Boise mall shooter’s home was riddled with bullets. How did neighbors, police not notice?

BOISE – Police reports noted dozens of spent shell casings inside and outside Jacob Bergquist’s residence, as well as a homemade firearm silencer.

As soon as police approached the residence of the man who carried out the Boise Towne Square Mall shooting, they saw evidence that bullets had been fired there too.

In a Boise Police Department report released last fall, officials said they found spent casings outside the mobile home of Jacob Bergquist, who died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head after opening fire at the mall.

One officer noted “several spent .22-caliber casings” and said the “rounds appeared as if someone had been shooting in the side yard.” Bullet holes were also discovered in the walls and furniture of the Boise Bench residence, where he’d lived for approximately six months.

Bergquist shot and killed mall security guard Jo Acker outside of Macy’s on Oct. 25, 2021. He continued to fire bullets as he entered the store, killing Roberto Padilla Arguelles, who was shopping for gifts for his family. Several others were injured as Bergquist left the mall, fleeing north on foot and firing at Boise police officers arriving at the scene.

Bergquist, a vocal gun rights advocate and convicted felon, had drawn concern from local law enforcement. Federal officials after the shooting said he should not have been able to legally possess firearms. More than a year after the shooting, questions remain about how he was able to discharge a firearm numerous times in a residential area without attracting the attention of neighbors or police.

Bullets fired inside shooter’s residence

Boise police Officer Dennis Herron took photos at Bergquist’s Fry Street mobile home the day after the shooting. In his report, he detailed several spent .22 casings “strewn all around the ground near the stairs” of the residence. Like another officer, whose name was redacted from the report, Herron wrote that it appeared the bullets had been fired at that location.

When he entered the residence, Herron noted even more spent rounds of ammunition, though he didn’t describe what caliber they were.

“The couch and some of the living room walls had what appeared to be bullet holes in them,” Herron wrote.

As he walked down the hallway of the residence, he saw a small orange steel shooting target on the floor near the bathroom. The target had been placed in front of a foot stool, coffee maker box and a piece of plywood framing, and several bullet holes appeared in the walls and frame of an exterior back door. Bergquist seemed to use the plywood as “a small backstop or barricade” for shooting, Herron wrote.

Police didn’t say how many bullet holes they found inside the residence, but an evidence roster in the report noted what appeared to be more than 100 miscellaneous ammo casings found in Bergquist’s living room. The unnamed officer’s report noted “a large number” of bullet holes in the apparent backstop that Herron described. That officer described the bullet impacts as the result of a .22-caliber firearm.

“Based on the location of the couch, the bullet strikes to the living room wall corner, spent casing and the location of the target/backstop are consistent with someone (Bergquist) sitting on the couch and target practice shooting,” the officer wrote.

Herron also reported finding a plastic soda bottle containing what looked like .22-caliber ammunition in a trash can inside the home.

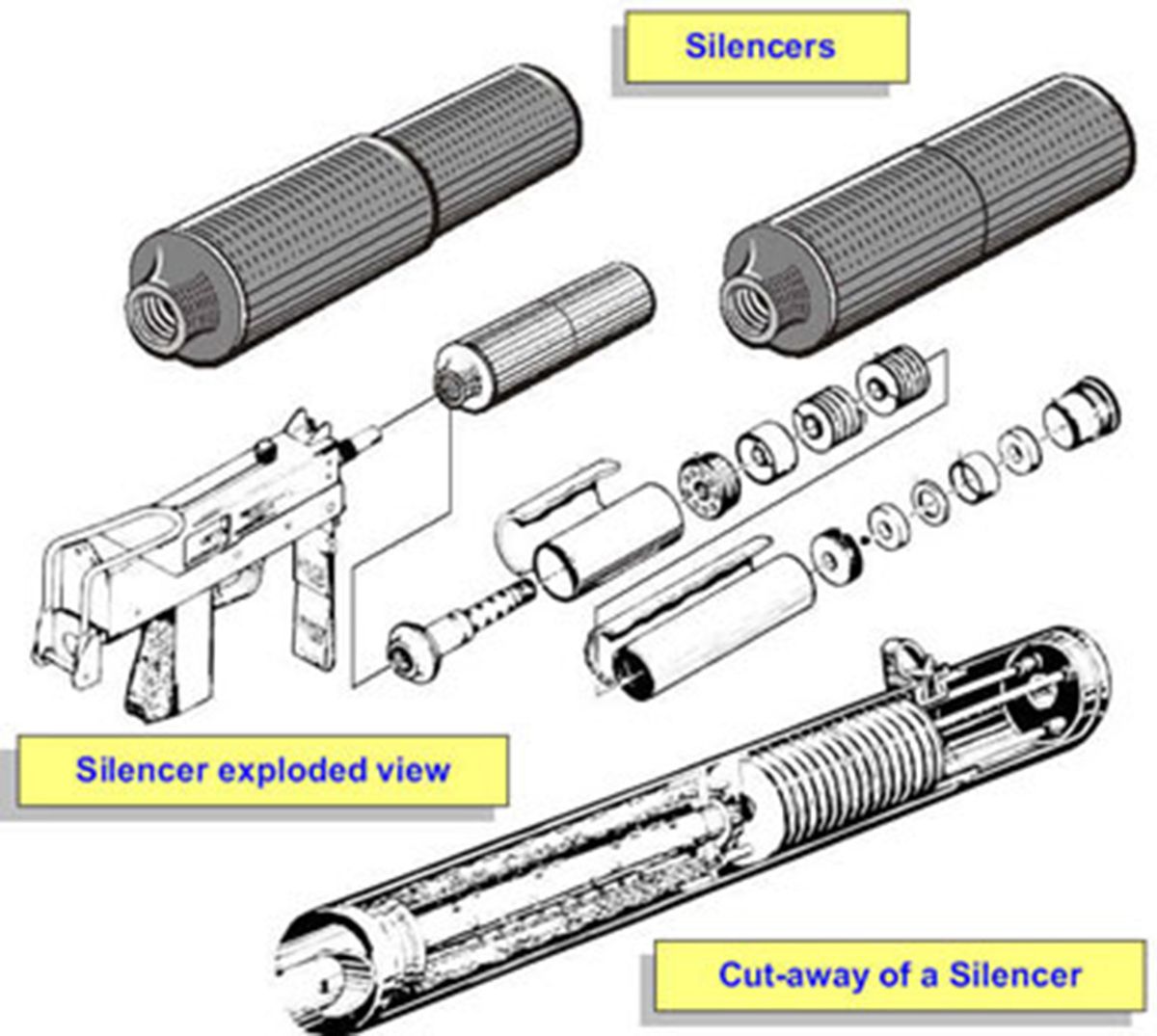

In addition to the spent rounds, officials found a homemade firearm suppressor, also known as a silencer. While commercial suppressors are available, they’re sometimes illegally manufactured out of items like fuel filters, plastic bottles and oil filters, said Jason Chudy, spokesperson for the Seattle Field Division of Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

Suppressors attach to the barrel of a weapon and reduce the noise made when gunpowder ignites and expels a bullet. According to the American Suppressor Association, suppressors trap and disrupt the gases created in that explosion, dispelling them more quietly.

“(The term) ‘silencer’ is kind of a misnomer because it really doesn’t silence the gunshot,” Chudy told the Idaho Statesman in an interview.

How would a suppressor impact noise?

The Statesman requested public records for any noise complaints or reports of shots fired in the mobile home park when Bergquist lived there. According to the Boise Police Department, it has no records of such complaints.

The department declined to comment further on the shell casings, bullet holes and shots fired at Bergquist’s home without detection.

“The details in the report are a documentation of the facts that exist and what is available about this investigation,” department spokesperson Haley Williams told the Statesman in an email.

The Statesman has also reached out to Fairview Village, which owns the mobile home park, to ask whether residents reported any shots fired. Boise police interviewed several of Bergquist’s neighbors in the days following the mall shooting. None of those neighbors reported hearing the sound of gunshots from Bergquist’s residence.

It’s unclear what weapon Bergquist may have fired at his mobile home. Police reported finding a loaded “American Arms .22” – which may refer to a North American Arms mini revolver – in Bergquist’s kitchen, and Bergquist had posted videos online of himself at a Boise shooting range firing a .22-caliber Beretta Bobcat, which the manufacturer describes as a “pocket pistol.”

Employees at the shooting range told police Bergquist had visited several times, including nearly daily trips in the weeks preceding the mall shooting. They said he’d spoken with employees about how a suppressor would affect his .22.

According to American Shooting Journal, .22-caliber firearms are typically quieter than 9 mm firearms, which are more common. The type of ammunition fired and the surroundings can also impact a firearm’s sound. Still, a .22-caliber pistol gunshot is around 140 decibels – about the volume of a firecracker and capable of causing pain and hearing loss, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

One National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health study found that professionally manufactured suppressors can reduce gunshot noise by 17 to 24 decibels, bringing a .22-caliber gunshot to roughly the same volume as standing near sirens or someone shouting near your ear.

Chudy said homemade devices – like the black aluminum one found under Bergquist’s front steps – would likely be less effective at reducing noise, so it’s unclear how it may have affected the sound of gunfire. A muffled or distorted noise may have obfuscated the sound enough to avoid drawing attention.

“People may know what a gunshot sounds like, but a muffled gunshot might sound different,” Chudy said.

Police said they didn’t find any bullets strike or impact locations outside of the mobile home, but those inside the residence indicated “several” hit the wall, door and door frame rather than the homemade backstop. Experts note that bullets can travel through walls and doors, creating a hazard for bystanders or neighbors.

Public records showed the mobile home park where Bergquist lived is a little larger than 3 acres, and satellite images showed several residences that appeared to be about 30 feet from each other. Bergquist’s mobile home was a single-wide trailer, which are typically about 18 feet wide and 80 feet long, manufacturers say.

According to hunter education experts, .22-caliber bullets can travel more than 1.5 miles.

Bergquist couldn’t legally own suppressors

After the fatal mall shooting, ATF determined Bergquist should not have owned any firearms since he had been convicted in Illinois of theft exceeding $300 – a felony that carries a potential sentence of more than one year. Local law enforcement had asked the bureau several times before the shooting whether Bergquist was legally allowed to possess firearms, the Statesman previously reported.

His felony conviction also would’ve precluded him from legally owning a firearm suppressor.

The devices have been regulated under the National Firearms Act since 1934. Anyone who purchases one must pay $200 and register with the ATF, which tracks the devices. In 2016, ATF reported 18,000 registered suppressors in Idaho. By 2021, that number had increased to nearly 41,000.

If Bergquist’s suppressor had been found before his death, he could’ve faced a fine of up to $10,000.

“When we do find people who’ve manufactured their own silencers or mufflers, we will take action,” Chudy said. “We prefer them to turn them over to us, but if not we can initiate criminal enforcement procedures against them.”

Bergquist didn’t use a suppressor during the mall shooting, for which he used a 9 mm Heckler and Koch VP9 pistol. Lindsay Nichols, federal policy director for the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, told the Statesman in an interview that a suppressor could have made the situation even more chaotic and deadly.

“If it’s not clear what the noise is, it’s not clear where it’s coming from, that can be dangerous,” Nichols said. “It takes away the ability for bystanders to identify and alert police if they don’t know what it is.”