin.

“It wasn’t his fault – he wasn’t ready for that,” Carter said. “Anybody would take an NBA job if it was handed to them. It’s a shame. He took a job he wasn’t capable of doing.”

The 76ers finally fired Rubin on Jan. 23, after the team lost its ninth straight game to fall to 4-47. The deposed coach told the Times he had lost 45 pounds during the stressful season.

“I’m hurting pretty good,” said Rubin, who had turned 47 the previous month. “Most of my hurts are from embarrassment. I’m not in the greatest mental shape. It’s going to take a long time for this wound to heal. I guess it always does when you have been fired for the first time. Some nights when we got beat and the losses mounted, my stomach became one big knot. I felt so humiliated I could dig a hole and go through the floor.”

Rubin added that “I never promised I would be God’s gift to basketball in Philadelphia. I made it clear to the owner that I was moving into a situation where the hope for the season would be zero.”

Loughery took over as player-coach. The team lost its first 11 games after the switch – including the Jan. 30 loss in which Carter missed two free throws with 1 second left. After that game, Loughery, whose nickname was “Murph,” asked Carter if he had been tired.

“No, Murph,” Carter replied. “I just choked.”

After the 0-11 start under Loughery, the Sixers put together their only good stretch of basketball.

They won five of seven before returning to form, ending the season with 13 straight losses. Loughery’s record was 5-26, a .161 winning percentage.

Carter was named the team MVP, which he still doesn’t quite know what to make of.

“Did I lead us to nine wins, or did I lead us to 73 losses?” he asked.

From the NBA to IHOP

The Sixers did benefit from the disastrous season by getting the first pick in the 1973 draft, which yielded Doug Collins. Over the next few years, they fortified their roster by acquiring American Basketball Association stars Julius Erving and George McGinnis. By the 1976-77 season, they made it to the NBA Finals, falling to Bill Walton and the Portland Trail Blazers in six.

After the 1972-73 season, Loughery switched to the ABA, where he led the New York Nets to the championship in his first year as coach, and later coached several other NBA teams. But Rubin’s half-season proved to be a death knell to his coaching career. He never got another NBA gig, saddling him with a lifetime .078 winning percentage.

“It’s a shame because it ruined his coaching career – for a one-year stint coaching the NBA,” Carter said. “I’m sorry he couldn’t get another coaching job. He should not have been judged by that.”

Rubin later moved to Florida and ran an IHOP franchise, taught middle school and worked with at-risk kids. He died in 2013 at 87.

Years before his stinging sole season, Rubin made a comment that prophesied his own fall. Edward Hershey, who covered LIU for the campus paper before becoming a Newsday reporter, recalled that one night in Sunbury, Pennsylvania, they ran into Red Holzman.

As Hershey wrote in a retrospective piece for the Times: “This was well before Holzman’s championship run with the Knicks; he was a lowly scout in a remote town on a Saturday night. Rubin glanced back after they parted and shook his head. ‘Red’s one of the good guys,’ he said, ‘but he was an NBA coach and look where he is now. The pro game can eat you alive.’ ”

Frederic J. Frommer, a writer and sports historian, is the author of several books, including “You Gotta Have Heart: Washington Baseball from Walter Johnson to the 2019 World Series Champion Nationals.”